When Washington National Opera presents one of opera’s top examples of musical comedy next spring, it’s only fitting that the production will star a singer whose background sounds as ready-made for Broadway as for the opera house. Isabel Leonard, who will sing the lead role of Rosina in Gioachino Rossini’s laugh-filled romp The Barber of Seville, attended the Joffrey Ballet School, went to the high school made famous in the movie Fame, and once stepped into a key role in Leonard Bernstein’s On the Town when the show’s Broadway cast came to the San Francisco Symphony to do semi-staged performances minus one of their actresses.

At the Metropolitan Opera, Isabel is known for the high bar she’s set for stage business and physical comedy in what can otherwise be the rather earthbound business of opera. The twist is that as an operatic mezzo-soprano, she follows the centuries-old convention of opera mezzos playing both women and men according to the desires of the composers. She once even played both a young boy and a grown woman in the same evening in the case of two contrasting one-act operas by Maurice Ravel. But a passion for exploring in greater depth the music of Bernstein in the centennial year of his birth also has her developing a full recital program of the surprising variety of Bernstein’s music, which she will bring to the Kennedy Center Terrace Theater prior to the opening of The Barber of Seville.

Recently I talked with Isabel by telephone in between her engagements around the country and internationally. Here are excerpts of our conversation:

David Rohde: Tell me how you got into ballet as a kid and what it brings to you now on the opera stage.

Isabel Leonard: I think just to have that physical discipline of dance from a very early age has always given me the ability to move. I know that might sound very simple or trite, but just the ability to move from point A to point B in such a way that we can feel your character’s frustration or whatever it might be, you’ve developed a vocabulary of expression that is coming from your body and not just from your voice. And not even meaning your singing voice, but your voice just as words.

How many years of training did you have at Joffrey?

I started when I was about five, and I was there, I think, until about 11 or 12. Right around the time when I had to make the decision as to whether I really wanted to do this or not.

Would you say that your ability to move on stage helps the other people on stage that you are singing an opera with?

I think so. I think that anything that you do on stage, if it is honest and true to the character that you are portraying, and if you are being open and generous to your colleagues, then nothing but good can come from that – for everyone. I think that there’s always a positive ricochet effect.

Is that a different challenge in opera as opposed to musical theater? I’m generalizing of course, but very often, for 10 or 15 minutes, you’re stuck on the same emotional point, and you need to be doing something other than simply the lyrics in the music to bring it across. Or am I saying something that is offensive or not valid?

No not at all! Certainly, that happens in something like a Handel opera, for example. Or a lot of composers who tend to repeat the same words [laughs]. It’s definitely helpful to have other ways of expressing things throughout those repetitive moments, because you can, as the actor, continue the storyline forward, even if it’s just for you, with other modes of communication.

Tell me how you decided as a kid to sing seriously, and what the role was of the children’s chorus at the Manhattan School of Music in that.

In grade school, I had started singing in the choir in fifth grade. My mother had been exploring other ideas for choirs and things, just out of sheer curiosity, and she found out that the Manhattan School of Music was starting a new children’s choir. She asked me if I wanted to audition for it and I probably said no at first, and then she probably said, “Well you might not get in,” so I said, “Fine, I’ll audition!”

Smart woman, your mom.

So I did and I got accepted to this choir, and Christine Jordanoff was our choirmaster. She used to commute in every Saturday from Duquesne University to teach us. And I would say that that was really the beginning of my formal music education. Christine Jordanoff was the one who sparked, I mean there was already a love of music and singing, but she was the one that sparked the joy of music and singing. And I did a lot of harmony because they knew I could! So I was always put sort of in the middle. I would say that all of the harmony that I’ve had to sing in my life has served me well. It’s its own ear training.

I remember walking home from my choir practices with one of my friends and she and I would sing the whole way home from MSM. We would sing in harmony, we were 12 or 13 and we would just sing and sing and sing. We learned a lot from Miss Jordanoff and her assistant Pamela Simpson who were really instrumental in helping me move ahead.

