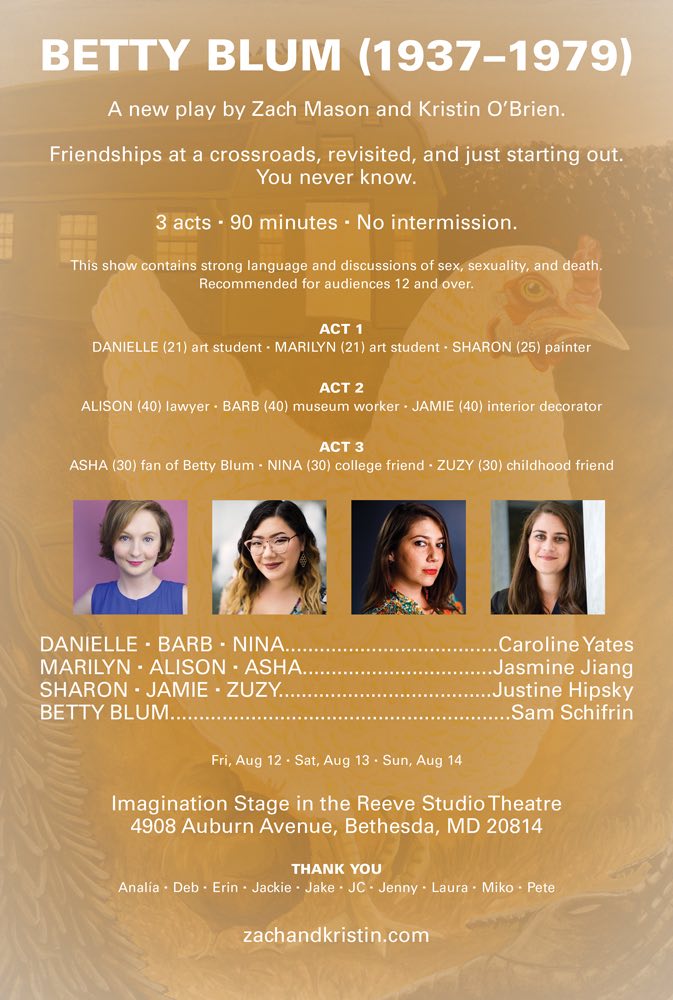

A painting of a chicken backlit in the golden hues of the Dutch masters is the sole set piece in the black box theater — save for an upholstered bench. This chicken and its fictionalized painter’s difficult life become the throughline for writing pair Zach Mason and Kristin O’Brien’s newest play, Betty Blum (1937-1979), which premiered at Imagination Stage’s Reeve Studio Theatre in Bethesda from August 12 to 14, 2022.

Mason and O’Brien tested their chops in the improv comedy sketch world, including at DC’s own WIT — Washington Improv Theater — and while there are funny moments in Betty Blum, this triptych featuring three mini-playlets is not all laughs. Covering three specific late-20th- and early and current 21st-century eras, the three actors take on three distinctive characters, one in each scene. And while there are laugh-out-loud moments, some just goofball funny, others satiric with a bite, Betty Blum leaves us pondering what mid-20th-century social critic Betty Friedan called “the problem that has no name.”

Blum’s life as a mid-20th-century contemporary artist serves as the connective tissue in the play. Her experience as a painter is instructive of the toll the male-dominated art world takes on female artists. While Blum is not seen, she is heard in voiceovers, featuring Sam Schifrin, and her life is recounted first bitterly via her adult daughter, Sharon, played by Justine Hipsky with a prickly know-it-all exterior, but a vulnerable, even broken core. Then later, others who only know her legend discuss Blum’s life, art, and legacy.

Each act is set in a city art gallery where the aforementioned chicken portrait has pride of place. We first meet two starry-eyed art students, Danielle and Marilyn, on a class trip to an art gallery for Blum’s posthumous show. Wide-eyed, perhaps, naïve, these friends encounter Blum’s daughter and learn a truth about a woman painter working in the hyper-masculine, muscular downtown art scene of the 1950s and ’60s. Slinging back a chardonnay, Blum’s daughter overshares about being a neglected child, left alone in dingy New York apartments, or roaming a commune, while her mom pursued an art career. “You understand,” Sharon said to assuage the wide-eyed acolytes, “this is about one mother who did a bad job.” Each proceeds to dig up childhood pains and family dysfunctions, until one finally asks the bitter daughter, “What saved you?” “Nothing,” she replied. She, too, has an unsuccessful art career; “derivative naturalism” she scoffs at it.

Act II reunites two high school friends, 20 years after graduation and distancing. As Alison, Jasmine Jiang exudes success and nervous anticipation, clad in her peplum suit jacket and working mom skirt and low-heeled pumps. She uses her purse as a security blanket, picking it up, holding it against her chest like armor against the barbs her once BFF Jaime slings. The two meet at the same gallery, because Alison’s mother collected some of Blum’s early works — pre-chicken, that is. Seeing each other for the first time as adults, they share never stated hurts, jealousies, and disappointments. Jaime (Hipsky, this time in overalls, a messy ponytail, and a backpack) was the theater kid, who grew up in a lower-middle-class household, observing her friend’s privileges. These days she writes plays for a local community theater. Alison, a successful lawyer and mom, carries her own hurt — she lost her mother as a teenager, and couldn’t keep up with the theater crowd. Their conversation is strained, fraught with tension, and unfulfilled expectations of what female friendships should be. Each has let blame, disappointment, and feelings of abandonment fester. A young, kooky gallerist (here Caroline Yates as a kooky bubbly blonde) interrupts, assuming the pair are on a first date.

The third act and third canvas depicting female relationships features Asha — here Jiang as studious party girl Jiang — convening a meeting of her two best friends, nervous Nina (Yates) and sharp-tongued Zuzy (Hipsky). Asha selected the appointed spot, in front of the Blum painting, because a recently published biography of the artist inspired her. Here the chicken and Blum’s now-legendary life become a takeoff point for discussions of career problems, parent problems, and man problems. A sense of both competition and camaraderie infuses the scene, and incidents of Blum’s life discussed earlier return, bringing her history full circle.

It can’t be an accident that playwrights Mason and O’Brien chose the name Betty, channeling or nodding to proto-feminist Betty Friedan. As well, they allow their Betty to tell her own story during the entr’actes in Schifrin’s smoke-and-whiskey, no-nonsense voice. “My name is Betty Blum. Men have dominated the art space for centuries,” Blum said, using animals to represent their masculinity. Thus, is that chicken a tweak or a dig at the male-centric art world? No matter, because Betty is direct and succinct: It’s a necessity to paint … I want to work and enjoy the work without having to settle down with a man or win approval of a man.

Blum serves as the bold brushstroke holding each of these disparate scenes together. Her life — though fiction — remains instructive about the ongoing struggles women face in making a place for themselves, finding satisfaction in what they do and how they choose to live their lives. Blum was an outsider, a painter, single-minded and free-spirited during her lifetime and in her afterlife. She serves as an example of the nameless problem that Friedan tried to articulate in her groundbreaking 1962 book. Yet, 60 years later, women still struggle to find their own identities and connect with other women in what remains a man’s world. Or as Zuzy said, “It’s impossible to be a woman in any decade.” Indeed.

Betty Blum (1937-1979) played August 12, 13, and 14, 2022, presented by Zach Mason and Kristin O’Brien performing at Imagination Stage, 4908 Auburn Avenue, Bethesda, MD.