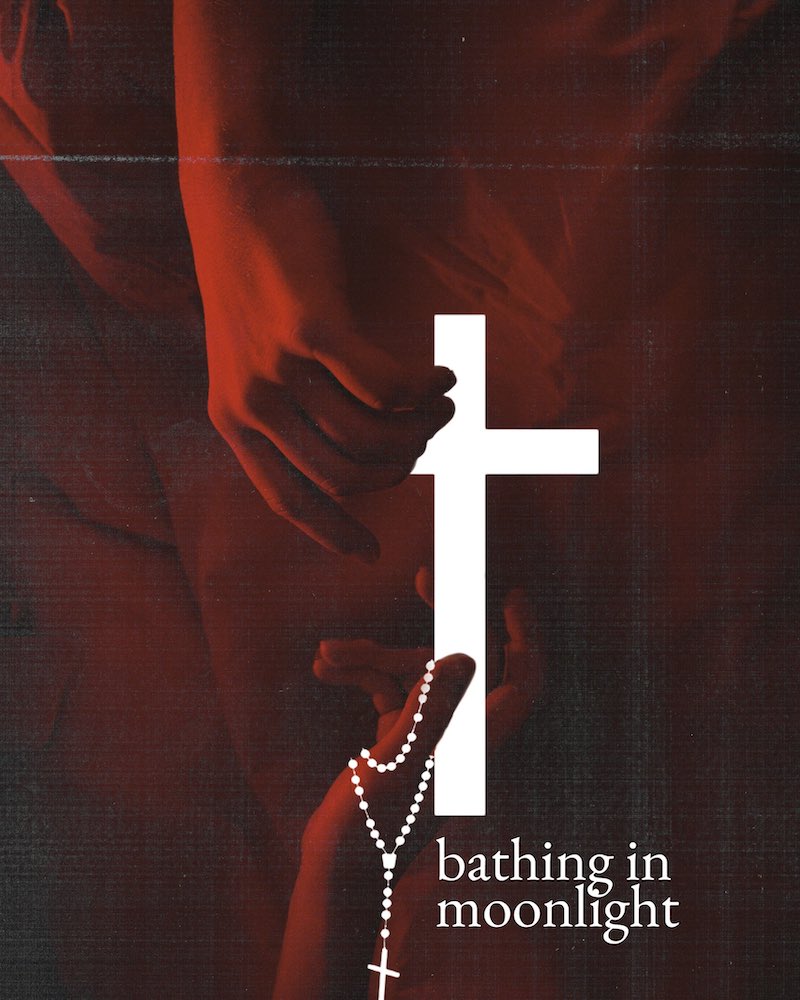

One thing playwrights and preachers have in common is that both like to tell stories, often to illustrate a larger point. Bathing in Moonlight (Baño de luna), a play about forbidden love by Pulitzer Prize winner Nilo Cruz (Anna in the Tropics, 2003), literally opens with a sermon illustration. Father Monroe, a Roman Catholic priest, is telling his congregation a story about inclusion and about removing the barriers, both societal and institutional, that separate one individual from another. The story is apt, and not only for Father Monroe’s congregation. The priest himself harbors a secret — and in the church’s eyes, forbidden — love for parishioner Marcela, a gifted pianist. Ultimately, he will be forced to choose between the institution he serves so devotedly and the woman whose life he longs to share.

I recently spoke with Cruz about love, inclusion, and Bathing in Moonlight, which opens under Cruz’s direction at DC’s GALA Hispanic Theatre on September 7. The play premiered at the McCarter Theatre Center in New Jersey in 2016 and was directed by Cruz (in a Spanish-language production) at Arca Images in Miami in 2017. The GALA production is in Spanish with English surtitles. The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Deryl Davis: You open Bathing in Moonlight with a monologue that is, in the context of the play, a sermon delivered by the character of Father Monroe. That’s an unusual way to begin.

Nilo Cruz: Monroe’s first speech, about removing the boundaries and breaking down the fences created in life, is very intriguing in terms of working with that initial sermon that he gives and then sort of that sermon serving as a guide to the rest of the play. I actually didn’t discover that sermon until much later. I don’t begin writing in a linear way, like “it would be interesting if the play opens with Father Monroe giving a sermon.” I don’t come to a play with a fixed idea. I discover a play as I write it, through characters more than plot. So, [Father Monroe] comes up with that sermon. These are things orbiting him, revealing his state of disquiet at the moment, how the personal affects his speech and his sermons. So that sermon is very personal to him, but also about things that we all should practice. About erasing the boundaries that are around us through practicing generosity, practicing compassion.