Pamela Simpson was the one who helped my mother when I was figuring out what to do for high school, and I wanted to audition for LaGuardia [the LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts]. And when I went on from LaGuardia, they put me in touch with this gentleman who ended up doing a little coaching with me and playing the piano for my pre-screening tape for Juilliard. And he was the one that said, you should look into studying with [legendary opera teacher] Edith Bers if you can, she teaches at Juilliard, I will put you in touch with her. I mean it was just one thing to the next. It was like someone handed Christine Jordanoff a baton that went from one person to the next person to the next person and I just kind of jogged steadily alongside all of them.

You had almost a razor’s edge decision as to whether to go into musical theater or opera. I hear it depended on a single day visiting colleges, is that right?

It really did. I actually didn’t know whether I wanted to go to CAP21, which is part of the musical theater program down at NYU, or whether I wanted to go to Juilliard. I really didn’t have a perspective of either place. But I had been doing musical theater in high school, and singing with the jazz band, but also with the classical choir and doing solos and things like that. At that point, you know, the singing itself was all the same. And I just didn’t know, I really wasn’t sure what to do. So I decided that if it was possible to spend half a day at both places, I would. So I went down one day to NYU, and then I spent half a day one day at Juilliard. And I just felt better the day I was at Juilliard. The students that I met, the environment I was in, for whatever reason it felt better that day, and that was it.

Was it a conscious decision to go for the mezzo repertory in opera, or did somebody decide that for you?

No, when I auditioned at Juilliard, I don’t know whether I had heard or whether I felt that there were probably fewer mezzos at the time. So I just checked the mezzo box for no other reason than I knew that I could probably sing both. Or maybe by the time I was a [high school] senior it was a click more comfortable. But also, what did I know at that point? I had no real concept of what the gamut of the soprano repertoire was at that point, nor what the gamut of the mezzo repertoire was. I used to wake up in the morning listening to [soprano] Renata Tebaldi singing Vissi d’arte [“I lived for art, I lived for love” from the Puccini opera Tosca] and I could sing along. As long as you’re singing in a healthy fashion, and more so age-wise and character-wise, I don’t really have problems playing around with different titles of rep, right?

Well, you’re an operatic mezzo but you clearly sing high B’s and C’s.

Right.

So how do you define that? Is there a better language for it that people can understand about opera categories?

Yeah, I mean I would say that if you’re trying to create a sort of a generic distinction between a typical soprano and a typical mezzo, it’s not so much about the range as it is where the voice is most comfortable. So I would say that a typical soprano is a little more comfortable singing in a higher place in the voice. Whereas a typical mezzo would choose a little bit of a lower place, not necessarily by a lot, but just a slightly lower place. And it can be as simple as that. Then, of course, other factors contribute, which could be potentially more noticeable. A mezzo could have a darker, richer sound.

Well, you certainly do!

But I’ve heard some sopranos who have a darker sound than the mezzo who is singing in that same production. The line is very fluid.

As a mezzo, though, you play both women and men on stage, or girls and boys. Tell us what the history of that is in opera, and the kinds of men’s roles, or “pants roles,” that you’ve played.

Well, there are lots of composers who wrote young men’s roles who were sung by women and it was sheerly to have a vocal quality that would depict a young man’s voice. I mean, young men’s voices change at different times in their youth. And if you are trying to depict a 12- or 13-year-old, there’s a chance that his voice hasn’t dropped. And of course, the classic example would be [the comic character of] Cherubino in The Marriage of Figaro where, depending on the director he could be within a range of age, but he’s still on the young side, he’s not a full-grown man. It’s kind of a fabulous way of portraying a young man, rather than having a man try to sing the role and “act youthful,” just to have a woman singing it, there’s sort of that naturally androgenous characterization that comes from a woman singing a male part.

I mean, think of the young boys that you know that haven’t quite decided that they want to be all grown up or all macho, or whatever example that they may have in front of them, whether it be good or bad. They’re the sweetest things, and I say that of course because I have a 7-year-old son. They’re just so sweet they’re doe-eyed, and then they’re completely confused about what’s going on with them, and they’re all over the place, they have the attention span of a gnat, and it’s wonderful!

