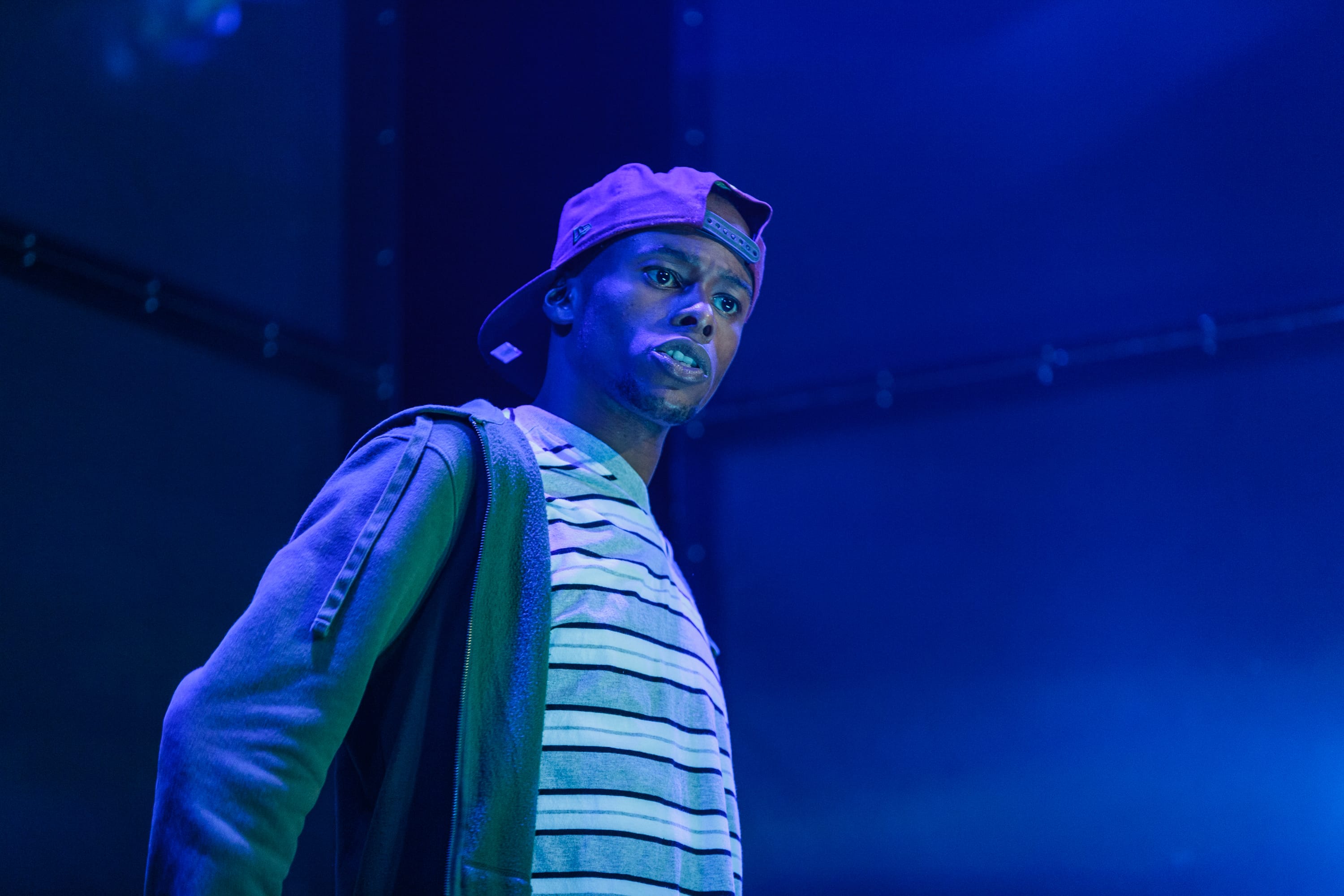

Long Way Down, adapted from the renowned young adult novel in verse by Jason Reynolds, is told in the voice of a 15-year-old named Will and performed by the prodigiously talented Justin Weaks. He is on stage alone for just over an hour. The story he tells is gripping, its content almost too unsettling for young adults. The other characters he evokes are vibrant and distinct; the poetic language he speaks is ablaze, as vivid as any I’ve heard on stage. Long Way Down in all its qualities is a one-act drama so good that grownup theatergoers could easily make it a hit. Yet here in Kennedy Center’s Family Theater there are young people, lots of them, accompanied by their parents, young readers, many clutching their copy of the book, mostly boys. And Weaks holds this whole intergenerational audience in the palms of his hands.

