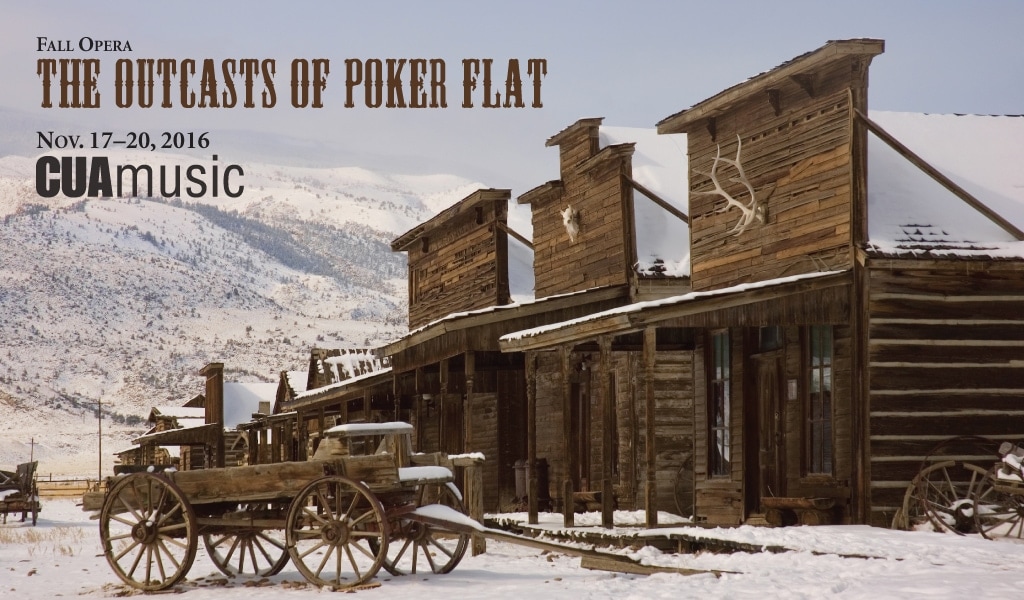

New opera: The Outcasts of Poker Flat at Catholic University

(Or, “Two Prostitutes, a Thief, and a Gambler Walk into a Bar…”)

This month, The Outcasts of Poker Flat, a 70-minute one-act chamber opera by Composer/Librettist Andrew Earle Simpson, directed by James Hampton, receives a fully-staged premiere of its chamber ensemble version by the Benjamin T. Rome School of Music at The Catholic University of America’s Ward Recital Hall.

Production Dates and Times:

Thursday, November 17th@7:30pm

Friday, November 18th@7:30pm

Saturday, November 19th@7:30pm

Sunday, November 20th@2:00pm

At Ward Recital Hall on the campus of The Catholic University of America.

PURCHASE YOUR TICKETS HERE.

Note that the Metro Red Line stop (Brookland/CUA) is closed for Safe Track, so alternative transportation is needed. There is free parking along Harewood Road, NE, next to the School of Music.

It will also feature newly-created video sequences by Chicago-based filmmaker Nicholas Ferrario.

Background

The Outcasts of Poker Flat is a short story by American author Bret Harte, first published in 1869 in the Overland Monthly. I adapted this story for my libretto, staying reasonably close to the curve of the story which Harte tells, with some adjustments. URL to read online.

The Outcasts’ Life Before 2016

My opera was first presented in scenes at the 2011 Kennedy Center Page to Stage Festival, then had a production at the 2012 Capital Fringe Festival, both with piano. This 2016 production represents the first performance of this new chamber ensemble arrangement. The ensemble, for six players, is:

Clarinet

Violin

Double Bass

Accordion

Percussion

Piano (actually, 2 upright pianos: one tuned, one specially detuned)

The Music

The score for Outcasts is diverse and distinctly American, drawing on contemporary classical style as well as American hymn and fugueing tunes, parlor songs, mountain fiddle music, and saloon songs. The music is tailored to serve the story at every point and help to define the milieu of 19th-century California.

The score is in 9 scenes with four “Snow interludes,” and has numerous set-piece arias, duets, and ensemble numbers.

I have specifically written for upright pianos and accordion, feeling that these present a more authentic and realistic sound-world for the characters on stage.

Preview audio clips, a synopsis (and video to follow) can be found here, and in the extended discussion below.

