There’s something comforting in the fact that people 400 years ago dealt with many of the same problems we do. Opera Lafayette, a baroque opera company that performs in both Washington, DC, and New York City, presented a February 12th concert of 16th- and 17th-century European music and poetry all about love: love’s trials, love’s joys, and the in-betweens (including “my girlfriend won’t stop knitting,” which incriminated this reviewer).

The night’s festivities were held in St. Francis Hall, a Franciscan monastery, lovingly decorated with string lights galore and white-clothed cabaret tables with roses and chocolate snacks. Imagine a cabaret concert of 16th- and 17th-century music and poetry set in a monastery with free wine and chocolate to boot.

This was a one-night-only show for DC audiences, but New York–based audiences can catch the same show in Manhattan, February 14, at the Georgia Room on 23 Lexington Avenue at 7:30 PM, with cocktails provided by NY mixologist Alex Dominguez of Bar Calico.

The night’s programming included vocal duets, vocal solos, poetry, and instrumental numbers written by the likes of Henry Purcell (1659–1695), Joseph Haydn (1732–1809), Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643), and many more. The night’s offerings spanned English, French, and Italian, with all lyrics and translations available in programs provided to audience members. Providing translations for non-English operas in the United States is relatively standard, but having the lyrics available for the English-language pieces was a welcome addition. And from an accessibility perspective, I might add that my plus-one for the night is deaf and greatly appreciated the inclusion of both the translations and the less-common English lyrics.

Soprano Maya Kherani of the New York Philharmonic sang both explicitly female parts and single-speaker selections. Grammy-winning tenor James Reese sang male parts and others. Nicholas McGegan, described by The Independent as “one of the finest baroque conductors of his generation,” led the festivities as the host, harpsichordist, and curator. Part of McGegan’s hosting duties included reading the night’s poetry, which he did with relish. The instrumentalists included McGegan on the harpsichord, Natalie Kress as the first violinist, Rebecca Nelson as the second violinist, Alexa Haynes-Pilon on cello, and William Simms on the theorbo and guitar.

The modern costumes of Kherani and Reese, set against the sumptuously rustic venue of St. Francis Hall, resulted in a production that resembled a Shakespeare production set in the modern day. Another similarity to Shakespeare: while the musical offerings had the appearance of what we might call “high art,” the subject matter of ths chosen songs was frequently everyday challenges faced by lovers — including a poem featuring a man lamenting how his female lover’s dog was getting more of her attention than he, the aforementioned knitting joke, and a woman asking a man to confirm about 20 times in the span of three minutes that he loves her.

Some of the most theatrically interesting moments of the night were when a solo song or poem was not explicitly gendered, but was assigned to either Kherani or Reese, who each brought traditional femininity and masculinity to their excellent vocal performances throughout. We saw plenty of good old comedic male-vs.-female sparring, but also the authentic, heartfelt musings of each individual, which added depth and complexity to the evening’s comedy.

The performances were wonderful, with both leads and Natalie Kress’s technically excellent and expressive work with the first violin part and Rebecca Nelson’s with the second as prominent standouts. The diversity of the night’s offerings — vocals, instrumental numbers, and poetry — created a wonderful sampler for 16th- and 17th-century musings on love.

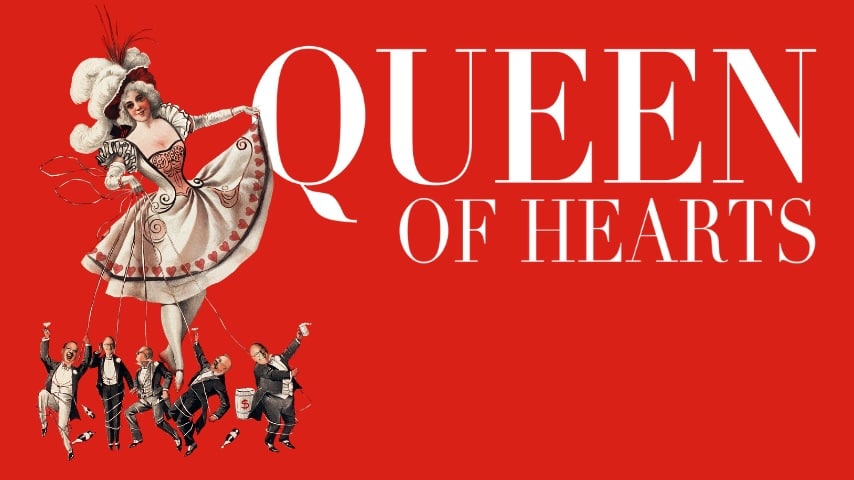

The only area of the event that left me with questions was the marketing: the online descriptions of the event stressed the evening’s bawdy elements. The poster art for the event — which features a woman from an illustration likely from the 18th century who has been edited to lead five tuxedoed, imbibing, rotund businessmen on leashes — invites audiences to expect some angles on love outside of arguably typical “man chases woman” theses, as well as more unexpected relationship-oriented subversiveness. In a show with over 20 numbers, only a few were overtly blue: the number “Oh that I had a fine man” performed with more overt sexuality by Kherani, and one moment where the two leads run backstage and a breathless Reese emerges with his tie and collar undone, and the most blue, the poem “Oh Mother, Roger with His Kisses” performed by Kherani. Otherwise, the night’s selections featured largely chaste romantic circumstances. We are reminded that in the 16th and 17th centuries, the only surviving artistic equivalents to a woman leading drunk men around on leashes would be scarce. In fairness, given the state of live theater in 2026, all bets are off on how you get people in the door.

In terms of atmosphere or audience behavior, the desired responses to the show’s subversiveness were, other than polite laughter, not nearly as present as elements of the marketing suggested or encouraged: Patrick Quigley, Opera Lafayette’s artistic director, has included a note in our programs saying that “applause, laughter, and the occasional good-natured jeer are not just allowed, they’re period-appropriate.” The night’s audience definitely treated the concert like a high-art, operatic showcase of top talent rather than the “sensual, humorous… amorous, cheeky, and bawdy” cabaret concert that some of the marketing suggested.

It’s unclear what they were specifically encouraging us, as audience members, to do, but if Opera Lafayette really does want to push for a more groundling-esque atmosphere, more explicit prodding may be necessary. But then again, the presence of not only a harpsichord but a theorbo alone may have prevented any hope of the audience treating the concert as anything less than the highest of “high art.”

Regardless, the programming was insistent on both its assertion that love’s intensity and tropes — some lofty, some low — are universal and its invitation to laugh heartily at ourselves, rosé in hand. In these anxious days, there’s a comfort in a reminder that much of what occupies our minds has been a tale as old as time.

Running Time: 75 minutes with a 15-minute intermission/

Queen of Hearts played February 12, 2026, presented by Opera Lafayette, performing at St. Francis Hall, 1340 Quincy Street NE, Washington, DC.

SEE ALSO:

Opera Lafayette announces 2025/26 season: ‘Drama Queen’ (news story, August 6, 2025)