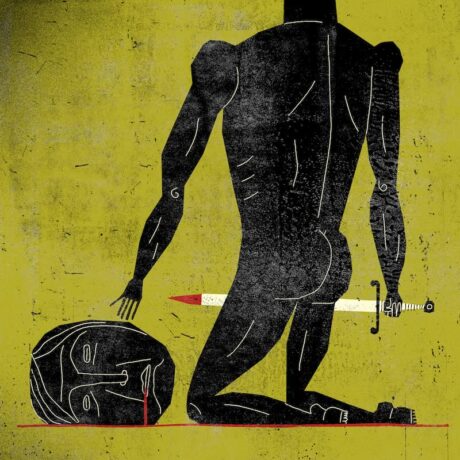

For IN Series Artistic Director Timothy Nelson, opening the new season with Alessandro Stradella’s St. John the Baptist next month isn’t just an artistic decision; it’s a long-held passion. With a bold new English libretto, a 1970s setting, and its first-ever full staging, Stradella’s explosive oratorio comes alive as a work of staggering musical invention and psychological complexity. The story retells the biblical account of John the Baptist’s final days as he’s caught in a dangerous triangle with the lustful Herod and the manipulative Salome, whose shocking demand for John’s head leads to a climactic act of violence. I had the pleasure of speaking with Nelson to hear his thoughts on why this rarely performed baroque masterpiece is the perfect piece for right now and how its themes of identity, repression, and forbidden desire hit harder than ever. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

What drew you to Alessandro Stradella’s St. John the Baptist as the IN Series season opener, and why now?

It’s a piece I’ve been wanting to do for almost 20 years. It’s a little-known piece, but there was a recording that was put out in the late eighties. The music is just astonishing — you can’t even believe that this music was written at all. And the storytelling is so novel, especially for the 17th century. The story of Salome, even though it’s really familiar, is not set very often, and it has an inherent drama and psychological complexity and sexual terror. We don’t think of baroque opera or Baroque theater as something that is so fraught and has so much inherent drama. So, between the music and the chance to do this really vivid story, I’ve always wanted to do the piece. Then, in doing a season of all premieres, I thought, how cool to open with actually the premiere of something that was written over 300 years ago?

You’ve said that Stradella’s version asks something “different” of us than Strauss’s Salome. What exactly is that difference, and how does your staging bring it out?

When we think of Oscar Wilde’s version, the thing we most think about is how shocking it was. The theater play was banned in Britain for 30 years after it was written. There were riots in Chicago when they tried to do the American premiere of it. It’s a piece that is shocking and salacious, even from the time it’s written. But this version, in a way that’s very similar, is equally as shocking musically and dramatically. It’s totally unique, and that’s not surprising coming from Stradella, because his life was shocking. He was shocking. The music he created, the art he created, and also his personal life. So in that way, it’s similar to the Strauss Oscar Wilde version, but that version focuses on Salome as the main character and as a character who has incredible psychological complexity and depth and changes over the course of the opera. Stradella’s version of Salome is important and gets amazing, fearsome, terrifying music — especially for the soprano having to sing it. It’s really about Herod, and Stradella hints at this past relationship between Herod and John. And Herod is sort of forced into killing this person that he clearly has a great affection for. So, in that way, it’s very different from the Oscar Wilde. It’s equally as crazed, equally as subversive, but it changes the focus.

Stradella’s opera was originally written as a concert work. What challenges or opportunities did that present when fully staging it for the first time?

It doesn’t present challenges in the way people would think because we think of oratorio as a concert form that is something more respectable and more spiritual and more tame than opera. But in fact, oratorio was invented in Rome because opera and theater were banned by the church in Rome. But it didn’t mean that the people who had power and money didn’t want to see opera or to see theater. It’s just they weren’t allowed to. So the only way they could experience drama or musical drama was to invent oratorio. But the pieces are no less dramatic. They’re no less sometimes scandalous. They chose stories from the Bible, but they chose very scandalous stories from the Bible. And so as a piece of music theater, it is equal in drama to the early operas that were being rented in Venice at the same time — maybe even more dramatic. Actually, I would find it hard as a conductor to make a concert piece out of it because you can’t believe it’s not meant to be staged. It is fast-paced, the characters are etched with remarkable psychological depth, and it’s very plot-driven. As a stage piece it’s very natural. There are some oratorios that would be more complicated and that maybe don’t have the same sort of dramatic momentum that this piece has. But this piece was very well suited to become a stage work. It’s hard to believe that no one had done it earlier, actually.

This production incorporates a new English text by Bari Biern. How did you collaborate with her on shaping the narrative and tone?

