BOOK REVIEW

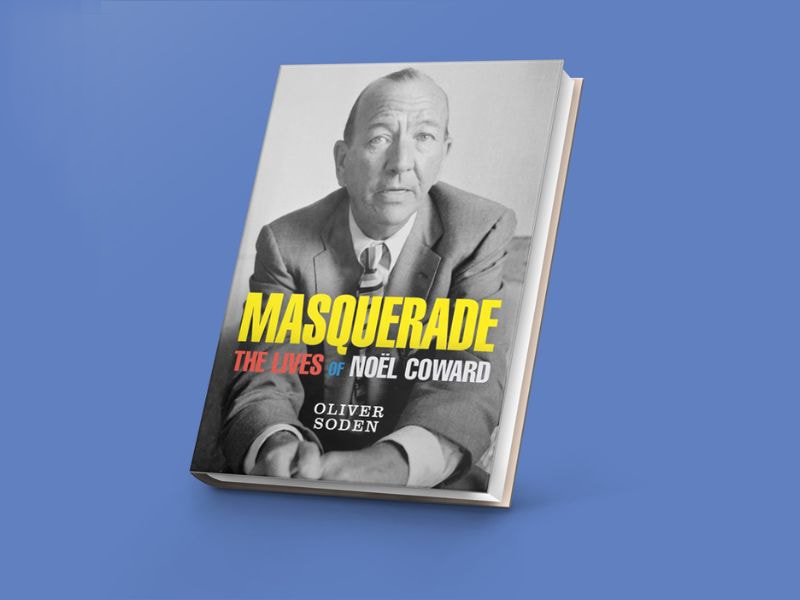

Masquerade: The Lives of Noël Coward by Oliver Soden

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2023

This biography of Noël Coward, the first in 30 years, tells the full story of one of the 20th century’s most iconic playwrights. Many of Coward’s comedies, such as Private Lives and Blithe Spirit, are still performed now, and he generally comes to mind when people think of British wit and sophistication. In addition to exploring parts of Coward’s life not discussed in earlier biographies, such as his love life and work during World War II, Oliver Soden’s Masquerade argues that Coward’s plays are more profound than they appear at first glance.

Coward, born in 1899, formed a close bond with his mother, generally taking up all her attention. He grew up on the stage as a child actor, appearing as one of the Lost Boys in productions of Peter Pan, and in some years was the primary breadwinner in his family. He continued to act throughout his life, appearing in many of his own plays and even starring as the criminal mastermind in the film The Italian Job.

The Vortex, his first successful play, shocked post–World War I audiences with its depiction of drug addiction, a married woman taking a much younger (male) lover, the son’s fiancée and the mother’s lover falling in love, and a near incestuous relationship between a mother and son. Soden also suggests many audiences saw codes for homosexuality in the son, though he admits the play has so much concealed that anything could be read into it.

Coward’s plays of the 1920s captured the values of the Jazz Age, with their candid look at sexuality, women’s freedom, and fast living and their witty repartee. Hay Fever, with its quick, rhythmic dialogue, feels reminiscent of T.S. Eliot’s poetry and Gershwin’s music. Design for Living even speaks of bisexuality and polyamory, with its two male characters in love with each other, as well as with the two female characters. Soden argues that these plays create a world where people can love whom they wish, regardless of gender, age, or marital status.

And the plays could also be seen as critiquing these values. The characters often seem frantic, never staying in one place for too long, changing lovers and places frequently. They never feel particularly happy. And they frequently hail from the upper classes, which means their social status and wealth protect them from the consequences of their behavior and the scorn of public opinion. As with most great literature, Coward leaves it open to the viewer how to read the society he depicts.

Some plays carry this undercurrent of critique even further. Calvacade, a musical history of England, feels celebratory of the country and its traditions; many people saw it as nationalistic at a time when, as in Germany, this felt dangerous. Yet, for instance, a woman makes a New Year’s toast just after her two sons have died in the Titanic sinking and World War. His late short play A Song of Twilight talks most explicitly about homosexuality, featuring a long-closeted writer being blackmailed in his old age with love letters. Besides being somewhat autobiographical, it criticizes a society that made homosexuality illegal and immoral, requiring gay people to be “discreet” and cautious, or risk blackmail, imprisonment, and disgrace. Soden argues that as a result, Coward’s plays show the need to be “authentic only in pretense” and “impossible to catch in the act of profundity.”

Coward’s love life was complex. He had many quick affairs throughout his life, but only a few long-term relationships. He seemed to have trouble turning romantic love into domestic quietness and disliked losing control in love. His first major partner, Jack Wilson, soon became a friend and business associate. Wilson first called Coward “The Master,” although he meant it sarcastically. Graham Payn, a former child actor, became Coward’s live-in lover from after World War II to Coward’s death. Cole Lesley was Coward’s valet and assistant, and he, Payn, and Coward got along so well that Payn called theirs a “threefold relationship.”

Before World War II, Coward served as a sort of unofficial agent, gauging the feelings of countries toward Britain. Before America entered it, he even met with President Roosevelt privately several times. Injuries kept him from serving in World War I, and he was eager to help this time, although some in Parliament wondered if he was the best “ambassador” for Britain. Later, he traveled around the world giving shows to British troops, often in terrible conditions and with a grueling schedule.

After the war, his plays flopped tremendously; of the 20 works he wrote then, only two have been revived. Society began cracking down on homosexuality, with the American government firing all suspected homosexuals. In 1963, a theater revived Private Lives, setting the costumes and references in the current day, to great success. Still, Coward claimed to hate the youth culture and contemporary playwrights like Beckett and Ionesco, although he later admired subversive plays like Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf and Entertaining Mr. Sloane. Toward the end of his life, he became a character himself, giving interviews with his cigarette holder, witty lines, and put-downs of current society. One interviewer wondered if he had spoken with Coward or “someone acting Noel Coward.”

Soden sets each section in the style of a different genre that Coward wrote in, so that headings are in screenplay, stage play, and short story formats. Generally, this feels clever and easy to follow, although an epilogue, written as a play, feels a bit confusing and unnecessary in the beginning. And there is at least one error: the famous 19th-century female poet was Felicia Hemans, not Hermans. Still, the book captures the life, work, and times of a remarkable playwright, arguing that his plays are concerned with the “search for freedom and truth,” but also show “the pain and sacrifice” that come with such a search. Perhaps this is why they still stand today.

Masquerade: The Lives of Noël Coward by Oliver Soden

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2023

634 pages; paperback, $38.29

ISBN-13: 9781474612807

A fine review of what seems a long, intricate, multi-dimensional book. Mr. Green deftly suggests that Soden explores, and in some cases freshly discovers, layers in Coward’s life that need to be pulled apart and re-examined. A life we thought we knew but really only had a glancing appreciation of.

I confess I was struck by this: “. . . he even met with President Roosevelt privately several times”. I couldn’t have imagined such encounters. One wonders what common ground the patrician president and the droll playwright discovered in conversation; I’d guess that Coward had insights into British pre-war thinking that Roosevelt found useful. Would love to hear more. Mr. Green makes this seem a book to get. I definitely will.