BOOK REVIEW

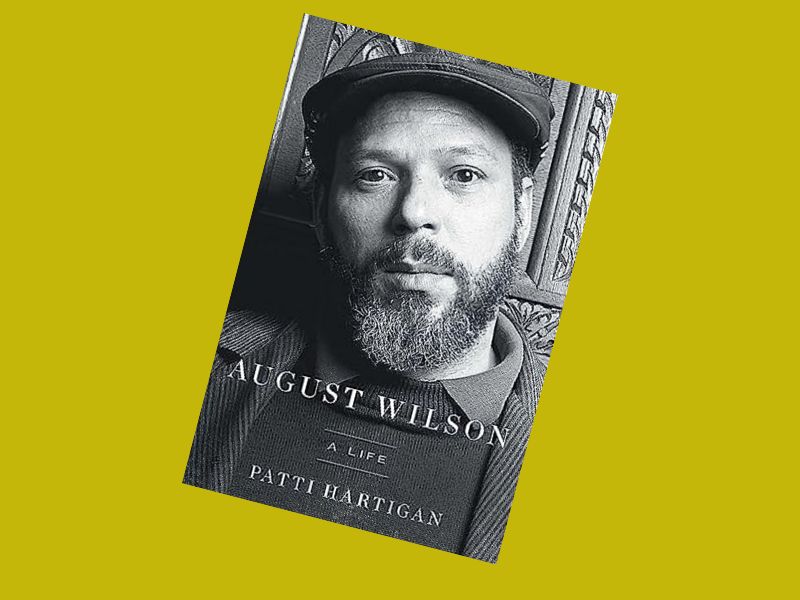

August Wilson: A Life by Patti Hartigan

Simon & Schuster, 2023

This first full-length biography of August Wilson tells the engaging story of one of the most successful American Black playwrights of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Patti Hartigan, a white journalist and critic who met Wilson early in both their careers, traces the course of Wilson’s life and works, from his childhood in Pittsburgh as the illegitimate son of a white merchant, through to his documenting each decade of 20th-century Black life in his Century Cycle plays.

Wilson faced challenges early on, living with his mother in a poor section of Pittsburgh, with an alcoholic, absentee father who had his own separate family. Wilson was a bright student who devoured books from the libraries, and his mother was determined for him to succeed and escape the life they knew. Unfortunately, Wilson had a short temper and attacked any perceived racism or slights, resulting in his expulsion from several schools. Determined to be a writer, he dropped out of high school and took a series of menial jobs, spending most of his days in diners drinking coffee and writing on pads.

With ambitions toward poetry, he adopted a literary persona, dressing in fancy clothes and reciting poems filled with literary allusions. He later encountered poet and playwright Amiri Baraka, which helped inspire him to write more about the Black experience he was familiar with, and to capture the language of “the street.” He could still be wildly ambitious. The title character of one of his first plays, Black Bart and the Sacred Hills, was a real-life outlaw who “left poems at the scene of his crimes”; Wilson turned him into a Black man “surrounded by electric angels” who turned water into gold. Another play, Jitney, about a low-cost bus service, proved more popular and was revived decades later to great acclaim.

Moving to St. Paul, Minnesota, and becoming involved in the theater scene there, Wilson was later accepted, after many tries, to the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center in Connecticut to develop his play Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. A lengthy, rambling story about blues musicians meeting for a recording session in the 1920s, it deeply impressed a critic who wrote about it while attending final-night performances of playwrights’ plays. This early praise helped launch Ma Rainey on the circuit of regional theaters, where it would be further refined during each stop. This would be Wilson’s method for working on plays.

The network of regional theaters seems to be one of the keys to Wilson’s success, allowing him to slowly see how changes in his work appeared onstage, without the pressure of having to get it ready for a Broadway production. As a result, for instance, while the encounters with the ghost in The Piano Lesson at first felt like hokey, old-fashioned stage magic, through several productions, the director and tech crew were able to figure out how to make it work.

Wilson also benefited from critics’ willingness to see the promise within the plays while understanding that each production was a “work in progress.” Hartigan mentions that this is a privilege rarely afforded other playwrights, which is both a testament to Wilson’s talent as a writer and evidence of the power critics can wield to help shape a career.

Despite this help, there were still challenges. During the run of Fences, James Earl Jones, playing the lead Troy, tried to force Wilson to rewrite the play, to show a reconciliation between Troy and his son, even conspiring with a producer to have the changes made. There frequently was conflict between Wilson and Lloyd Richards, his longtime director, who argued that Wilson’s success was because of their collaboration. Eventually, they parted ways, leading to awkward moments when they ran into each other at functions.

As Wilson’s fame grew, he became more outspoken. When Eddie Murphy optioned Fences for film, Wilson insisted that a Black director direct it; Denzel Washington eventually directed it in 2016. At a conference, he argued that “race-blind” casting was not useful or helpful. While Hartigan says he quickly wished he had not emphasized this point, it soon became a major controversy, with arguments back and forth in the theater community and the media. Conservative critic Robert Brustein weighed in, leading to a debate between him and Wilson, moderated by Anna Deavere Smith. Hartigan explains that Smith had wanted a meaningful discussion between the two, but due to hype and miscommunication, it became a tired rehashing of old views.

Some in the theater community further criticized Wilson. Because his work was generally more “traditional,” having it produced on national stages generally meant that more experimental plays were not performed. Some suggested that theaters included a Wilson play in their season simply to satisfy the need for “diversity,” with no intention of including other Black-written plays. Others wondered if Wilson, technically of mixed race, should be writing about the Black experience in the first place.

Wilson always considered himself Black, writing in the Black tradition. His temper sometimes got the best of him, sometimes taking out perceived slights on servers, bellhops, and front-desk people. Usually, though, he was quietly generous, tipping well in coffee shops and befriending a mentally ill man whose rantings annoyed other customers, even attending the man’s memorial service.

Hartigan carefully examines Wilson’s work. Fences, one of his most popular plays, is his most “traditional.” King Hedley II, set in the 1980s, is one of his least successful; Wilson did not understand or like the values and culture of the ’80s. His last play, Radio Golf, set in the ’90s and finishing the Century Cycle, is unwieldly and difficult. Wilson struggled with it while dying from liver cancer, desperate to finish it. In all his plays, Hartigan argues, Wilson combined the language of working-class Black people with poetic rhythms, turning their struggles into beautiful, if harrowing, drama.

Though Hartigan has a tendency to repeat phrases, the biography shows Wilson’s humanity and talent as a playwright. It is well worth reading.

August Wilson: A Life by Patti Hartigan

Simon & Schuster, 2023.

544 pages, $32.50

ISBN13: 9781501180668