Renowned playwright Pearl Cleage is also an essayist, novelist, poet, and political activist. Known for such works as Blues for an Alabama Sky, Flyin’ West, and Angry, Raucous, and Shamelessly Gorgeous, Cleage has explored social issues throughout the years with unflinching honesty and care. “The purpose of my writing, often, is to express the point where racism and sexism meet,” says Cleage. Her first novel, What Looks Like Crazy on an Ordinary Day, was an Oprah Book Club selection and a New York Times bestseller.

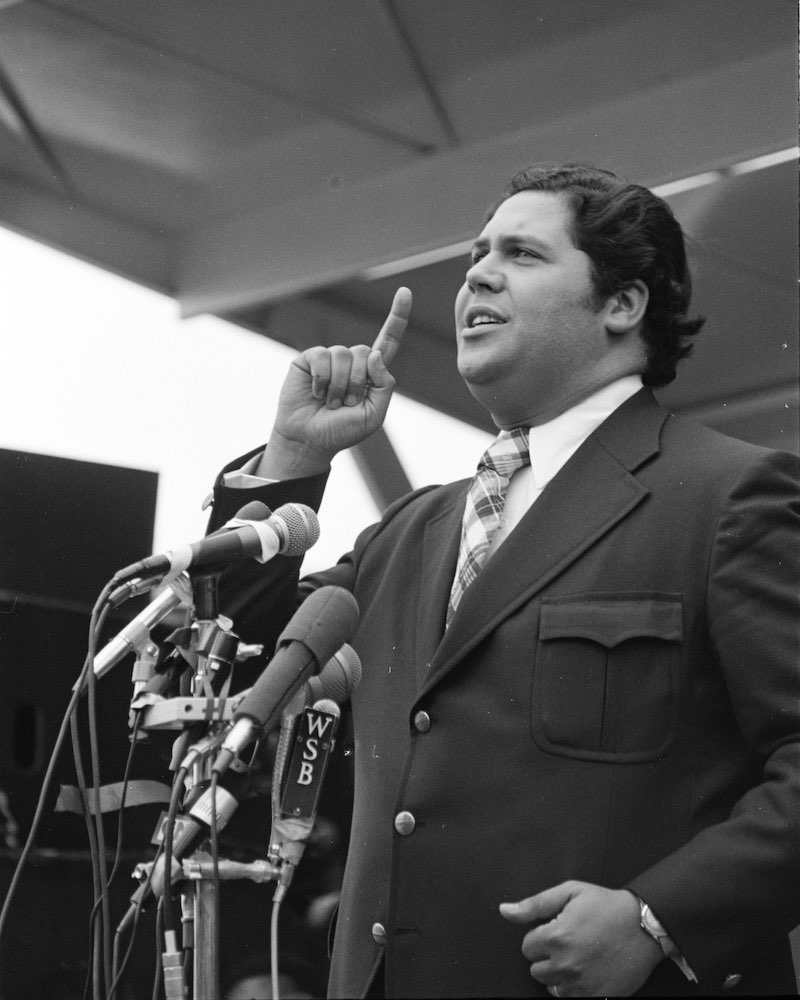

Her new play, Something Moving: A Meditation on Maynard, which runs September 22 to October 15 at Ford’s Theatre, is a reflection on Maynard Jackson, Atlanta’s first Black mayor, who was elected in 1973 and started his first term the following year. Per the Ford’s announcement,

Cleage sets the play in present-day Atlanta, but soon the story travels back 50 years as citizens of the city recollect and reflect upon the significance of the once-in-a-lifetime election that turned Atlanta into a progressive example of the New South. Cleage’s unique theatrical voice turns Atlanta into a full-blooded character while allowing her audience to feel what it was like to be part of a true historic moment in the Southern capital city.

Something Moving helps to mark the 50th anniversary of Jackson’s election, which ushered in a fresh new approach to hope, politics, and national possibilities. This premiere production is part of Ford’s Legacy Commissions program, which I reported on in February. Cleage (pronounced “cleg”) is based in Atlanta, Georgia, where she is Distinguished Artist in Residence at the Alliance Theatre. I recently had a chance to talk with her about her current project and why she remains optimistic in these tumultuous times.

Debbie Jackson: You indicated that you’ve been journaling for years, even as a little girl, exploring aspects of living in the world and your life. You’ve shared that it’s your way of processing life and events and that you have mounds of journals over the years, including from when you were press secretary and speech writer for Maynard Jackson in the 1970s. How did all your notes come together to create this piece?

Pearl Cleage: Yes, I have a trove of journals of all kinds I’ve been writing over the years. The journal entries helped me go back in time to remember and relive the scenes and the moments. The characters in Something Moving are all fictional, of course, and not based on specific people, but are instead fully imagined and created from the voices in my head.

Why did you write Something Moving: A Mediation on Maynard? And why now?

I wanted to create a piece that allowed us to think about and remember what the election felt like, beyond the surface details — beyond how many votes did he get, jobs and programs promised, factual things you can find in a reference book. For me, it was about being swept up in the campaign and the movement of the people that made it happen, how exciting it was to be there. So many different kinds of people came together because we all saw something special and exciting in Maynard Jackson. He encompassed, represented, and included us all like no other political leader ever did. Everybody’s excitement seeped into my imagination and characters flowed and developed from there. Maynard Jackson was a bigger-than-life kind of person and personality. You couldn’t help but be touched by the passion of what he was doing and his mission. He was brilliant, charismatic, and also committed to his vision.

There’s been a confluence of massive socio-political shifts over the last 15 years since the election of Barack Obama in 2008, then the 2016 backlash, and the murder of George Floyd and the pandemic in 2020 — did these events impact your mission and writing efforts?

Certainly, all of those events had a direct impact on me, on all of us. With everything that’s happened, I want us to remember how different we felt about politics back then, about the identity of this country. I wanted to portray the excitement of a world that people might not even remember, but it’s important that they do. That’s a primary reason for this piece to come now in this moment, because so many people, young people especially, are very cynical about politics, about voting. The best tool that citizens have to make their voices heard is voting. Your elected leaders and officials are determining your lives every day. And now there’s even more urgency with politics seeping directly into the education system and elected school boards. Some of them are censoring the books and writings that we took for granted would be available to young people.

Looking back on your own early stages, you were doing spoken word and poetry and writing books in the 1970s. How did you pivot into such an intense political scene, into the heat of such a nationally significant campaign?

Actually, I was raised with an orientation to politics. My father, Reverend Albert Cleage, founded the Pan African Orthodox Christian Church, also known as the Shrine of the Black Madonna in Detroit where I grew up. My family started a weekly Freedom Now Party newspaper, my dad ran for governor, and there was constant community activism in my life, so I was steeped in the mechanics of getting the word out, handing out leaflets, being part of rallies. My family was dedicated to the freedom struggle. So campaigning came natural to me, speech writing, energizing the crowd, getting citizens involved — those were my strengths I used in campaigning for Maynard Jackson, and it was all particularly exciting when we won!

You mention the term “citizen” — that’s a crucial aspect of the play because nine of the characters are identified as Citizens, and while they all allude to and refer to Maynard Jackson, no one is cast as Maynard. This is an unusual structure, to ruminate on aspects of a main character indirectly through others. How did this unique structure come about?

Well, we’ve seen shows where important people are portrayed, but we don’t see or hear from the people around them on the periphery who are not presented as important or significant. I wanted a different structure, and instead of presenting Maynard Jackson as a character, we get a chance to look at fictional people around him who are bouncing off of and contributing to his energy and effectiveness, and we’re learning about Maynard from their perspectives. When you think about it, we bring attributes to the “important” people we think we know and make a lot of assumptions about them. Maynard Jackson didn’t achieve his monumental accomplishments by himself. He energized people so they could appreciate their own power. We can become part of the story. That’s so important especially now that we’ve become so isolated since the pandemic. What theater does better than anything else is bring people together in a community and tell a story. That’s what I want to happen with this piece.

Also, I’ve actually used this format for some of my other works, Blues for an Alabama Sky, for example, where the characters talk about real people — Langston Hughes, Adam Clayton Powell. This gave me the freedom to create characters in famous peoples’ lives. Who were their friends, who did they talk to and confide in? This opens up new points of view to learn about people we think we already know.

How did this piece end up at Ford’s Theatre?

It all started when Ford’s Theatre under the visionary leadership of Paul R. Tetreault developed The Ford’s Theatre Legacy Commissions, where they commissioned playwrights across the country to shine a light on historical figures they thought hadn’t gotten the attention they deserved. The Ford’s Theatre Legacy Commissions granted total freedom as to how you wanted to tell the story to encourage the creativity of contemporary playwrights to present their take on aspects of American history. I had just started thinking about the fact that it will soon be 50 years since Maynard’s election as the first Black mayor of Atlanta. So I submitted my premise and was selected to receive a commission as one of the cadre of playwrights for this project.