The Story

The scene is laid in California, November 1850. In fact, a specific date is given for the start of the tale: November 23rd, a Saturday morning. Poker Flat is a real place, nestled in the remote pine words at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, a remote locale even today. Nobody lives there now. But in 1850, Poker Flat was a thriving mining camp, a settlement for those who rushed to California to find gold, and who built shacks and shelters. Once the prospectors were there, the inevitable servicers followed to supply, feed, and entertain them. To Poker Flat came groceries and dry goods vendors, sellers of durable goods and supplies, clothing and outerware…then saloons…and, of course, prostitutes. Early in the story, Lori, the older whore, indignant at having been summarily cast out of Poker Flat, laments in the libretto that “we [meaning she and her co-worker Cassie] were the only thing to do in that town ‘cept gamble.”

The story of the West is that of an initial state of lawlessness, as prospectors flooded California in 1849 to grab as much as possible, hold onto it, and keep others from getting it. Over time, moneyed interests with high stakes in the cultivation of the region’s natural riches, as well as a typical social tendency towards “improvement” meant the introduction of laws and the supply of agents to enforce it. And this is why Westerns so often feature sheriffs and marshals against outlaws, after all: it is a confrontation between the lawless, “Wild” West and the new West of law and order.

Poker Flat was at that point of development whereby civilizing influences were at work, although sworn law enforcement officers had not yet made their appearance. The citizens of the town took justice into their own hands. And that state of affairs makes this story possible. There was an incident – or perhaps a series of incidents – which resulted in the loss of some horses, a good deal of money, and, as Harte relates, one “prominent citizen.” A secret committee formed to decide on a response, and part of their decision was to summarily exile four undesirable members of their community: four of the six characters in our opera. Let’s meet them.

First, Cassie, a prostitute, “29” years of age (let “29” stand in for a time at which the bloom of youth is passing). Like most of her sisters, prostitution was an accidental result (about which we hear more later in the opera). Personally, she is high-strung, intense, very emotional, with a decided lack of “common sense.” Originally a farm girl from Illinois, she ran off to San Francisco with a boy who later dumped her.She is also in love with the gambler, John Oakhurst.

Lori, “38.” an older prostitute, still active, with a working name of “The Pelican,” possibly the madam. She has a good deal more life experience than Cassie, and a more jaded perspective. Her origin is unknown, but she is from German stock (“Lori” being short for “Lorelei”). She had some time in Catholic school, and has a sense of maturity to save money where she can. She has dreams of opening a shop and quitting “the life” when enough money is saved. Personally, she is foul-tempered, coarse, profane, and rough; yet she will still perform the noblest act of self-sacrifice in the opera.

John Oakhurst, gambler, about 36 years of age. Oakhurst is meticulously well groomed and fastidious about his appearance. He is also highly controlled: he does not drink or see prostitutes, shunning both love and drink. These distract from his principal, lucrative business of fleecing less-skilled men at poker. His origins are also unknown, but it seems possible that he has some education, perhaps even at a university. Highly intelligent, with basic good instincts, he is also a loner without close friends.

The fourth outcast is “Uncle Billy,” perhaps 50 years of age, a drunkard and thief: a mean-spirited, foul-tempered, antisocial, lazy and poisonous figure. Of all the outcasts, he is at once the meanest and the most pathetic. He envies and detests Oakhurst; and although a thief, a sense of misplaced moral propriety, perhaps from his lower-middle-class Protestant origins, makes him utterly contemptuous of the two whores.

These make an odd quartet, with antipathies and few normal connections (with the exception of a comradely friendship between Cassie and Lori). And yet, these unfortunates are roused, perhaps from bed, on that Saturday morning, without any time to prepare, pack, gather personal effects or provisions, marched to the edge of the town, and set on horses. The directive is given that they are banished from Poker Flat, to return on pain of death. It seems clear that none of these characters had anything to do with the events which caused this vigilante action; but the “cleansing” of the town did not need, after all, a logical or reasonable excuse, and there was no higher authority to whom the citizens were accountable.

Scene 1

Oakhurst alone seems to sense the peril of their position. The group has been set on its own, without provisions or supplies, in mountainous country, in late November. Sandy Bar, another mining camp a little less developed (and therefore more tolerant of the outcasts’ “type”) lies a long day’s ride away, and it is there that the group must head. In November, the prospect of snow is very real, and Oakhurst knows that they must make Sandy Bar by nightfall.

Alas, his companions do not share this focused urgency. Their energies are, instead, spent in emotional displays of anger, outrage, despair, and turning on each other. Oakhurst is truly the “adult” in the group, who tries his best to keep the group moving.

(Audio clip: Ensemble: March of the Grotesques)

Scene 2

Two events happen next which contribute to the group’s unhappy end. First, Cassie rolls out of her saddle and declares she can go no further. The group stops. Oakhurst decides that they could after all use a short rest, and goes off to find berries. The second event is that Uncle Billy produces a bottle of whiskey – a provision! –which the members of the party eagerly share and pass around. By the time Oakhurst returns, his companions are thoroughly sotted.

