Nell Gwynn (1650-1687) was not only one of the most talented actresses in Restoration Theatre, but also one of the most beloved. That was because “pretty, witty” Nell, as diarist Samuel Pepys called her, was an irresistible combination of comic invention, personal kindness, and unceasing good humor. She was a cherished mistress of the “Merry Monarch”, Charles II (1630-1685). Brought up in poverty, she went from being an orange seller and likely prostitute to one of the most idolized actresses of her time.

Charles II was restored to the English throne in 1660 after nine years in exile. He was known for his intelligence, unreliability, and love of entertainment. He subsidized two acting companies, the King’s Players, which he sponsored, and the Duke’s Players, sponsored by his brother James, then the Duke of York. Charles introduced actresses to the English stage after seeing them at the French court (female characters in England were played by men until the Restoration) and became the most powerful of Nell’s many admirers.

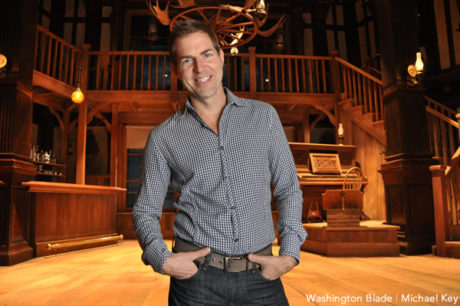

British playwright Jessica Swale has turned Nell’s story into a celebration of life in the theatre. Nell Gwynn premiered at Shakespeare’s Globe in 2015 and won the Laurence Olivier Award for Best New Comedy in 2016. Director Robert Richmond’s production is visually opulent, and, like the era it embodies, full of wicked fun.

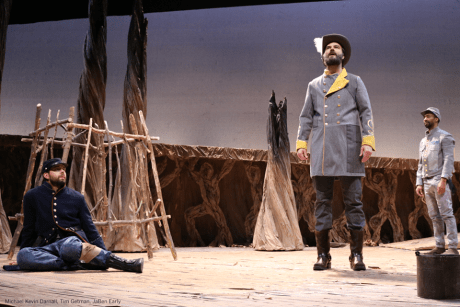

Nell’s first lessons in acting and love come from a prominent leading man of the King’s Players, Charles Hart. Alison Luff as Nell and Quinn Franzen as Hart share a sparkling chemistry and a knack for the somewhat flamboyant performance style of the era.

Nell is surrounded by a host of intriguing characters. There is the shyly appealing Ned Spigget (Alex Michell) whom Nell encourages when he is stricken by stage fright. There is Catherine Flye as Nancy, her dresser and confidante, who attempts to inject a note of reality into the proceedings. At times, recognizing that she is dealing with theatre people, she gives up completely.

Christopher Dinolfo is hilarious as Edward Kynaston, a rival diva who resents the intrusion of actual women onto the stage with their inartistic real figures and profound cultural ignorance. He throws a fit over his motivation during an entrance in which he has a single line. Theatre fans will not be surprised to learn that his inspiration derives from a long-ago childhood trauma.

Nigel Gore is pleasantly sympathetic as Thomas Killigrew, the beleaguered playhouse manager who must somehow maintain order in the chaotic world of Drury Lane. Michael Glenn offers a strange combination of neurosis and joy as the hapless playwright John Dryden. Hair festooned with feathers (or are they pens?), desperate for approval, he struggles to adapt to the advent of actresses and the many pressures of his role, financial and otherwise.

Inevitably, Nell’s background intrudes into her newly exalted existence. Her alcoholic mother (again, Catherine Flye) is on hand, comparing Nell unfavorably to the young ladies in the brother she runs. Nell’s sister Rose (Caitlin Cisco) bears the brunt of Ma Gwynn’s dysfunction.

Charles had numerous mistresses. Regina Aquino plays two of his favorites, Lady Castlemaine and Louise de Kéroualle. As the tempestuous Lady Castlemaine, Aquino excels in her scene with Charles’ much-neglected wife, Queen Catherine (Zoe Speas). The two have a magnificently zany catfight, conducted, in Catherine’s case, entirely in Portuguese.

Louise de Kéroualle, whom Charles called “Fubbs” was known for her beauty, her mercenary nature, and her baby face. Brought in by the French to fascinate the king, she remained in favor for many years. Luff’s Nell, a commoner, vanquishes her aristocratic rival on the stage: where else? Sporting a gigantic hat, she parodies La Kéroualle. to her face in fractured French. Playing to her king as well as the audience, Luff achieves a kind of lunatic charm which Nell herself would have appreciated.

Nell’s chief antagonist, Lord Arlington (Jeff Keogh) attempts to force her to give up Charles. But Charles and Nell have a deeper relationship than one might expect. Like Nell, Charles experienced adversity. His father, Charles I, was executed in 1649 at the height of the English Civil War. During the Commonwealth, after his father was overthrown, Charles suffered years of exile and privation. He traveled in disguise, with a price on his head. At one point he was reduced to hiding in an oak tree.

Predictably, Charles became cynical. But, like Nell, he was capable of kindness. The Penderel family were among the many persecuted Catholics who helped him in his time of need. When he became king, he offered them a pension and a full account of his adventures after he left them.

Charles was no slouch as a humorist, either. His friend, poet and voluptuary John Wilmot, 2d Earl of Rochester, wrote of him:

“We have a pretty witty king,

Whose word no man relies on;

He never said a foolish thing,

Nor ever did a wise one.”

R. J. Foster as Charles is suitably worldly, and somewhat preoccupied. But no one can doubt that despite the enormous power differential, he and Nell have a true romance.

If there is any justice in the world (Yes, I know) Mariah Anzaldo Hale’s costumes will receive a Helen Hayes nomination. As always with the Folger, the creative team; Kim Sherman (Original Music), Andrew F. Griffin (Lighting Design), Tony Cisek (Scenic Design), and Matt Otto (Sound Design) offer their very best. The highly skilled Musicians are Kevin Collins and Zoe Speas.

In a time when aristocracy was prized, Nell overcame her humble origins and blazed a trail which has made her famous centuries after her death. And she was a member of an aristocracy; the aristocracy of talent.

Don’t miss her inspiring, broadly comic story.

Running time: Two hours and 30 minutes, plus a 15-minute intermission.

Nell Gwynn plays through March 10 at The Folger Theater at 201 East Capitol Street SE, Washington, DC. For tickets call (202) 544-7077 or order online.