There are good reasons why Bruce Norris’ 2010 Pulitzer Prize-winning play Clybourne Park has been staged no less than five times in the past four years by local companies.First, it is a superbly crafted evening of theater, with complex characters and searing dialogue that is by turns funny, scathing, sad, delusional, and revelatory. Second, and equally important, it remains timely. The theme of social and racial inequality continues to resonate as our cities, and Washington, DC in particular, gentrify at a quickened rate.

The taut, two-act drama takes place in the same Chicago house over time yet its roots go deeper – recalling Lorraine Hansberry’s iconic A Raisin in the Sun. The first act takes place in 1959 as Bev and Russ, a middle class white couple, are packing up their tidy house and moving to suburbs two years after the tragic suicide of their beloved son, a Korean War veteran who is disgraced by war crimes.

The buyers, as it turns out half-way through the act, are the Younger family, Hansberry’s protagonists who seek to move to better their place in the world as the first ‘colored’ family to live in the neighborhood.

The second act reverses the action. Fifty years later, the now-derelict house is poised to go through yet another transition as well-to-do white millennials, in search of their own version of a better life, flee the suburbs for a shorter commute.They purchase the house and plan to replace it with an even bigger home on the site originally settled by their Scandinavian and German ancestors before African Americans bought into the neighborhood.

The George Washington University’s Department of Theater and Dance is the latest local troupe to restage Norris’ masterpiece, and they do a highly respectable job of it.

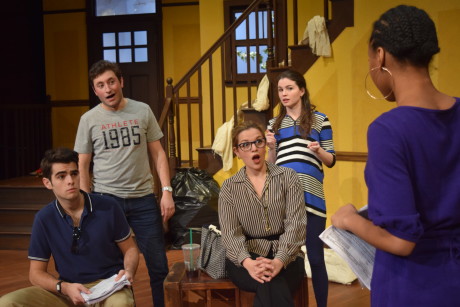

Key to the success of any Clybourne Park production is to use the same cast — convincingly — in different through cleverly related roles in the first and second acts. The agile young cast stand out here, demonstrating terrific success in inhabiting both their characters.

Josh Bierman has the most pivotal assignments, as he is the mouthpiece through which America’s most tortured views on race find expression. Bierman executes both Karl and Steve flawlessly, with a manic energy that bores wildly into our central, tragic myths of inequality.

Kait Haire’s (Betsy/Lindsey) characters are comically different. As Betsy, Karl’s nearly deaf wife, she sits by wide-eyed but intensely observant, while Lindsey, Steve’s spouse, is a chatterbox who rarely stops talking. The fact that both are pregnant provides parallel motives for Bierman’s intense characters. As both Karl and Steve, he seeks the best possible futures — through his own narrow lens — for his unborn children.

Chinelo Okpala (Francine/Lena) is also a standout , traversing 50 years from an obsequious housemaid who knows her place in a white world to a self-assured modern black woman who pushes back forcefully against Steve’s accusation of racism.

(Albert/Kevin) as Francine’s husband and Lena’s partner, nails his parts, first as the humble, well-mannered black man and then as an obviously successful black professional who is slow (but sure) to anger. Others are more effective in one role or another.

Samantha Gonzalez excels as Kathy and Tim Traversy as Tom, who try to keep negotiations on track during the second act while giving voice to their own views about neighborhoods and change.

Kent-Harris Repass is excellent as Russ, who, haunted by the death of his veteran son, fights against his own depression and anger. Jeremy Neff has a small but startling role as Kenneth, the young returned soldier. His body language, signalling his withdrawal from the world, is achingly real.

Alan Wade, in his 35th directorial assignment for the department, does an outstanding job of bringing this incisive play to life, coaxing out the parallels between the two acts in myriad ways.

In the first act, he moves his players around the stage deftly, constantly repositioning them into singles, dyads and triads that give visual meaning to their shifting alliances with one another. The second act, by contrast, is played mostly sitting down, as all the players haggle over what vaguely appears to be a sales contract. But as the dialog heats up, with true motives and beliefs revealed, the players get up, pace, and realign themselves, displaying much of the same behavior that their forebears demonstrated in the same house a half century before. Though both acts concern themselves chiefly with race relations, there is also PTSD to consider, along with a breath of anti-semitism and less-than-enlightened attitudes towards developmentally challenged individuals.

The silent character in this drama is of course the house itself. Molly Hall’s set design reveals a home with “good bones” even as it devolves from respectable to ragged, proud to frankly endangered. Kevin Small’s costumes, parallel their eras faithfully. Who can forget that 50s housewives accomplished their tasks in starched shirtwaist dresses and high heels, and when housemaids came to work better dressed than many women in the workplace would aspire to today. Gregg Jones’ lighting, particularly at the end of the play, gives vivid expression to the sad history that quite literally underlies the house.

One would hope that someday Bruce Norris’ brilliant play will be a period piece, well-wrought but clearly belonging to another era. Sadly, we are not even close. As neighborhoods shift at a breathtaking rate, and every step forward toward racial equality is countered with news-making episodes of enduring discrimination, this exquisite play will continue to hold audiences deep in its thrall.

Running time: Two hours and 10 minutes, with a 15-minute intermission.\\

Clybourne Park plays through February 21, 2016 at George Washington University’s Dorothy Betts Marvin Theatre – 800 21st Street, NW, in Washington, DC. For tickets, call the box office at (202) 994-0995, or purchase them online.

RATING: