If you went looking for faces that can express the tragicomic interior of Samuel Beckett’s stark and minimalist storytelling, you would want to choose those of Kim Curtis and Ron Litman, the actors who each anchor two playlets in Scena Theatre’s transfixing Beckett Shorts. Even when Becket’s text is silent, their visages speak volumes. Even as Beckett’s text seeks to hold the absurdity of existence up to objective view, Curtis and Litman put a human face on it and make it relatable. And especially in the intimate black box at DC Arts Center, their every up-close eloquent expression reminds us of the power of in-person performance to pull us in.

The 80-minute anthology of four short dark comedies, directed by Scena Artistic Director Robert McNamara, is like a quick visit to Beckettville. McNamara, who knows his way around there, guides us on a tour-bus overview of the renowned Irish playwright’s themes and stylistic techniques, which have influenced avant-garde theater makers for decades. It’s an exhilarating trip well worth taking.

The audience I saw the show with was rapt, often chuckling in amusement. Or maybe bemusement. With Beckett, you never know. When you enter into his slightly askew worldview — which watching Scena’s skilled production will make quite likely — you may find yourself ruminating not only on what is going on but on why anyone goes on at all.

That question of the mortality option is one that Beckett kept coming back to, and it shows up explicitly in the third playlet, Rough for Theater I, where two unnamed characters basically banter. Like many a character in Beckett’s work, they are aged, impaired, and confined — that is to say, metaphorically alienated in some way. One of them, called A in the script, is a blind beggar; the other, B, has only one leg and uses a chair. There comes a moment between them that seems the perfect synecdoche for Beckettian wit and weltschmerz:

B: Why don’t you let yourself die?

A: I have thought of it.

B: [Irritated] But you don’t do it!

A: I’m not unhappy enough.

How can one not laugh at death on a line like that?

Central to Beckett’s theatrics is the clown — the Keatonesque, Chaplineque jester who transmogrifies existential angst into physical comedy — and Beckett Shorts begins with two classic examples: Act Without Words I and Act Without Words II, which are written, exactly as the titles say, in the form of extended narrative stage directions uninterrupted by speech.

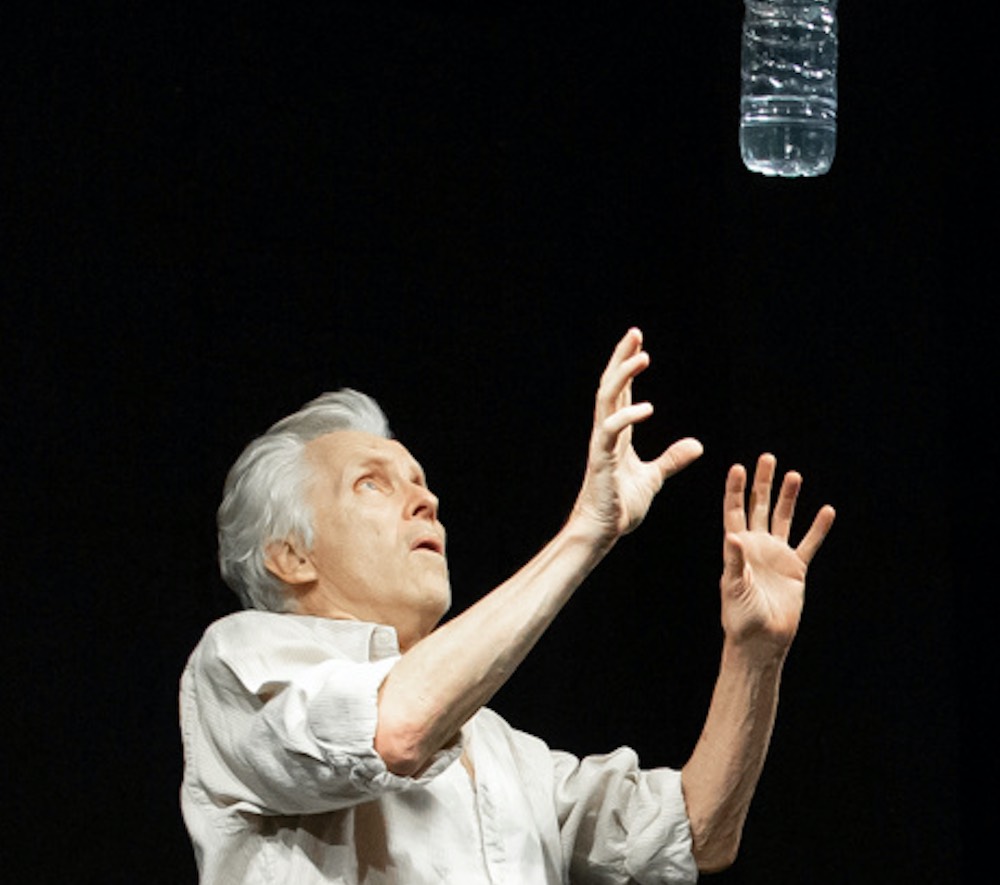

In Act Without Words I, Kim Curtis gets thrown onto the stage as a loose-limbed mime who keeps being frustrated by an out-of-reach water bottle even as he keeps being perplexed by the appearance of nonsensical objects: a tree whose foliage is an umbrella, an oversize scissors, a knotted rope. He tries to stack big wooden blocks so he can climb high enough to get the water bottle, but funnily enough, he keeps failing. Now and then Curtis looks to the audience with a wry smile that seems like a non sequitur but that actually plays like a joke. Or sometimes he’ll look to the audience blankly as if to say: Can you believe this? Thus for us the audience it is his knowing face that becomes our throughline of recognition.

Onstage in Act Without Words II are two white mounds that turn out to be humans wrapped in muslin bedding. A black-clad figure enters with a pointing hand on a pole and pokes one of the mounds and out crawls Kim Curtis wearing no pants. He arduously dons a baggy suit, boots, and bowler, seeming to droop in his body and sag in his waggish face; then he awkwardly removes the clothing and crawls back under muslin. The suit-up/disrobe routine repeats with a bit more braggadocio by the person in the other mound, Lee Ordeman. But it is Curtis’ wry smile and look of disappointment and discouragement that is our portal into the play’s open-to-interpretation point.