Scene 3

As Oakhurst begins to lambaste his fellows, he hears someone calling: it is a young man, Tom Simson, a prospector, and his fiancée, Piney Woods. Tom is about 20 or 21; Piney, in keeping with the customs of the time, is likely 16 or 17. Tom admires, perhaps worships, Oakhurst, as the latter returned all of Tom’s money which Oakhurst won from him in a poker game earlier that year. Tom and Piney are heading in the opposite direction, from Sandy Bar towards Poker Flat, to get married (there must be a minister there, after all). Tom and Piney are actually eloping, and have packed mules for a permanent move to Poker Flat. Tom tells Oakhurst that they will have to camp, because they are still too far from Sandy Bar to make it by nightfall. Oakhurst urges Tom to keep moving, but Tom insists that they camp together. He mentions a half-built cabin he found a short way up the road, and they agree to use that as their camp. The party, now six in number, repair to that spot.

Tom’s nickname is “The Innocent,” and he indeed possesses a strong, good instinct, which makes up for his rather average intelligence. He and Piney will sleep in separate quarters that evening, because, after all, they are not yet married. They sing a tender duet – “The Tiny Mountain Chickadee, with the shared line, “good night, my little songbird.”

Audio clip:(“The Tiny Mountain Chickadee”)

One tension which is at play through most of the story is whether or not Tom and Piney know if Cassie and Lori are whores. In truth, Piney knows it right away, but Tom is ignorant, as least for a long time, of their identity. In fact, he refers to Lori as “Mrs. Oakhurst,” which causes great hilarity among the group. But all conspire to keep Tom (and, they think) Piney in the dark about their true stories.

As the group retires for the night, Uncle Billy, in a solo aria, speaks of the rage and envy he has been nursing, and vows to return to Poker Flat and get revenge on his fellows. “They’re all a bunch o’ fools”).

The opera contains four Snow Interludes which convey the passage of time. The first, taking place overnight, begins at Billy’s exit.

Scene 4

The next morning, the group wakes to a silent world entirely covered in deep snow. They are snowed in! Oakhurst then discovers that Billy is missing: he stole their horses. In the West, stealing a horse can be a death sentence because of the distances involved (this probably explains the harsh penalties meted out to horse thieves in that time). Fortunately, Tom’s provisions were inside the cabin, and so the group can subsist. But they are now stranded by weather and the lack of horses, and these conditions obtain through the rest of the story.

Making the best of a bad situation, the ladies clean and tidy the cabin, putting up some pine boughs to make it more pleasant. Piney asks the other ladies about their plans and dreams, and then shares her own. Lori asks if Cassie is still “sweet” on Oakhurst, and she confesses her love. Lori, however, mocks Cassie for what she sees as her sentimental attachment to a man who is, in her eyes, ultimately incapable of love. All the same, Lori comforts Cassie in her genuine lovesickness, amplified by their enforced togetherness.

Scene 5

It is now two nights later, and the snow has continued to fall without sign of stopping. The group has managed to build and sustain a fire, and sing, dance, and tell stories to pass the time. Tom asks for peoples’ own stories, which they are naturally reluctant to give. Cassie, however, is willing to tell hers, and she tells it by way of a ready-made song which she would sing on the stage of the dance-hall in Poker Flat. Her “Saloon Song” is a set-piece song delivered to the audience in the hall, with Cassie’s fellow cast members joining her not as spectators to that song, but as fellow performers.

Audio clip: https://andrewesimpson.com/works/Pokerflat.html)

The theoretical twist is that the entire cast turns toward the audience for this single number, and by singing to them, acknowledge their presence. The rest of the opera (with the exception of one aside by Oakhurst in Scene 8) is done as a self-contained story.

Tom then shares a reading of Homer’s Iliad (he can read, therefore); the libretto takes an opportunity which Harte does not to draw a parallel between the outcasts and the Trojans, who are similarly prisoners besieged by hostile forces (Greeks or snow).

As the group retires, Lori remains behind. She realizes that the snow will likely not stop, and she knows, somehow, that she will never reach Sandy Bar or realize her dream of opening a milliner’s shop. Her extremity causes her to lament her wasted life; desperate for some redemption, she hits upon a desperate plan.

Snow Interlude 2 is driving, powerful, like the ever-intensifying snow which continues to blanket the stranded party.

Scene 6

Two days later. Lori has declined rapidly and is visibly weak; the three ladies sing of their desire to fly away from this place and be anywhere else, quoting a Psalm: “If I had the wings of a dove, I would fly away from here…”

Audio clip: “Trio: Wings of a Dove”

Two days later, Lori is on the point of death; she reveals to Oakhurst and Cassie that she has been starving herself so that Piney can survive on the food she has not been eating. She tells Oakhurst that Cassie loves him: “Open your eyes, you damn fool.” She dies, and the group buries her in an improvised grave outside.

