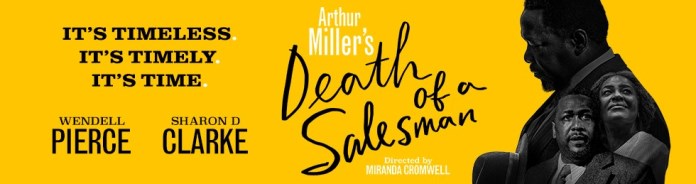

Playwright Arthur Miller’s original working title for his 1949 American classic Death of a Salesman (recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for Drama and six Tonys, including Best Play) was “The Inside of his Head” – and that’s precisely where the electrifying Broadway transfer of the acclaimed Olivier Award-winning London revival takes us: into the disturbed and rapidly deteriorating mind of protagonist Willy Loman. Directed by Miranda Cromwell (who co-directed with Marianne Elliott in London and shared the Olivier for Best Direction of a Play), the two-act tragedy is seen here, for the first time on the Broadway stage, from the perspective of a Black family. It underscores the universality of Miller’s “everyman” story, while enriching it with resonant racial overtones of the Black experience in America, as delivered by a superb cast led by Wendell Pierce and Sharon D Clarke, who also starred in the London production.

Set in Brooklyn in 1949, the heartrending narrative is conceived in the format of a memory play, jumping back and forth in time with key episodes and people from the past flooding Loman’s brain in its present unbalanced state and revealing the dramatic loss of his grip on reality. It’s an explosive mental decline exacerbated by anger, guilt, and shame over his steadily dwindling sales and income, infidelity to his loving and supportive wife Linda, broken relationships with his underachieving sons Biff and Happy, dismissal by his imperious second-generation employer Howard, and all the lies he tried to sell them, and himself, in his failed quest to achieve the American Dream of material gain and social status.

In contrast with the realistic period costumes by Fleischle and Sarita Fellows and hair and wig design by Nikiya Mathis, Loman’s fractured thoughts are echoed in the show’s abstracted surreal set design (by Anna Fleischle), lighting (by Jen Schriever), and sound (by Mikaal Sulaiman), which signal the incessant montage of haunting recollections of his hoped for opportunity, respect, and success that eluded him, pervaded his unfulfilled life, and drive him to his devastating end, as does his imagined conversation with the apparition of his deceased elder brother Ben (the commanding André De Shields, in a dazzling white suit, sparkling silver shoes, and gems that conjure the wealth he attained, and Willy craves, in the diamond trade).

All the psychological and emotional anguish is delivered in the revelatory portrayals of Pierce and Clarke, reprising their roles as the unstable self-deluding Willy, who darts erratically between optimism and frustration, internalized pain and rage, desperation and delusion, and the devoted Linda, who manages their difficult finances, sees him as “a good man” despite his flaws, continues to love and to worry about him, and advises her sons that “Attention must be paid” to their troubled father and the value of his life, in a deeply moving performance brimming with strength, dignity, and commitment, empathy and pathos.

The stellar leads are given outstanding support by Khris Davis as Biff, a popular high-school football star with a promising future, turned vulnerable drifter who forsakes the life his cheating father wants for him in favor of the beauty and quietude of farming and working with his hands; and McKinley Belcher III as Happy, who was ignored by Willy from a young age in favor of Biff, but more closely follows his example, becoming a cheerful womanizer, ambitiously overselling his achievements and Biff’s to impress, and always willing to tell his parents what they want to hear, whether or not it’s true. Their scenes of brotherly bonding (especially upbeat and funny in their animated conversation in their childhood bedroom) is as heartwarming as Willy’s paternal disappointment in them is gut-wrenching.

The remaining characters and their actions assume new meaning and significance with the production’s Black re-envisioning of the Lomans. Delaney Williams as Charley, a white business owner and Willy’s concerned and steadfast next-door neighbor, visits him and plays cards, generously provides money when asked, offers him a much-needed job that he turns down, and proves time and time again to be a real friend. Stephen Stocking as Charley’s son Bernard, a schoolmate and playmate of the Loman boys, makes the transition from studious child who idolizes Biff, to accomplished lawyer who inspires Willy’s jealousy over what his own sons didn’t attain. Both are the only ones besides Linda, Biff, and Happy to attend his funeral and to mourn his loss, but here they also embody the unspoken advantages of being white, to prosper in a predominantly white stratified society.

Other scenes and interactions also take on overtones of race, in addition to class. When Happy and Biff make plans to treat Willy to dinner at a high-end restaurant, the white waiter Stanley (played by Blake DeLong), who knows Happy, moves them to a back table, leaving us to wonder if it’s to give them more privacy or to keep them out of view and apart from the other affluent patrons. When the teenage Biff knocks unexpectedly on the door of Willy’s hotel room, he wants to avoid his son seeing The Woman he’s having an affair with (portrayed by Lynn Hawley and characterized with an irritating and unappealing laugh in his unhinged guilt-ridden flashbacks), so tells her to hide because being there together might be illegal (implicitly not just because of their extra-marital assignation, but because she’s white). And the segment in which Willy is demeaned by his supercilious young boss Howard (played with chilling disrespect by DeLong), who drops his lighter, has Loman bend to pick it and light his cigarette, then callously dismisses him from his office and his employment, elicited audible gasps from the audience at the performance I attended (and, one would expect, at every performance).

Rounding out the compelling company are Chelsea Lee Williams as Miss Forsythe and Grace Porter as Letta/Jazz Singer – women the Loman brothers meet at the restaurant and with whom they exit, disavowing Willy and leaving him alone and distraught. Along with the jazz stylings of Porter, the play, with John Miller serving as music coordinator and Femi Temowo as composer, includes emotive numbers in the traditional African American genres of blues and gospel, which further express the profound feelings of the characters.

This distinctive revival of Miller’s insightful classic brings new life and relevance to his familiar story, with must-see performances by a top-notch cast. It’s on Broadway for a strictly limited engagement through mid-January, so be sure to get your tickets while you can. If you’d like to get more background on the world of the play, visit the show’s website for an informative study guide that’s useful for students and adults alike.

Running Time: Approximately three hours and five minutes, including an intermission.

Death of a Salesman plays through Sunday, January 15, 2023, at the Hudson Theatre, 141 West 44th Street, NYC. For tickets (priced at $70-347), call (855) 801-5876, or go online.