The book by Jason Reynolds was a New York Times best-seller, boasts a host of awards, and was a National Book Award finalist. Now having read it, inspired by this performance, I can see why. Written as a series of poems that pulse with sensation and narrative momentum, Long Way Down is propelled by Will’s grief over the shooting death of his older brother, Shawn, and his determination to follow the rule of revenge:

If someone you love

gets killed,find the person

who killedthem and

kill them.

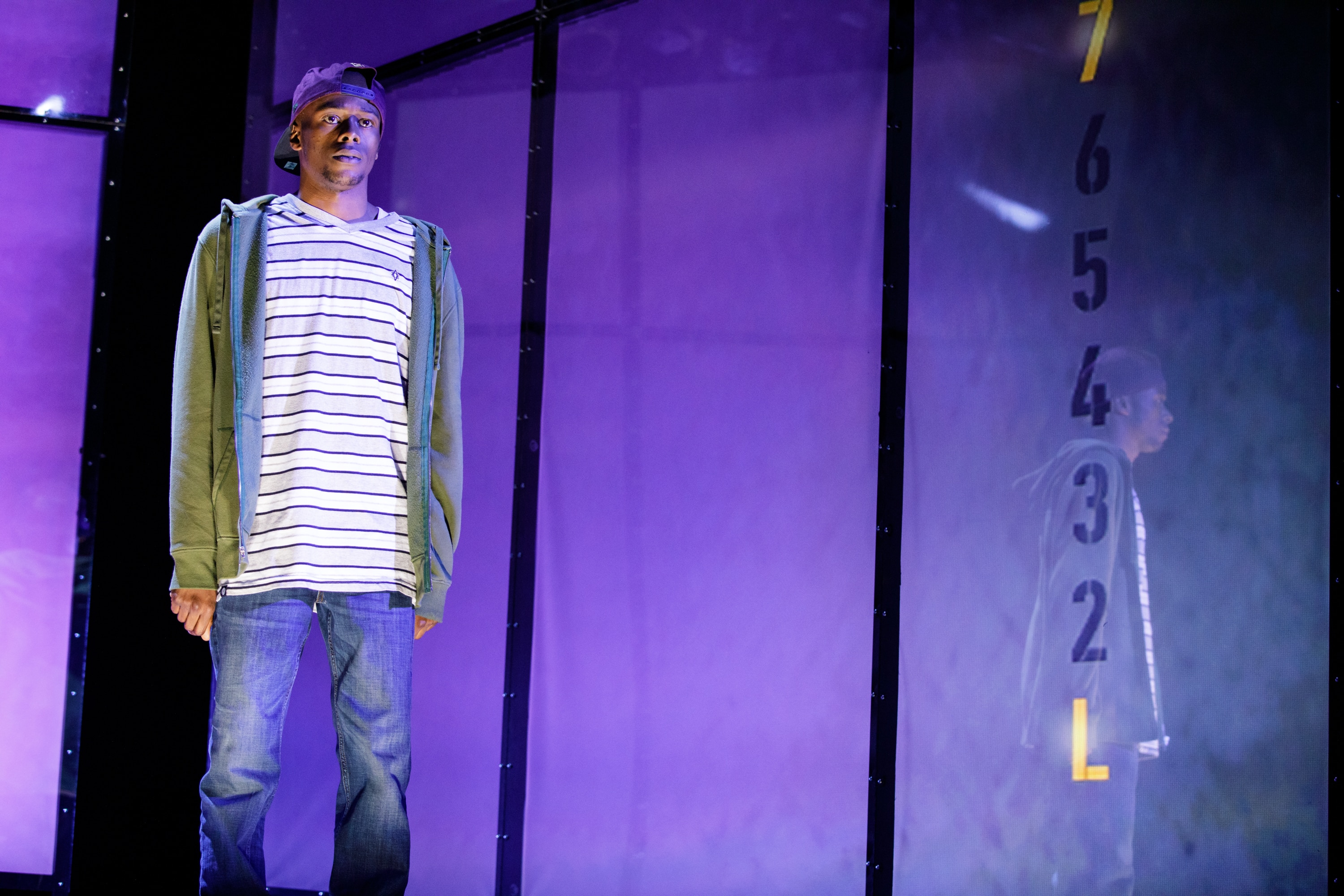

With intent to do the deed, Will finds the gun that was Shawn’s, tucks it into his waistband, and takes an elevator seven stories down to the lobby. It’s a ride that in real time would be a minute but in Long Way Down takes longer, because at each floor the elevator stops and another character from Will’s past gets in: his Uncle Buck, a girl named Dani he knew in grade school, his Uncle Mark, his Pop, Shawn’s friend Frick, and at last Shawn. They all congregate in the elevator in a haze of cigarette smoke, and they themselves are ethereal because they each died shot by a gun.

Weaks does not so much impersonate these spectral visitors as express who they are to Will, with a suggestion of a characteristic gesture here, a slight vocal alteration there. So we never lose sight of this lone man’s passage into memory and how remembering these dead people tests his will.

It is bravura solo storytelling.

The scenic design by Tony Cisek evokes the elevator interior with shiny, translucent panels that envelop the action and display, under William K. D’Eugenio’s animated lighting design, arresting projections designed by Michael Redman, including Will’s clever anagrams (canoe = ocean). Danielle Preston costumes Will in oversize streetwear that accentuates his youth and fragile agility. And Nick Hernandez amplifies the narrative with extraordinary music compositions and sound design, including samples from Shawn’s prized Tupac and Biggie.

Adapted for the stage with a fine ear for an actor’s presence by Martine Kei Green-Rogers, and directed with passion and precision by Timothy Douglas, Long Way Down is the world premiere of a project commissioned by The Kennedy Center. It is a hugely successful and satisfying production.