Bari is someone who’s had a relationship with our organization for many years, long before I came in 2018. But I think Bari had been writing translations for us, sometimes performing with us, and she used to write for Capital Steps, and won a Helen Hayes. During my tenure, she did our translation of Rigoletto last year. Bari is a brilliant rhymer and a brilliant comedian. This piece is not a comedy, but it has certain elements of absurdity and of grotesqueness, and I thought Bari would be really well suited. I wanted to give Bari a chance to do something that wasn’t silly and that was kind of dark and sometimes funny, but ultimately quite a tragedy.

However, rhyming was really important to the original piece, and by doing it in English, we needed someone who was really good at clever and smart rhyming. We’ve chosen to set this particular production in the 1970s because we’ve delved into this relationship between Herod and John. I wanted to find a place where a relationship between two men was at odds with the social norms — of heteronormative American suburbia of the 1970s. Putting it in the seventies gives an opportunity to the English translator to have fun with language, since the seventies were a time when the American language was really rich with unique words that we don’t use now. I thought Bari would have a good time digging into how language could fit with music, but particularly language from that period.

As both director and music director, how do you balance the visual storytelling with Stradella’s richly expressive score?

Obviously, the practice in opera is to have a separate conductor and director, which is very different from the way we think of theater. Even in music theater, there’s ultimately one person in charge in the room, the stage director. And there’s a hierarchy of the stage director and the music director. But in opera, they’re equal in the rehearsal room. So, trying to find someone who can do both is logistically a challenge. But I think it’s a much better way to make a piece of musical theater opera because there shouldn’t be a division between music and text and music and drama. The two are telling the same story, and they’re telling it together as one unified thing.

If you have one person or one creative mind that is shaping the music, the embodiment of that music in a way that is telling a unified dramatic story, to me, is a better way to get to a cohesive whole. It’s not possible when you get into romantic opera, where the orchestra parts are so complex and the size is so big and you have a chorus, but this is five singers and a baroque orchestra. It’s the sort of space where we can do this really unique experiment, and what it means to have just one artistic vision for the project.

Stradella’s music was admired by the likes of Handel and yet remains relatively obscure today. What do you think contemporary audiences will find most surprising about his music?

Handel, Bach…brilliant. Bach, especially, beyond words. Monteverdi, who is about a hundred years earlier than those guys, even a little more equally brilliant. People think of Stradella as a kind of a bridge between those poles — between Monteverdi and early opera and Handel. That’s really unfair to Stradella, who wasn’t just a byway between the two. Stradella was writing music that was wholly original, wholly his own, and super complex. His dissonances, his use of rhythms and syncopations, the way he etches character. One example: Salome, when she’s trying to cajole Herod and convince him to cut off John’s head. This young 13-year-old girl saying I want you to cut off the head of this man is a really gruesome idea. She does it in a way that is vocally pyrotechnic almost like Whitney Houston. It goes from the bottom to the top of the range, very fast, rageful, and crazy. That sets up an aria that is totally still and eerie and placid. So Stradella is the master of surprise — the master of doing the thing you’re not supposed to do. He was an outlaw and it comes out in the music.

Were there particular scenes or musical moments in St. John the Baptist that felt like breakthrough moments for you as a director?

The scene of Salome going between emotional poles to try and win her argument — and this argument is actually part of a larger scene in the second act — is all her trying to convince him to give her the head. And it’s a masterpiece of a character, psychology and music, and the shifting psychologies of people. The piece is famous also for its final duet because Salome is singing a very happy, joyful line, and her text is all about how she’s filled with elation and she doesn’t know why. And underneath, Herod is singing different music that is about how he senses impending doom. He’s so frightened and he doesn’t know why. And it ends suddenly just in the middle of the line and we know it’s the end because Stradella writes that’s the end of the oratorio. We assume that’s the moment the head gets cut off. That’s another moment that is really interesting to figure out how to embody as a director. The piece is full of those sorts of innovative moments.

You’ve led IN Series through productions that combine opera with other forms — from immersive theater to contemporary dance. What role does cross-disciplinary collaboration play in your creative process?

I love bringing together diverse artists, and by diverse I mean artists that are coming from different cultural expressive histories and working in different forms — forms that we would never think go together. Then we all get in a room and find a way to weave something that, again, makes the whole so much more than just the sum of the parts. So, for me, it’s very central in my practice, and it’s not just because I like working with people and collaboration is fun, but it’s really about a view of globalization, doing something positive for the world rather than what globalization actually costs the world. So bringing these voices together — which of course jazz is speaking to classical music and speaking to a whole economic and political history that was going on from the 19th and the 20th century — and having the arts openly having that conversation by putting those different things together and in dialogue with each other is really interesting and fun for me as an artist.