How many times have you played Cherubino in New York, and how many times have you played it elsewhere?

I really don’t know the number. I mean I’ve done it at least three times at the Met. It’s been quite a lot. I mean, my first was in Santa Fe, I’ve done it in Vienna, I did it in Cincinnati, I’ve done it in Paris. There was a season that I did Cherubino in between every other role that I did that season!

Well, when you go from Cherubino in The Marriage of Figaro to a Rosina in The Barber of Seville, I mean are they like the two greatest musical comedies ever written?

I do think they’re really quite fabulous! They can be really bubbly, which is great. But it all depends on the director.

Tell me about your different productions of The Barber of Seville, because that’s what we’re going to be seeing you in next here in Washington. How can that differ among directors?

Comedy is like salt, you sprinkle it on for taste. A lot of directors like to really sort of lay on thick the slapstick. Others like to be more subtle about it. Some like to play the piece straight, which I actually don’t mind at all. I think sometimes some of the more funny things come from the rather tragic scenario that’s in front of you. It’s sort of that fine line and the balance of the two.

On top of that, not only do you have different types of comedy within, let’s say, productions in the United States when you go overseas, you know the concept of comedy is different in every country. We know because we talk about British humor as Americans, right? So the Brits have a sense of humor, the sort of dry wit that we speak about when it comes to British humor. If you do a production of The Marriage of Figaro in England, we know that the comedy comes more from that side.

And I can tell you that having worked in France quite a bit, they have their own version of slapstick but it’s not the slapstick that we would do here in the United States. If I were to do something at the Met, for example, and if I were to do the exact same thing in France or another country, it may or may not work out. All of these are very subtle things. Sometimes it’s just a different type of physical gesture – not necessarily bigger or smaller, but different. There are things that when I’m there, I can’t quite put my finger on them but I sort of glean from the culture if that makes sense.

It sure does. Tell me about the character of Rosina. In musical theater, people see a stowaway and they think of some very one-dimensional characters like Joanna in Sweeney Todd. But Rosina is different, she’s very crafty.

She is very crafty but she’s not in a great place in her life. She has been cooped up in a house and taken care of by her guardian. We don’t really know a lot of the backstory, at least when you come into the opera with fresh eyes, you don’t really know what’s happening. What you see is a young woman who’s being in some ways held back against her will. Then you find out that [her guardian] Bartolo wants to marry her, which because of the way that the opera is being laid out in front of you, immediately allows the audience to feel some disgust with this idea. And then as you see the story unfold, had she met or not met “Lindoro” – you know, Count Almaviva [a wealthy young man who pretends to be a poor troubadour named Lindoro] – she would have found some way to get out. She was searching desperately for how to get out, and it just so happened that she fell in love in the process.

Do you love that moment when Rosina is singing when she changes from being sweet and gentle to very assertive?

In the aria she suddenly says, “If you cross me I’ll be like a viper,” and it’s just kind of delightful. It’s like somebody going along saying, “Truly I’m really a nice person, I’m really easygoing, everything is just fine,” but she’s probably been on edge for some time with everything going on in the house. She wants new scenery and it’s almost as if it escapes her, I think, without her really planning on it. It’s like your good friend saying, “You know, I just don’t understand, everything was fine today at work, but then you know what happened? I just wanted to throw the stapler across the room!” [The moment Isabel is describing is in this 2-minute clip from the Metropolitan Opera’s abridged all-English-language version of The Barber of Seville.] I feel like it’s sort of just part of her personality, she does not apologize for her nature. Not to say that there’s anything to apologize for, right? I feel like she’s quite fearless. And that’s a lovely characteristic.

A couple of years ago for Washington National Opera you played the title role in La Cenerentola – well, the opera here uses the English titles of the Rossini operas, so Cinderella. How do the two roles compare? What do you take from that experience when you were here in Washington in 2015, to the next one?