And of course, I knew about Ford’s Theatre, the history and what happened there, but there’s simply nothing like being on that stage to understand how important President Abraham Lincoln was at such a crucial time in American history. Talking about Lincoln, you’re talking about the American story. You can feel his spirit at that theater, you really can. And I still marvel that the last night of his life, he went to the theater! And the insane madman that shot him was an actor! There’s so much theater tied up in those final moments, like how could it possibly be true, but it was. When we’re on that stage, looking up at that box seat with the bunting on it makes it all so present, so real, that this was a living breathing person. So the idea of having a play in that hallowed space, I’m so honored and feel deeply the spiritual significance of being allowed to work there.

What would you like to get across to audience members at all levels, about the life, election, and legacy of Maynard Jackson?

The election of Maynard Jackson showed how we could all work together to accomplish something monumental, no matter how different we think we are from each other. In the play, when tensions arise among several of the Citizens and the Witness about representation, they listen, carefully hear each other to appreciate all the voices, and try to resolve it together. You know, we make it so hard to welcome each other and to hear each other’s story, and it should just happen. It can be as simple as “Thank you for telling me that. I didn’t know that aspect of your life and experience.” I hope the play does that, invites everybody in, because we’re all a part of this story. That’s what makes it interesting. Our stories are all a hodgepodge of our realities, and that’s what we have to work on and figure out. We’re thrilled to work that out under the watchful eye of Abraham Lincoln.

You have such an optimism through these tumultuous times. In your writings, you’re upbeat and ready to keep fighting and keep flying. How do you keep that optimism flowing?

Because what’s the alternative? The alternative is to throw up your hands and give up, concede to the hate and craziness that’s out there? No, I’m not prepared to do that. I have great hope for and faith in the American people, that we can come together in all our crazy ways. People keep coming to this country with the optimism of finding something better. And we should keep working to make it work, not just for those coming in but for the people who are right here. It’s such a great idea, America.

I’m optimistic because I’m always hoping that people will come together and care about each other and do the right thing. Power used in the service for others, the community, your country, that’s real power. Working together we can harness that power — we want everybody to have safe housing, good schools, child care, medical attention. Until we have all that, I’ll keep writing plays, my poetry, do all I can do, because I think we can provide and care for each other. I know it. So no, I’m not prepared to give up on the potential and possibility of America, so I’ll keep pressing on.

How wonderful! We’re excited to see the results of Something Moving: A Mediation on Maynard, and we’re all the better for the experience. Thanks so much for taking the time to share your reflections with us.

You’re quite welcome. It’s a pleasure to be here and to share with all of you.

Something Moving: A Meditation on Maynard plays September 22 to October 15, 2023, (Tuesdays to Saturdays at 7:30 p.m.; Saturdays and Sundays at 2 p.m.), at Ford’s Theatre, 514 10th Street NW, Washington, DC. Tickets are on sale online and range from $18 to $48. Discounts are available for groups, senior citizens, military personnel, and those between the ages of 21 and 40.

The production is recommended for ages 10 and older.

Audio-described performances of Something Moving: A Meditation on Maynard are Wednesday, October 11 at 7:30 p.m. and Saturday, October 14 at 2 p.m. An ASL sign-interpreted performance is scheduled for Thursday, October 12 at 7:30 p.m. Accessible seating is available in the rear orchestra.

Beginning Wednesday, September 27, 2023, all performances of Something Moving: A Meditation on Maynard will be captioned via the GalaPro App. GalaPro is available from the App Store or Google Play and allows patrons to access captioning on demand through their phone or tablet device. Patrons set their phones to airplane mode and connect to the local GalaPro WiFi network before the performance begins. More information at www.fords.org/visit/

Two related events for this production are the Capitol Strides: From Civil War to Maynard Jackson walking tour on September 16 at 1 p.m. and Generation Abe Night on October 5 at 7:30 p.m.

SEE ALSO:

Ford’s Theatre announces cast and creatives for ‘Something Moving: A Meditation on Maynard’ (news story, August 3, 2023)

A look back at Ford’s ‘First Look’ festival of new plays (report by Debbie Minter Jackson, February 8, 2023)