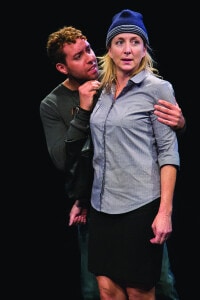

When Michael Kevin Darnall plays a character who is the focus of a long scene and we can watch every nuance and shading of his emotional expression without interruption, he can be transfixing. When I saw him do that in Mosaic Theater Company’s production of Gilad Evron’s Ulysses on Bottles, I wrote:

The actor is delivering a depiction of Ulysses’ inner turbulence that is so daring and disclosing it drives the momentum of the entire production.

I saw Darnall do that again in Bosco Brasil’s New Guidelines for Peaceful Times, now playing at Spooky Action Theater.

The character who drives the plot is the Brazillian immigration interrogator Segismundo, played terrifically by Carlos Saldaña. He’s calling the shots. He’s the proactive one. But it’s Darnall’s more reactive performance as the Polish émigré Clausewitz that really drives the emotional momentum of the play. It hooked me and gripped me even beyond the storytelling in the play itself. So I wanted to talk with him to ask him how he does that.

I had no idea what a wonderful story I would hear.

Michael: I consider myself to be a very sensitive person. I’ve always been, ever since I was little. I’d be watching a sitcom and something sad would happen on The Golden Girls or 227, and my mom or grandmother would look at me across the room and say, “Kevin, it’s just a show.”

I get really wrapped up in stories that tug on my heartstrings, and there’s something about Clausewitz that is so gentle and open and hurt. And that really touches me. We talked a lot about his sense of wonder. That’s a word the director Roberta Alves used a lot in rehearsal. His childlike wonder. His naivete. His chosen profession and how he approaches life with a sense of exploration and joy in the doing.

He was an actor in Poland and after his life there crumbled he decides that he wants to change professions and do something more worthwhile, more “real.” He decides to become a farmer in Brazil. It looks like an arbitrary decision but once he unravels what he’s been through and what led him to that decision, you see why he would give up art and deem it as less important than manual labor.

The sensitivity you have felt since you were a child seems key to what I see in your performance, because it is so unusually unabashed and rare. Especially in anyone who is raised to be a boy. How did you grow up and keep it?

Well, God knows, there were plenty of attempts to drive it out of me, whether my peers or family members who saw that I was a little too soft, a little too weak. I would cry at card tricks, you know? But if anyone asked me what my secret is, what makes me a good actor if you think I am one, I would say I have it all to thank to women, the women in my life. The incredibly kind, sensitive, giving women who raised me. My mother. My aunts. My grandmothers. Of course, there were wonderful men in my life as well. My dad. My grandfathers. But there’s something about what I saw that women do, and it’s that generosity of spirit.

I’m so taken by people who aren’t afraid to be their authentic selves. To cry when it’s time to cry. To shout when it’s time to shout. To completely fall apart when it’s time to completely fall apart. They have such faith and strength. They know they’ll bring it all back together. And I’ve always carried that with me.

I grew up in the Baptist/Pentecostal church, so I spent a lot of Sundays in church with these women. I don’t know if you’ve ever been to a black Baptist church or a Pentecostal church, but when the spirit moves it’s an amazing thing to witness. Seeing your mother crying and laid prostrate on the floor—and 30 minutes later we’re joking and going to have fried chicken at my grandmother’s house. I was so taken by the way these women would let spirit move through them.

And also actresses. I will never forget. It was summer break and I was at home by myself flipping channels. I landed on HBO and it was the end of A Trip to Bountiful with Geraldine Page. And I was watching this woman behave in such a way—her hands and how she would touch her face. And I had the nerve to think that this woman was stealing from me, that Geraldine Page was doing my shtick! I was just so taken by her.

And then I went to acting school, and Joan Potter—my great acting teacher at SUNY Purchase, Conservatory of Theatre Arts—she had actually been the understudy for Geraldine Page and Kim Stanley when they did that famous production of The Three Sisters at the Actors Studio that went to London. Joan would tell these great stories about her friend Gerry Page and Kim Stanley. And funny stories about Sandy Dennis. So then on break I started to research these women.

Seeing their performances on video, I knew I was watching very much more accomplished, much more gifted, clearly older people than I, people who had lived a lot more life at that point. But I saw something in the way that Geraldine Page, Kim Stanley, and Sandy Dennis approach a line and a moment—something that I saw in myself. Those women changed my life. And I aspired to be as good as them.

Hearing how women inspired your acting technique, I’m recalling other roles I’ve seen you play, like the boyfriend in Yentl. And the guy in Animal who’s like—

Oh my gosh.

He’s a pretty over-sexed man, right?

Oh yeah.

Were you using this same woman-inspired acting sensitivity on him?

Well, you know in 2018, we’re trying to be more mindful about using words like feminine and masculine and what it means to be a woman or a man. It’s not that I am ever-shifting “feminine” qualities into “masculine” qualities. What I’m attributing to femininity is that willingness to be open and available and sensitive. And as a guy who went to acting school with a lot of testosterone in the room, I see how men get tight and guarded and stiff when acting.