Well, I did it in Washington but then when I actually did it at Chicago Lyric Opera it was the same production. And I did [a different] production in Munich a bunch of years ago, which was lovely. Cenerentola, or Angelina [the Rossini opera gives the specific name of “Angelina” to the Cinderella character], she’s different. She has a different kind of fire than Rosina. Actually, I wouldn’t call it a fire in her. I’d call hers more like warm, glowing embers. Rosina is a very kind person, but Angelina is by nature incredibly warm, and she doesn’t choose to be warm, she just is that way. But that also makes her so difficult to portray, because a lot of times, when you’re trying to portray somebody who is truly at their very core simply a good person, it can come across perhaps as weak, or a bit of a pushover, or that they don’t have much of a backbone or any of those things. I find that actually kind of a fun challenge to portray her, so that the audience doesn’t feel like she’s a victim so much as a bad lot in life at this point.

Totally different kind of opera – with legendary conductor Seiji Ozawa you’ve recorded one of the Ravel one-act operas called L’enfant et les sortileges [“The Child and the Spells”] in which you literally play a petulant little boy. But you also perform Ravel’s other one-act, L’heure espagnole [“The Spanish Hour” or “In Spanish Time”] in which you play a grown woman.

So very fun. And I have to say that the evening that summer when I did both L’heure espagnole and L’enfant et les sortileges in the same evening was just fabulous.

Where exactly was it that you sang both operas together?

This was in Japan, with Seiji Ozawa. He only conducted L’enfant et les sortileges. But it was lovely to do L’enfant et les sortileges, and then at intermission change over completely into Concepción in L’heure espagnole. So I went from a young boy to this very sort of pin-up-ish woman, and it was great, it was just so much fun. I can’t remember how many performances exactly, but we were there for about five weeks total.

Do you find Ravel’s music very complicated to sing?

It is complicated. Neither one of those two scores is easy!

How did you learn it?

I learned it like I learn anything else, you know, you plunk out notes and you listen. But I did have one of my most favorite French coaches, Pierre Vallet, help me learn both of them. We drilled and drilled, and he has always worked very closely with Seiji and he was also in Japan. We worked a lot of course in New York before we traveled out there, and then we continued to work on both of them while we were in Japan. He is the reason why not only I love these pieces so much but also why they were so successful because he’s brilliant.

Tell me about one of your CDs called Preludios. Several American opera singers have recently recorded Spanish disks, but you found some wonderful, off the beaten track, material on there. How did you put it together?

Do you still do some of this material in your recitals, or are you really focused on Bernstein at this point?

Right now I’m definitely focused on the Bernstein. It is very new. I mean, you’re familiar with Bernstein to a certain degree. But once again I put together a recital of 22 or 23 songs that are all new. It’s a massive load of things to learn and memorize!

Are you doing this recital because 2018 is Bernstein’s 100th anniversary?

It’s his anniversary, and I had been given the inspiration by Matthew Epstein who was my first manager, and he said you should really do this, and I thought that’s really a great idea, so I did!

Last year you did a run of On the Town with Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony. Tell us the role you played and how you felt about that show. I mean, all of the Bernstein musicals, not just West Side Story, are popular here in Washington.

Oh, it was so fun. I played Clair de Loone. And it was with the Broadway cast who all came out [to San Francisco]. I can’t remember why the woman who was the original Clair de Loone couldn’t be there, but I got to do it with them, which was fabulous. I was put into a situation where they all know each other and have done the show with each other for years. They were the nicest people to meet – Tony Yazbeck and Alysha Umphress and Jay Armstrong and Megan Fairchild and Clyde Alves – just great. It was just all shades of fun.

Are we ever going to see you in a staged musical, or is that not on your radar?

I would love to, it’s just a matter of finding the right kind of thing. You know they book very differently than we do [with fixed runs of opera]. In order to do something like the typical Broadway show, which would be 8 shows a week, it would be pretty difficult. It’s hard to line them up. But I would love to do a short run of something, it would be fabulous. Like this West Side Story [which she performed recently for one week with the Philadelphia Orchestra] was just so great. If we could just do a staged production – before I get too old [laughs] I would love to sing Maria in a fully staged production of West Side Story. That would be a dream.

