Update November 18, 2020: COVID cancelations to cost Kennedy Center over $80 million Scheduled performances through April 25 are off; Broadway musical tours are postponed; Kennedy Center Honors are shifted to spring.

About a month into the pandemic, Kris Funn was practicing his double bass “out of control,” with far more time on his hands than usual. Then, as reality set in that the crisis and its accompanying stage closures would last longer than anyone had imagined, the bassist did something for the first time in his jazz career: he put down his instrument. “You get really dark because you realize, I’m not going to be able to play out for months,” he said in an interview. The break only lasted about two weeks, but he’s now branched out into piano and electric bass.

With theaters shuttered for months, artists like Funn face hardship and a missing connection with live audiences. Some venues have taken cautious steps toward a comeback as restrictions have eased. After losing some $17,000 this year from scrapped tours that would have taken him as far as France and Indonesia, Funn finally got his first gig in October at the Kennedy Center. As part of a limited series of free outdoor concerts that begin at sunset, he played for an enthusiastic crowd spread across a limited seating area and the lawn further away. “You can practice all you want, but until it’s actual human beings and you have to react, it’s just not the same,” said Funn.

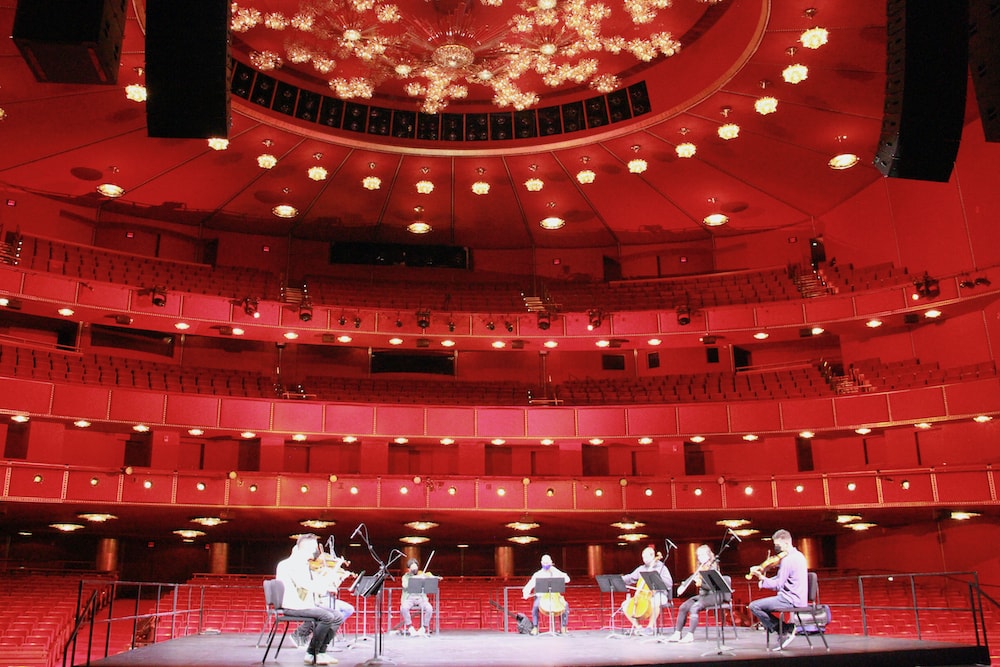

Indoors, the public can now purchase a seat on the stage of the Opera House, sitting six feet apart while facing the artists on a platform extension 30 feet away. But under Washington’s current restrictions, only 50 people can be seated for each event—less than 2 percent of the cavernous hall’s capacity—so tickets get snapped up within days. The unprecedented experience is both intimate and grandiose. Only a few dozen patrons share a view ordinarily reserved for performers, facing the plush hall decked in vibrant red and gold beneath a huge sunburst crystal chandelier gifted by Austria, contrasting with the stage’s poster-adorned wings. But the ingenious setup also highlights the pain and loss of the moment, as the audience stares at 2,364 empty seats.