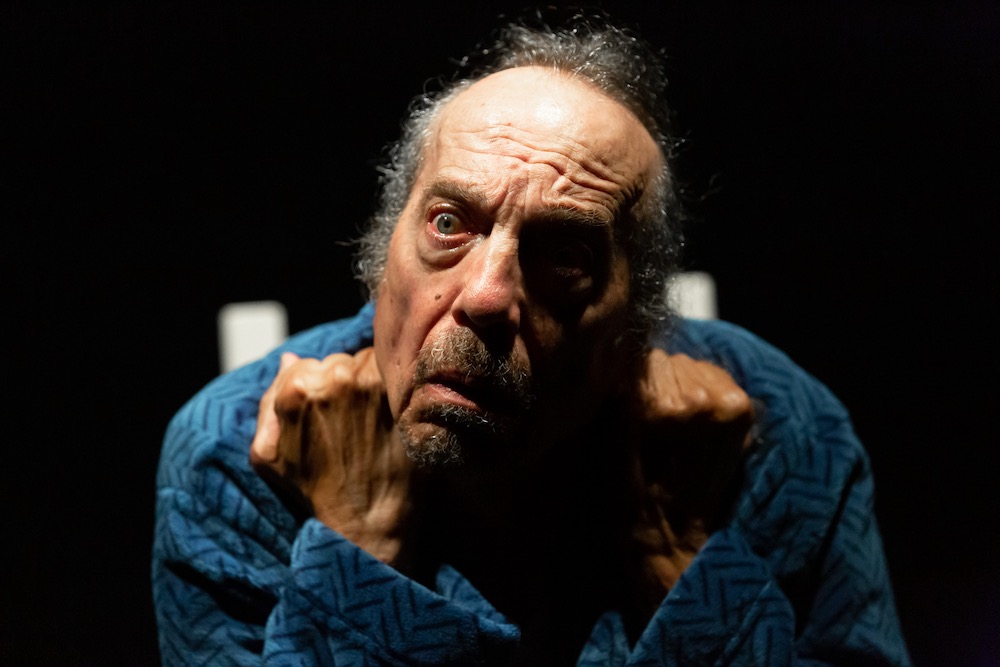

With the third playlet, Rough for Theatre I, there are words, actual dialog, bandied back and forth by two remarkable actors. Ron Litman is A, a blind man sawing away on a toy fiddle, and Buck O’Leary is B, with a blanket in his lame lap and a resonant voice that could rouse the dead. There are slices of silence between their lines, but not the kind you get when cues are not picked up. Instead, those mini hesitations seem a rhythm of reluctance on the brink of a terminus. Little caesuras before cessation. A calls B “Billy,” after his son. They prattle on about this and that. They make elliptical reference to caretaking women who once sustained their lives. Meanwhile, Litman brings a hangdog look of desperation to the role such that his face says far more to us than the cryptic script.

In the fourth playlet, Eh Joe, a piece written for British television, we experience the full force of Litman’s face as he listens to the recorded voice of a woman with whom he was once in a relationship. We never see her but Litman as Joe sure does: In his haunted, unblinking face we can read exactly what he is remembering, thinking, feeling. She is low-key but insistent. She seems to be chiding him, upbraiding him.

You know that penny farthing hell you call your mind . . . .

That’s where you think this is coming from, don’t you?

. . .

Anyone living love you now, Joe? . . .

Anyone living sorry for you now?

Stacy Whittle’s acting as the voice was flawless, but the playback at the performance I attended was too quiet to make out much of what the character was saying. Nonetheless, we had Litman’s fluent face to fill us in. Do we see his fear, his grief, his guilt, his anger, his existential angst? Probably all that and more.

Welcome to Beckettville. Enjoy your stay.

Running Time: Approximately 80 minutes, with no intermission.

Beckett Shorts plays through July 16, 2022, presented by Scena Theatre performing at the DC Arts Center, 2438 18th St. NW, Washington, DC. Purchase tickets ($35 adults, $28 DCAC members) online.

COVID Safety: Masks are optional. No vaccination status required.

Performance Schedule:

July 1, 7:30 pm (Fri.)

July 2, 7:30 pm (Sat.)

July 3, 3:00 pm (Sun. MATINEE)

July 6, 7:30 pm (Wed.)

July 8, 10:00 pm (Fri.)

July 9, 3:00 pm (Sat. MATINEE)

July 9, 10:00 pm (Sat.)

July 13, 7:30 pm (Wed.)

July 15, 10:00 pm (Fri.)

July 16, 300 pm (Sat. MATINEE)

July 16, 10:00 pm (Sat.)

Actors: Kim Curtis, Lee Ordeman, Buck O’Leary, Ron Litman, and Stacy Whittle. U/S: Ellie Nicoll and David Johnson.

Designers: Robert McNamara (Artistic Director), Denise Rose (Sound Design), Marianne Meadows (Lighting Designer), Carl Gudenius (Set Designer), Carolan Corcoran (Costume Designer), Paul Gallagher (Fight Director), Laura Schlachtmeyer (Stage Manager), Cate Brewer (Assistant Director)

Staff: Gabriele Jakobi (Dramaturg), Dean Creative (Marketing), Peggy Kearns Dean (Public Relations), Anne Nottage (Literary Manager), Barbara Weber (Business Advisor), Paul Hastings LLC (Attorneys), Haines & Lagerquist LLC (Accountants), Natalia Nagy and Colin Davies (Literary Board)

SEE ALSO:

Scena Theatre to present four black comedies by Samuel Beckett (news story June 2, 2022)