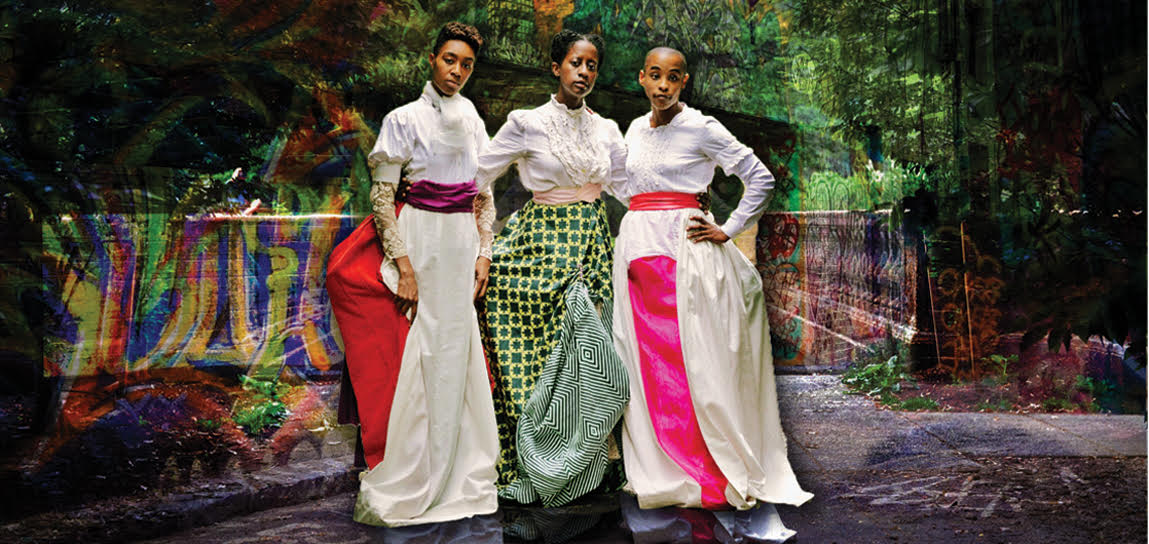

District-based solo performer Holly Bass creates in so many media and art forms I can’t keep up with her—and I’ve been covering her for nearly a decade. Her latest devised work, a dance-theater piece, begins a weekend run July 26, presented by Theater Alliance in collaboration with the Anacostia Playhouse. The Trans-Atlantic Time Traveling Company is about a sisterhood of three women who time-travel from the present to the 1860s when they become freedwomen, in quest of what it means to be free. Bass’s long commitment to social justice emanates with a passion for challenging staid ideas—artistic and otherwise—onstage. An engaging speaker, Bass took some time from her creative pursuits to answer a few questions on her process and her inspirations.

Lisa: As a multidisciplinary artist crossing genres from dance, theater, performance art, video, photography, poetry, and installations, can you share how you determine what works? Does the concept come and then you determine what art form you’ll use?

Holly: I get most of my ideas for new work as I’m thinking about current events or social justice issues. From there, my imagination usually lands on something really absurdist. For instance, I came up with the “bootyball” or “body orb” costume piece [see video below] as I was thinking about Sarah Baartman—the South African woman who was smuggled to Europe in the 1800s and was basically displayed as an exotic curiosity because of her large backside—and comparing that to the objectification of black women’s bodies in hip hop music. It was the mid-2000s and big booties and bounce beats were everywhere. I thought what if you had a booty so big it was like a giant rubber ball and you could bounce on it and almost defy gravity. And from there I started to imagine these futuristic women who could travel long distances and support themselves with the energy stored in their very large derrieres, kind of like how camels store nutrients in their humps. I also thought about the theory that Baartman’s buttocks inspired the fashion of the bustle. So you basically have all of these white European women idealizing and imitating a particular body feature on the one hand, but denigrating the women who actually possess those features. And I’m using the word “denigrate” quite intentionally here!

Fast-forward a few years to 2010. The Smithsonian African art museum asked me to create a performance inspired by Yinka Shonibare’s work—he creates these headless mannequins dressed in Victorian attire. That 20-minute performance was the first iteration of what is now an evening-length work, The Trans-Atlantic Time Traveling Company. Only now, I’ve been thinking a lot about ideas of freedom and the phenomenon of doing something “while black,” as well as some of the current administration’s policies that have this really ugly current of declaring certain folks illegal, undesirable, not-quite-human. I mean, who is to say that one group of human beings should be enslaved and another group free? How does this continue to happen for centuries?

As an arts journalist, you coined the term “hip hop theater.” Can you explain what that means and how it differs from traditional theater? And how has “hip hop theater” evolved since you first used the term?

I can’t say that I “coined” the word per se—it really came from within this loose collective of artists—but I was the first journalist to use it in print in 1999. A lot of us grew up on a certain brand of socially-conscious hip hop, so these rhythms were showing up in the plays and dances and music people were creating. It was very multidisciplinary. I’m not sure we knew the term “postmodern” at the time, but we were definitely all about combining things that weren’t meant to go together and giving forms new meaning. At that time folks like Danny Hoch, Kamilah Forbes, and Chad Boseman were writing, producing, directing, and performing this kind of work, people thought we were a little crazy and that it wouldn’t last. And now Hamilton—a musical that is entirely in rap form—is one of the highest-grossing musicals in American history.