Audio clip: “Lori’s Sacrifice”

Scene 7

The next morning, Oakhurst and Tom agree to a last-ditch plan: Tom will attempt to return to Poker Flat on improvised snowshoes and bring back a rescue party. He says goodbye to Piney, and they reprise their earlier duet (Mountain Chickadee). Their earlier “good night” has changed to “goodbye,” as the pair recognize that they will not see each other again.

Oakhurst starts to go with Tom for part of his journey; before leaving, he comes back and unexpectedly kisses Cassie, to her astonishment. He loves her, after all! Then he is gone.

Scene 8

Oakhurst, having parted ways with Tom, is now alone. As a gambler who sees everything as a calculation, he reckons that the group’s luck has entirely run out, and that there is no advantage in continuing. Aria: “Life’s a Game of Poker.” He has decided to kill himself, which is the logical outcome of such a thought process. However, his emotional side finally asserts itself. The control on which he prides himself has gradually broken down, and by taking a few swigs from a whiskey bottle, he indulges in his two prohibitions – love and drink – in the same hour. Without the prospect of future gambling or need to hold onto his winnings, he lets all go to chance. After asking Cassie’s forgiveness (“don’t hold it against me”), he shoots himself.

The final snow interlude is a complete white-out: an intense and totally intense screen of sound. This gives way to a tender, slow lullaby on bell-like tones.

Scene 9

That evening, Piney and Cassie – the two remaining characters – are huddled together in the cabin. The fire is dying, and their strength is also near its end. Cassie wonders why Oakhurst has not returned; like Lori, she regrets those actions of hers which led her to this point. She begins to confess her identity to Piney, who interrupts to say that she already knows. And, separated as they are from any society, there is no one left to judge her, either. And in this there is liberation. Cassie, now nearing death, asks Piney to sing to her: Piney sings a simple lullaby which her mother taught her. Cassie passes away quietly.

The final moments of the opera are a transformation. As the morning arrives, a beam of light enters the cabin. Small at first, it grows stronger and brighter. Piney tries to awaken Cassie to see it: she sees the Angel of Death, who is kind, smiling, and looks like Tom. She reaches out towards the light and the vision: a moment after she collapses, Tom steps into the cabin leading a search party, a moment too late.

Why tell this Story?

I first read The Outcasts of Poker Flat in high school, and the story has stuck with me. And, while rolling my eyes at the dreaded teacher–ly question, “What is the author’s THEME in this story?” it does seem worth talking about some of the embedded messages.

Probably the most important theme for me is Harte’s display of the artificiality of a society and its collective values. The story throws together six characters, four “bad” and two “good;” but removing them from a social context also makes those valuations meaningless. In the wilderness, alone in a cabin, who is to say that Piney is “good” and Cassie “bad”? In extremity, there is the realization that all are equal before death, all equally fragile before the immense power of nature.

This also speaks to the nature of American society, famously moral and puritanical even while so often courageous, generous, and daring. The Gold Rush, the context for this story, pries up the underside of greed, a persistent strain in human behavior, but one particularly ascribed to Americans and their supposed knack for business acumen and acquisition. The contradictions of a strongly religious civilization built on hard work and wealth which yet maintains a harsh, demanding code of private conduct are as evident in Harte’s time as in our own. (I thought about setting this story as a contemporary one, stranding entirely citified characters in the wild without food and water or cellphone service, and this story could effectively be told.) The theme of humanity’s fragility on earth is, after all, relevant to every time and place.

There is another moral component, which is that the extremity of the outcasts’ situation forces them to “show their hands” and act in a manner which reveals their characters. Piney, Cassie, and Lori grow in the story – Lori and Piney most of all; Oakhurst shrinks from being the man in control to the one who abandons all control and chooses selfish self-destruction; and Uncle Billy and Tom remain essentially the same, although one benefits and one harms the group. Each character reveals his or her basic nature: some are generous, some are villainous.

Nature is another of Harte’s themes. From an immediate commercial perspective, Harte, writing mostly for East Coast readers, satisfied a desire for tales of adventure stories from the vast, exotic region of the “wild” West. Jack London told similar tales of the power and danger of nature. While we spend much time – rightly – lamenting our disastrous impact on the environment – it is useful also to remember how potent is nature, and how dependent we are upon innumerable tiny links in a vast network. Stranding a party of six socially insignificant characters in a Sierra blizzard allows us to put ourselves in their place, and imagine what we might do in their boots.

LINKS:

The Opera website: https://andrewesimpson.com/works/Pokerflat.html

Andrew Earle Simpson’s composer website: https://andrewesimpson.com