Inspired by some wonderful women, I’ve always been determined to have the same amount of trust, freedom, courage, to be vulnerable. I think that may be what you’re seeing. I don’t feel the need to be macho on stage.

I’m flashing back to your role as the captured Union captain in Father Comes Home from the Wars. That vulnerability was coming through even in that character. It’s not that you’re playing the same character all the time.

But there’s always me. I’m always bringing me to the table.

You’re always bringing that possibility to the audience, too.

Yes. You can’t leave yourself out of the equation. I always am playing a character, but it has to start through me because how else can you make it personal? How else can you reach an audience? When we get cast in roles, we get cast for a reason. And for whatever reason in those roles you mentioned, the directors wanted my interpretation of the role. So why would I leave out my bag of tricks so to speak—who I am as an actor? That’s what they hired me for.

I’m also remembering your manipulator role in The Small Room at the Top of the Stairs.

Oh, my God, right?

He was really creepy, but I think now in retrospect what made him so interesting was what you’re talking about having brought to the role. Something shining through you that wouldn’t if you were more covered or more armored.

You’re not the first person who’s said he was creepy. But I thought he was charming, and I tried to amp up my charm a million percent dealing with my character’s wife, who I was so in love with. And the feedback I got was that what’s making him so creepy is that you are so sweet. You are so kind. But the things you are saying and doing, they belie the charm that you’re radiating.

The playwright Carole Fréchette said to me, “You were such a kind Henry, such a creepy Henry”—because she was used to seeing guys play it tough and overtly evil. But I said to the director Helen Murray, “You know I think his words are going to take care of that scary monster in the small room. So I don’t need to play into the idea of being that big and scary husband. I’m just going to be me. And I’m going to let the audience get it from the words and from my actions.” And they did. It served them in a different way than me going around banging my fists into walls.

That illuminated the character and brought us into the story in a subtextual way. With all the characters I’ve seen you play and how you’ve played them, the emotional freedom you bring to a performance is what seems to subliminally make the audience want to know you and be on your side.

In Wig Out! at Studio Theatre, I played this gay hypermasculine dude named Lucien. He did the most vile things, and he’s so calculated, but I tried to slide into that role with relaxation and charm. That was the first time I was ever in a show where the audience would boo me at curtain call. I think they were with me for the ride, but ultimately they could not condone the things that I did. And I thought, Well, I really must have taken them on a journey if they feel free enough to give me a boo.

In New Guidelines for Peaceful Times, you’re an actor playing a character who is an actor who we learn is in fact acting before our eyes. How do you think about playing all those layers?

It is such a chess match because I’m trying to charm this immigration officer and he’s really giving me nothing in return. I’m throwing at him: We share the same religion. I’m from a Catholic country, you’re from a Catholic country. Well, he was raised in a Lutheran orphanage. I throw at him a poem from his country’s most celebrated poet. He throws that back, Oh, yeah, I’ve heard of him. Isn’t he a writer?

I’m getting nowhere. I try to relate to his picture of his wife on his desk. It’s not his wife, it’s his sister. Everything I try is not working, so I have to pull out the big guns, I have to start acting, what I did every night for over 25 years. I start doing monologues and poetry. And he lays down the gauntlet and says: Makes me cry and I’ll sign your papers.

The horrific stories I tell are true, yet the immigration officer is unmoved by them. But when I step into the role of actor and give him fantasy, a monologue from a play, that’s what moves him. “That damn theater,” he says. That’s what gets him. And that’s when I realize there is something to be said for being an actor. I thought I was wasting my life in the theater every night. I missed what was happening in the world. But I wasn’t.

How did you find your character’s Polish accent?

I have to give a shout out to Leigh Dillon, who was my great speech teacher in college, at SUNY Purchase, Conservatory of Theatre Arts. She used to have her students sit underneath a glass living room coffee table and watch where the sounds lived in their mouths. She created the best speech technique, and I fell in love with speech and accents. With accents, she would always say, “Don’t listen to instructional videos. Listen to real speakers of the language.” One day I was home and this show came on about grannies who cook. It happened to be a Polish grandmother. I studied her. I listened to her on YouTube over and over again.

One of the questions the play asks is “Is there a place for theater in this world after the war,” meaning after World War II. What is your own view of the place for theater in the world today? And what makes you want to be part of it?

I don’t consider myself a very political person. I’m not as involved and as aware of politics as I really should be to be a responsible American in 2018. But the message of the playwright is so much bigger than I. I may not always completely get the message. I may not always be able to wrap my brain around their message. But I am a ready and willing vessel to deliver that message in the best way I can. I think that’s where the filter of Michael comes in and where I’m willing to let that message flow through me. Hopefully it reaches the audience in a way that not only lands on them but digs in the guts and moves a couple of things around. And hopefully when they walk away from the theater, when they get home that night and are about to turn off their phones and go to sleep, they’re still thinking about what they saw that night. And they’re somehow changed.

Running time: 60 minutes, with no intermission.

New Guidelines for Peaceful Times plays through October 28, 2018, at Spooky Action Theater, 1810 16th Street, NW, in Washington, DC. For tickets, call the box office at (202) 248-0301, or purchase them online.