Vaudeville, burlesque, or variety show forms seem prevalent in your work. As a youngster and young adult, what did you watch that introduced you to these forms?

(Laughs) I have no idea! I certainly wasn’t seeing any burlesque growing up in my family, which was very sort of proper, respectable, religious black folks. But you know actually the black church is what really informed my work to tell the truth. That was where I did my first oratory recitations and plays. Our church also had dancers. This was in the California Bay Area where I grew up. I remember one of the women who would choreograph the children’s plays was a former Ailey dancer. So there was a rich cultural tradition in the church, not just cultural as in identity but very much so in terms of the arts. We were the folks who would leave service all dressed up and head to whatever Broadway production was on tour afterwards. My parents definitely encouraged me in writing poetry and studying theater and dance, so I was very fortunate in that regard. I also recently heard a talk by Arthur Jafa [an African-American filmmaker/videographer] about how long traditional black church services are and how that kind of trains you to understand durational work. I had never made that connection before, but it totally makes sense to me. Like, of course I’m going to make a seven-hour dance performance with no food or bathroom breaks because as a small child I sat through four-hour services in my grandmother’s church in Georgia.

For your latest work, The Trans-Atlantic Time Traveling Company, you are delving into Afro-futurism. For those unfamiliar with the genre, can you explain what Afro-futurism means and share with us how you discovered this genre?

I first discovered Afro-futurism through the work of novelist Octavia Butler. There are many definitions, but in a nutshell I think it boils down to presenting the case that black people will in fact exist in the future. A lot of films and futuristic narratives like to erase blackness—as do films and books set in the past. It’s important that we continue to push complex, fully developed representations of black people in the present, past, and especially the future. The editor of the anthology Octavia’s Brood, adrienne maree brown, said all activism is science fiction because in order to change the world we have to envision a world that we’ve never seen. I love that.

Much of your work mines elements of popular culture and history. What historical influences, texts, or time periods inspired you to write The Trans-Atlantic Time Traveling Company?

So many! The text is full of quotes from songs and movie references, everything from David Byrne to Kate Bush to Donny Hathaway. And I’m referencing films like Purple Rain and The Wiz quite a lot. I also looked at what songs were popular in the 1850s and 1860s. To make a Shirley Bassey reference, it’s all just a little bit of history repeating.

You are not afraid to wrestle with social justice issues in your work—on stage, in photography, and in installations. Can art change society or individuals?

I think art can absolutely change individuals and individuals can change society. I mean art isn’t going to end genocide or famine, but I believe the best of art challenges our set thinking patterns, opens our hearts to be more receptive, and reminds us of our shared humanity. If you are connected deeply to a sense of humanity—your own and others—you feel obligated to protect and defend that, to speak up when injustice is happening. Maybe not to risk your actual life, but at least to risk your social standing enough to speak up in defense of others whose safety and rights are being threatened. We’ve been lacking in that as a culture, but hopefully that can change.

Many performers of color—choreographer Kyle Abraham said this to me most recently—have stated that a black body on stage is in itself a political statement. What are your thoughts on that? Has that historically been the case or is this a recent development?

Absolutely agree. All my life I’ve been in situations where I think, I was never intended to be here. The men who created Ivy League schools never intended someone like me to be there. The men who created the National Gallery and the Corcoran Gallery of Art did not do so with me in mind. And yet, here I am disrupting the space and helping to bring in “the community” through my work as a performance artist and educator. So it’s not new. And I definitely see myself as part of a lineage of folks who continue to smooth the path, or sometimes create the path, so that others can enter more easily.

Do you aim to make your art political? Is all art political in these charged times?

I’m certainly from the school of thought that says not making a political statement is a political statement in and of itself. But I don’t think I aim for the political. I’m really just creating the things that I would like to see that I don’t necessarily see enough of in the world. I don’t see enough of black sisterhood in popular representation. I don’t see enough black love represented or black joy. I see it in real life, every day, but I don’t see that life reflected enough on screens and stages, so I feel compelled to do something about that.

You have stated that you often included “a tangible exchange with the viewer.” Tell us what you mean and why that is an important aspect of your performance.

It’s really the idea of having skin in the game. For example in my performance, Pay Purview, I ask the audience to contribute money in order to see the rest of this absurd peepshow, and it really changes the dynamic between me as the performer and the audience. There’s a heightened awareness of their complicity in consuming and enjoying watching a black female body onstage. It’s like, “Put your money where your mouth is.” And sometimes it’s not always about money. In The Trans-Atlantic Time Traveling Company, we’re going to be offering people medicine and healing in different forms, like a tablet or being anointed with oil, so it brings up all of these ideas of trust and physical intimacy that don’t typically happen in traditional theater. I’m excited about that.

[Related: Read John Stoltenberg’s workshop performance report on The Trans-Atlantic Time Traveling Company]

The Trans-Atlantic Time Traveling Company plays July 26 to 29, 2018, at Theater Alliance in collaboration with Anacostia Playhouse performing at the Anacostia Playhouse – 2020 Shannon Place, SE, in Washington DC. For tickets, call the box office at (202) 241-2539, or purchase them online.