But curiously, except for the young people in the audience, I would have had no notion that Long Way Down was not a theater piece intended for adult sensibilities. Weaks as Will often addresses the audience personally, confidentially, never condescendingly, and always with the same naked honesty that I’ve seen him bring to roles in plays with mature themes. So as I left the theater I found myself wondering what it was about Long Way Down—both the source material and this stage adaptation—that connects so intimately to the lives of boys as young as 12.

And what I realized is this: Reynolds’s writing mines the inner emotions of his character’s mind with such veracity that it becomes a touchstone for feelings it is possible for a boy to have that are forbidden in his world where manly masks must be worn. Long Way Down is utterly unabashed about showing Will’s fear, insecurity, and vulnerability, and it is brutally realistic about the gendered expectations on him that he must live up to but isn’t sure he can. “No crying” is one of the rules Will believes he must obey. Will’s inner emotional life, which shines so clearly through Weaks’s transparent performance, becomes by extension an emotional universal: forbidden feelings of frailty Reynolds’ writing makes familiar, ownable, not to be suppressed, okay to be expressed.

Long Way Down is ultimately not so much a play about gun violence. It is about the violence done to one boy’s inner emotional life, and his coming of age in learning he need not fear feelings he is not supposed to have.

Running Time: 65 minutes, with no intermission.

Long Way Down plays through November 4, 2018, at The Kennedy Center’s Family Theater – 2700 F Street, NW, in Washington, DC. For tickets call the box office at (202) 467-4600, or toll-free at (800) 444-1324, or purchase them online.

LINK: “My Job Is to Crack Open My Soul”: A Q&A with Justin Weaks by John Stoltenberg

VIDEO: Jason Reynolds talks about his book Long Way Down (first a shorter version, then a longer version)