In your fantastic kids’ video with the characters of Murray Monster and Ovejita from Sesame Street, you liken learning to sing opera to learning a sport. You and some other current opera singers are known to be very conscious of physical fitness. How do you fit that into your life, you’re traveling all around the world, and you’re a parent?

I would say that I generally try to stay healthy. I don’t avoid all the treats that I like – if anybody follows me on Instagram they’ll know that! But I try not to indulge in anything to excess. Just being aware, that’s all it is. I mean I haven’t been in a gym in a month, I’m going to a gym for a spin class today and I’m terrified. But just because of my dance background, physically my body likes to be in a certain place. At this point, I try not to be picky about it, because the key is, if you get locked into any sort of routine, I feel like with the way our lives are, and with all the travel, it’s very difficult to stick to any sort of really strict routine. And even more difficult, I think, when you have a kid. So you just throw it in there wherever you can, is how I feel about it.

You know, there are plenty of times where I’ll say, “Oh Isabel, you really need to pull it together, girl!” I’m actually in that mode right now because of Cherubino, because he’s “coming back” in December [at the Metropolitan Opera in its production of The Marriage of Figaro]. I know exactly what I need to do for him, because I was the first one that did Richard Ayres’ production. So I feel like I set a standard that I’ve been jokingly yelled at for, at the Met. You know for all the other people who come in to do the production. They’re like, “Why did you do that? We don’t want to do pushups. Thanks a lot, Isabel!”

Well, let’s back up. Tell us for the record what it is you do physically in that role.

Well in that particular one, I created this Cherubino – well Richard Ayres, of course, “created” this Cherubino – that runs around, is incredibly active, jumping all over the place, he climbs up on the armoire, he jumps out the window. It’s a 10-foot drop and the dancers catch me. And I do real, legit pushups on the stage. All these things where I’m looking at myself now saying, “Okay, girl, you’ve got about a month and a half, you better start getting back to work to uphold your own standard!”

Tell me about the all-Bernstein recital you’re doing in various cities and next April at the Kennedy Center. What do people hear when they go to one of your recitals that they wouldn’t have known about Leonard Bernstein?

I enjoy all the music and everybody has their different opinions about the program itself. So much of his music is really beautiful, many people will call them lollipops. It’s tricky when you’re putting together a program. You know that you want to get some variety in there. But you want to put music in there that you like and that the text means something for you. Not only are you vulnerable because it’s you singing all the time, so now you’re vulnerable for the critique of what you’re singing. And the question of “Why did she program this?” and “Is she trying to tell a particular story?” or whatever it is, right. And sometimes you say, “It’s because I like the music, and I like the text.” And that, right now, is what’s most interesting.

I think there’s definitely going to be some pieces that people have just never heard. If your only experience with Bernstein is things like West Side Story, you’re going to assume that that‘s the kind of music that he wrote all the time, and it’s not. He wrote some rather modern, almost atonal music. I mean, one of the songs is called “My Twelve-Tone Melody,” and it is very much that – with a little twist at the end that is the reason that I sing it in the first place. He wanted to be known for more than just his musical theater pieces. And for me, so much of this music has to do with the text and all of the messages that he clearly was trying to get across in his music.

Thank you, Isabel!

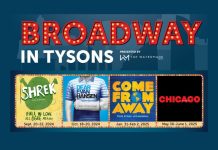

Mezzo-Soprano Isabel Leonard will perform a solo concert as part of both the Fortas Chamber Music Concerts and the Renée Fleming VOICES series on April 15, 2018, in the Kennedy Center Terrace Theater. She will then star in in Washington National Opera’s production of The Barber of Seville at the Kennedy Center Opera House from April 28 to May 19, 2018. For Isabel Leonard’s complete international schedule, see her performance schedule.