What has this production taught you about Stradella, about opera, or even about yourself?

In a way, it’s a homecoming. I wanted to do this piece for years, and as a harpsichordist and a baroque scholar of music, in a way, it’s my music. But I’ve never done Stradella before, and tend to do pieces that are optimistic and about joy. Even if that joy is found through grief and spiritual transformation. This is a piece that is gothic, gory, and dark, and there is some transcendent music in it. There is a beautiful message, especially in this production, about being true to the way God made you and not letting social pressure make you deny who you are. But ultimately, the story is very dark and almost so dark that it becomes satirical. That’s not the sort of work I do, so it’s fun to dip my toe in that space.

How has your time in DC influenced the kind of work you want to create?

I was overseas for about 15 years, and in opera, especially in classical music, we’re taught that Europe is the continent where we’re supposed to want to go and do work. That’s where there’s so much funding and where the productions are new and big in opera. And I was very early on in my time in Europe dissatisfied with being so far from the country that matters to me. Quite honestly, it was Trump’s first election that made me want to come back because I just felt it was wrong to be in the cheap seats. I wanted to be making work, even if it’s harder to make work in America, ’cause of the way the work is not funded. The work is somehow, at least to me, more important because it’s able to tap into real conversations that real people are having. And that, of course, is much more true now than it was eight years ago. Especially making work in DC feels like there’s the opportunity to do something that is relevant and will make a difference in people’s lives, whereas for me in Europe, I knew from day one that I was making work that felt easy, and I wanted to do stuff that felt hard.

What do you hope audiences walk away thinking or feeling after experiencing St. John the Baptist — especially those unfamiliar with Baroque opera?

The musician in me wants people to have a revelatory experience of not knowing this music and not knowing that this type of music existed, and that it could be so powerful, strange, and affecting. In a larger sense, this piece is so dramatically taut and so immediate and impactful that I want people to almost feel like they never thought opera could be so strong and so fast. I think people tend to think of opera as a space that can give these great, emotionally overwhelming moments. And between those moments, there’s a lot of waiting to get to the next moment, whereas theater tends to be something people think of as more immediate and compelling. I would hope people see this and realize that opera, when it’s done well and it’s the right piece, can actually be both at the same time.

Can you give a quick preview of what else is to come this season?

The next project in December, called The Delta King’s Blues, is kind of what was the germ for the whole idea of the season of premieres. It’s a work we’ve been spending the last three years commissioning. We have a resident artist program named the Cardwell Dawson Artist Fellowship — named for Mary Cardwell Dawson, who ran the National Negro Opera Company in DC in the forties. We started during the pandemic for local Black opera singers who wanted to explore some aspect beyond just singing — whether that’s composing, writing, or directing. And so this is the culmination of that with one of our artists, Jarrod Lee. He’s a librettist and he’s written with the composer Damien Geter a blues opera about the legend of Robert Johnson, the guitarist who sold his soul to the devil to learn the blues. So this is an opera that will combine a blues ensemble and a western classical ensemble and will be set in an immersive juke joint. And then in the spring, we’re doing a festival called Passion Plays, which are three works inspired by the medieval tradition of passion plays, but looking at contemporary themes. One is about police violence, police brutality, or political violence using the music of Bach. One is called Passio, which brings together eight female artists from around the world. It’ll include musical artists from Moroccan traditional Arabic music, Indian drumming, and more that all speak kind of a common language of improvisation. And we’ll talk about their experiences as women in this globalized society. And then the last piece is called For Women Serving Time, which is a new opera by Adrienne Torf about the experience of incarcerated women in America based on a poem by a scholar named Fatemeh Keshavarz. Our final piece is an opera I wrote about six years ago and never thought would be performed called Song of Sakuntala. It’s based on a 14th-century Indian play, and it brings together Indian classical music and western classical music and instruments into sort of a dance opera based on that play — which in the Indian tradition is sort of as ubiquitous as Hamlet is in the West.

Running Time: 75 minutes with Intermission.

St. John the Baptist plays October 2 to 5, 2025, presented by IN Series performing at 340 Maple Drive (IN Series’ new venue in Southwest, DC), and October 10 to 12, 2025, at the Baltimore Theatre Project (45 W Preston St, Baltimore, MD). Tickets range from $45 to $77 in DC and can be purchased online. Tickets range from $25 to $35 in Baltimore and can also be purchased online.