It’s all part of a vision to “turn a negative into a positive,” said Robert van Leer, senior vice president of artistic planning. “The primary issue was safety—safety for the audience, safety for the artists, and safety for the crew and staff,” he said. The performing arts center worked “hand in glove” with the city, according to van Leer. A September 26 lyric showcase featuring Renée Fleming and Vanessa Williams marked its first live performance in six months. Jazz, hip-hop, and classical music offerings followed, prescient occasions as a new wave of the virus triggers new lockdowns and uncertainty around the globe.

The Kennedy Center is usually bustling with activity, hosting big crowds and an average of four ticketed events a day, or more than 2,000 performances, events, and exhibits a year. But only 13 performances have taken place since the modest reopening, five of which were reserved for frontline workers and their families. Another six public performances are scheduled for November and December.

In consultation with the Cleveland Clinic, the Kennedy Center developed elaborate health and safety protocols to make these shows a reality, from reducing restroom capacity to sanitizing makeup brushes and fogging the stage with disinfecting fluid. The center, which has helped set industry norms, follows federal guidelines as well as input from doctors and epidemiologists from the National Institutes of Health and George Washington University Hospital. Artists, crew, and staff members undergo testing, and a Theroscan touchless thermometer scans patrons’ wrists. In order to avoid confined spaces, the audience then enters the hall directly through the wide loading doors that open onto the front plaza. It’s through those same doors that Willie Nelson’s tour bus came on stage when he received the Kennedy Center Honors, the nation’s highest artistic achievement award, in 1998.

While daunting, all the extra precautions are necessary to “maintain the flame of live performance in whatever way we can,” van Leer said. And after so many months of silence, the public is thirsty for live music, dance, and theater. “I didn’t realize how much I really needed it and missed it,” said Victoria Ford, a concert photographer who came to Funn’s performance with friends. “Hearing the music was really touching to the soul. It was awesome just to hear it again and not watch a livestream, because I’m so tired of livestreams.”

The Washington National Opera brought its Cafritz Young Artists to public parks, farmers markets, and medical centers in October as part of a pop-up truck mini-tour set to relaunch in the spring. In a modified version of the National Symphony Orchestra’s popular In Your Neighborhood series, select musicians are performing primarily for health care workers at more than 30 hospitals, assisted living facilities and other sites from September to November. Kennedy Center Opera House musicians, meanwhile, have performed in neighborhood porch concerts, at the George Washington University Hospital and at Miriam’s Kitchen during their dinner service for the homeless.

Among the select artists performing at the Opera House were the award-winning Dover and Escher quartets, playing jointly on October 20 in the largest formation currently allowed on the stage extension. “It’s perhaps the only date on our calendar in the fall that never wavered,” Escher Quartet cellist Brook Speltz said after listing a slew of “heart-wrenching” cancellations reaching deep into next year. “To be able to play in the Opera House, that’s a once-in-a-lifetime experience, especially at the Kennedy Center, so I think we’re going to cherish that for a long time.”

Neither quartet had performed indoors for a live audience since March. The 30-something musicians played two pieces by composers who were only teenagers when they put pen to paper: Felix Mendelsohn’s sunny Octet in E-flat major, Op. 20 and George Enescu’s Octet in C major, Op. 7, written nearly a century later, in 1900, and bursting with polyphonic energy but indebted to the late Romantic era. In order to mimic the sound bouncing off of wood paneling in a traditional setup, master technician Dustin Dunsmore deliberately caused a slight delay in the speaker feed as he calibrated the audio. It worked. The tone was as warm and lush as the setting.

Following safety guidelines also meant that the musicians sat much farther apart than usual, complicating their ability to precisely hear and respond to one another. “If you’re only going off aural cues, you’re going to be late. So you have to try to use visual cues to keep all eight people together,” Speltz explained. “It was definitely a unique challenge for that evening. But in the end, it was all made up by the gratification of hearing applause after you performed, which for so many months, you just didn’t get.”

