The Great Privation (How to flip ten cents into a dollar), written by Nia Akilah Robinson and directed by Mina Morita, tells a philosophical and profound story where memories cling to soil and roots, where what was buried begins to breathe again, and where the past has not vanished and has arrived in the present to begin a new chapter.

Two story timelines unfold in scenes that alternate between 1832 and 2025. Throughout the play, themes of scientific consent, racial justice, the impact of history across generations, and joy and triumph amid struggle emerge in powerful confrontations and confessions.

In 1832, a deadly cholera outbreak felled thousands in New York City. Neighboring Philadelphia didn’t escape its clutches; many Philly residents succumbed as well. Those unfortunate souls — if they were believers and well off enough — ended up buried in a church cemetery, here at Philadelphia’s African Baptist Church. This is the setting for the historical events in the play. When the curtain goes up, we meet a widow who is mourning the death of her husband alongside her teenage daughter. They also are protecting the body. They have to guard his burial plot from grave robbers, so-called “resurrectionists” who pillage the bodies of the poor, the Black, and the Black poor so that their bodies may be exploited for scientific study. (Historical information on this practice is in the digital program.)

Multiple scenes covering three critical days pit Mother and daughter Charity against graverobbers John and a janitor, who covet the deceased for dissection at Jefferson Medical College.

Almost two centuries later, in 2025, time has turned, but the earth remembers. And in its quiet and disquieting persistence, a new story takes root on the same Philly ground, now redeveloped as a summer camp. This is where we meet another mother-daughter pair who are spending the summer working there as camp counselors. Several scenes portray the contemporary history of Mother and her daughter Charity, and their present-day conflict. For instance, Charity “wants to know her history, to earn her Black stripes,” while her mother wants her to “stay out of the limelight.” Hard to do when Charity is one of three Black kids in her school.

Eventually, the two timelines encircle and echo each other in dramatic and surprising fashion. I won’t say more.

Gifted actors anchor us in the past and the present, all four brilliantly playing dual roles.

Yetunde Felix-Ukwu (Mother/Modern-Day Mother) and Victoria Omoregie (Charity/Modern-Day Charity) make a dynamic team. Are they really unrelated? Their chemistry, affection, and trust with one another made them instantly believable as mother and daughter in both timelines. Their “push/pull,” “give and take,” and “no/why not” were expertly performed.

Both are formidable in projecting bravery, strength, resolve, vulnerability, and love for one another, whether standing up to graverobbers or as co-camp counselors. Playwright Robinson has crafted a script that nails motherhood and daughterhood, and one that shows the character growing and changing as the play progresses.

Moreover, both are exceptional performers individually. Victoria Omoregie physically embodies a teenager in both eras and perfectly captures young adulthood sensibility and attitude appropriate for the timeline. She showcases a remarkable range. She made me laugh in both roles! Similarly, Yetunde Felix-Ukwu’s skill in conveying nuanced emotions while alternating dialects, body language, and tone back and forth from 1832 to 2025 and scene to scene is outstanding.

Marc Pierre (Janitor/Cuffee) shines while deepening the story’s moral complexity. As the 1832 janitor, he credibly argues the nobility of his graverobbing for science. “In the twentieth or twenty-first century, there will be no deaths from cholera!” His performance in that timeline forces the audience to see his complicity as nuanced, borne of inner conflict and self-preservation. Notably, Cuffee in the present, self-described as the “first Black queer supervisor at this white camp,” provides thematic connection to the 1832 janitor, showing that one’s story is not as black and white as it at first may seem.

Zack Powell (John/Modern-Day John) excels in both roles. As medical student/graverobber, he is coiled, steely, and cold as ice, but believably manic, silly, and rubber-limbed as camp counselor. Yet a core trait projected in both roles — which I’ll call white-male entitled privilege egotism — links both characters across time as if showing both sides of the same coin. His counselor salary is higher than his co-workers’. Naturally.

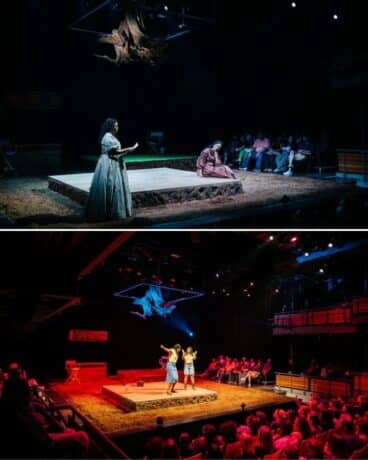

This production, led by Mina Morita, has crafted a stupendous show from front to back of house. The pacing is excellent; scenes flow fluidly and end with precise intention to keep the audience engaged. The spare set, dominated by a magnificent tree suspended from the ceiling, visually deepened the play’s meditation on time and the connection between past and present that it explored. The lighting design and sound design complemented the moods being evoked for each timeline.

My one quibble is that at close to two hours, the play is long without an intermission, and the ending fused with the after-show celebration on stage. But I wholeheartedly agree with the standing ovation for a triumphant premiere performance.

Go see The Great Privation (How to flip ten cents into a dollar). It’s stellar. It powerfully offers a mirror to our times today and captures the ways in which the ghosts of the past shape the present and won’t stay buried despite attempts to keep them hidden. And it also reminds us to find joy in adverse situations. To quote Alice Walker, “Hard times require furious dancing.”

Running Time: Approximately one hour and 45 minutes with no intermission.

The Great Privation (How to flip ten cents into a dollar) plays through October 12, 2025, presented by DC’s Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company and Boston’s Company One Theatre at Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company, 641 D St NW, Washington, DC. Tickets ($55 —$83, with discounts available and a limited number of PWYW tickets starting at $5 for every show) can be purchased online, by phone at 202-393-3939, by email (tickets@woollymammoth.net), or in person at the Sales Office at 641 D Street NW, Washington, DC (Tuesday–Friday, 12:00–6:00 p.m.). Discount tickets are also available on TodayTix.

The digital playbill is downloadable here.

COVID Safety: Masks are optional in all public spaces at Woolly Mammoth Theatre except for a mask-required performance Wednesday, September 24, 8 p.m. Woolly’s full safety policy is available here.

Connectivity Programming

In keeping with Woolly’s commitment to inclusiveness and broad community engagement, a range of connectivity programming augments multiple performances, including Community Conversations, Artist Talkbacks, Post-Show Discussions, a Call and Response Workshop, and Affinity Performances. Get there early or plan to stay after the performance to have time to engage with Woolly Mammoth’s “The Lobby Experience.”

The Great Privation (How to flip ten cents into a dollar)

By Nia Akilah Robinson

Directed by Mina Morita

CREATIVE TEAM

Scenic Designer: Meghan Raham

Lighting Designer: Amith Chandrashaker

Costume Designer: Brandee Mathies

Sound Designer: Nick Hernandez

Hair and Wig Designer: Lashawn Melton

Stage Manager: Sarah Chapin

Dramaturg: Sonia Fernandez

Dialect Coach: Bridget Jackson

Intimacy and Fight Director: Sierra Young

CAST

Mother/Modern-Day Mother: Yetunde Felix-Ukwu

Charity/Modern Day Charity: Victoria Omoregie

Janitor/Cuffee: Marc Pierre

John/Modern-Day John: Zack Powell