During the many livestreams in which he participated, Speltz noted that “you maybe knew people were watching but you had no way to gauge their emotional response to what you were doing.” There have been nearly 1,500 views of Speltz’s April 4 performance for the online platform Groupmuse with his wife Milena Pajaro-van de Stadt—the Dover Quartet’s violist—and his violinist brother and fellow Escher Quartet member Brendan. Between performances for digital platforms, limited outdoor engagements, and teaching, Speltz said the quartet has managed to stay afloat.

Like Funn, Speltz stopped playing as the pandemic began to peak—for the first time since starting on the cello at the age of five. “After three to four weeks, I tried to pick up the cello and practice, but I just couldn’t do it,” he said. “I just didn’t have the energy or the desire to even hear it.” It was the promise of a new performance opportunity for him and other members of the Escher Quartet that jolted Speltz back into his practice routine after more than a month away from the instrument.

In order to defray the costs associated with putting on the Opera House shows for such small audiences with extensive precautionary measures, the Kennedy Center is building on existing artistic relationships to develop a viable approach in changing circumstances, van Leer stressed. “We are working with artists who want to be on stage, who want to perform, and finding a way forward for our business model in these challenging times,” he said. “We have not been working to the norms of the past. The fees that artists are taking are not like what they would normally take in a non-COVID world.”

As with so many major performance halls all over the world, the pandemic has had a brutal toll on the Kennedy Center, for which ticketing income usually makes up about 70 percent of the budget. More than 1,116 events were canceled for the 2019–2020 season that ended in August, including ticketed performances, free activities, and rentals. The unexpected shutdown led to some $83.9 million in revenue losses, a figure estimated at more than $50 million for the 2020–2021 season. More broadly, such closures have major ripple effects across the U.S. economy, to which the arts contribute some $877.8 billion, or 4.5 percent of GDP, five times more than the agricultural sector.

In addition to individual donor support, the Kennedy Center received $25 million in federal emergency funding, most of which went to staff compensation and benefits, as well as pandemic-related safety contracts, supplies, and cleaning. The live events also come fraught with potential legal risk. The arts complex protects itself legally by working “closely” with its in-house attorneys, a spokesperson said.

Some of the on-stage performances are available on digital platforms to watch from home, while other content has been created specifically for online consumption. For classical music in particular, it’s a lasting legacy of this otherwise painful era that has fostered innovative initiatives elsewhere, like cellist Jan Vogler’s Dreamstage livestreaming platform or violinist Daniel Hope’s Hope@Home series, which in its latest iteration presents emerging freelance musicians from his living room.

The focus on digital offerings, driven for now by necessity, is a “game changer,” van Leer stressed. “Now, in many ways, it’s an artistic space in its own right. The big change is the integration of the digital sphere into the broader artistic landscape. It’s a hybrid of the two in many ways in terms of how those worlds come together.” In that vein, the Kennedy Center has collaborated with arts organizations across the United States to present 20 weeks of free, live programming viewable online.

The changing circumstances have nonetheless led some artists to weigh difficult decisions. “I’ve had some interesting thoughts. Things aren’t going to be the same,” said Funn, half-jokingly excusing himself for rambling since he’s only spoken with his wife for the past seven months. If it weren’t for his savings, he added, “I don’t know what I’d be doing right now—probably driving an Amazon truck or something.”

When the Escher Quartet first got back together in June after their last pre-pandemic performance in Miami on March 11, the musicians played at the Speltz family’s isolated mountain cabin in Idyllwild, California, after they all tested negative for the coronavirus. They immediately launched into Beethoven’s “Harp” String Quartet in E flat major, Op. 74, which begins serenely before moving on to dramatic nods at his Fifth Symphony and ending with a gentle theme and variations.

“I don’t think any of us had been so excited to get together for many years,” Speltz recalled. “To be able to sit down and play music just for the sake of playing music…that was very powerful for us. In some ways, it reconfirmed our desire to be a quartet and pursue this art form in the face of the greatest uncertainty in the industry this century.”

SEE ALSO: Vanessa Williams and Renée Fleming sing in a new era at the Kennedy Center by Darby DeJarnette