Are you specifically critiquing the Catholic Church here, especially its views on sexuality and celibacy, in the relationship between Father Monroe and Marcela?

The play didn’t start with the church, but with a story I heard about. I was visiting Miami in 2009, if I’m not mistaken, and there was a particular case of a Father [Alberto] Cutié who was very popular in Miami. He had a TV show, and people called him “Father Oprah.” He was as popular as Oprah on Spanish TV. Apparently, he was having an affair with a woman, and they were at the beach, and someone took photos of them. The photos were published, and it became a national scandal. This priest was ousted from the church. So, I thought to myself, “This is such an intriguing story. Here we are in 2009, and we’re still debating the concept of celibacy, the boundaries placed around people and who they love, especially priests.” It just became very intriguing to me. The story stayed with me, and at one point I think my agent said, “You should definitely explore that world. It could be very interesting.” So the idea stayed with me and simmered for a while.

Are you trying to convey a message in this play?

I don’t have a message, but I think any human being should have choices. I totally understand the devotion to God and the church. I’m not a church person, but I am completely devoted to my art. In that way, I feel like a priest, a monk. I’ve spent an enormous amount of time on my work, on playwriting, directing. Complete devotion to the art of theater. So I totally understand that commitment. But I also feel there is a kind of isolation that comes with that. I believe those who want to practice celibacy should, and those who don’t shouldn’t. But they should be free to choose.

Here we have the Catholic Church telling some people that they can’t have marital relationships. I’m interested in seeing those lines erased. But this is not a thesis play about celibacy. This is a play about an impossible love, about a woman who has lost her piano [sold to pay for her brother’s schooling] and a priest who is disgraced by having this furtive relationship with her. But the play isn’t just about that. There’s Marcela’s family [Cuban-Americans struggling to keep their home], whom I draw a lot of attention to. And with Father Monroe, he loses his church, but he gains a home [with Marcela]. It may be kind of a dysfunctional home, but it’s also a loving home in many ways. For me, the play has more to do with sacrifice, with what you are willing to sacrifice in name of love. You will find it in other plays of mine. In Beauty of the Father [2004], there’s sacrifice, as well. It’s a continual theme in my work. Here, I’m exploring it one more time, with a Catholic priest and a young female pianist, with Marcela’s art and her brother’s education, and the sacrifices that new immigrants [in this case, Marcela’s family] have to endure when they come to a new country.

Did you draw on your own experience in creating the characters of Marcela’s family, who are Cuban emigrants to America, as your own family was? [Cruz emigrated to the United States with his family when he was ten years old.]

There are similar elements, including being Cuban immigrants coming to Miami. In the play, the story of the father [Taviano Senior] and the suit he wears and everything that happened is very personal to me. My father got caught leaving the country, too, and arrived [in the U.S.] much later and was imprisoned just like the character in the play. [In the play, we learn that an elegantly suited Taviano Senior had attempted to escape Cuba in a fishing boat, but was recognized, apprehended, and imprisoned.] The story of Marcela is the story of a friend of mine, a man, whose mother sold his piano. This is what one does as a writer. We collect stories and put them together, whether in a novel or a play. So, that story [of the loss of a beloved piano] is also a real story, but told in a different way. I took flight with it.

There seems to be an element of what might be called magical realism in Bathing in Moonlight, specifically in the scenes involving the mother Martina, who is suffering from dementia.

There’s always an element of the magical in my work. I call it realism that is magical. It really stems from reality. Martina is a wonderful character who suffers from dementia. She’s trying to explore the world without losing her memory, but also to be creative with the memory that she does have, to go to places that are extremely imaginative and magical. I’m trying to say something about love here, too. Martina still holds onto love for her [deceased] husband and hopes that her husband will come and take her to the other world. It’s been great to play with her, to free her imagination and free her up from the impediments of her body and her mind. So, when she goes into the world of imagination, she almost seems younger, more limber with her body. We’ve played with that [in the GALA production] in order to illustrate the mindscape of the character of Martina.

You are also directing this production of Bathing in Moonlight. Do you prefer to direct your own plays? How often do you get to do that?

I actually started in the theater as a director. I don’t usually direct first produtions of my plays, but I have directed many of them. Especially lately, I’m directing more of my own work than in the past. I was supposed to direct a play here [at GALA Hispanic Theatre] last year, but the time was not the best time for me, because I was also premiering an opera. [El último sueño de Frida y Diego – The Last Dream of Frida and Diego – at San Diego Opera, for which Cruz wrote the libretto.] I really like to get my hands on the plays and explore them with actors. There’s sort of an immediacy to the material that you don’t have as a playwright. As a playwright, you must allow a director to bring his or her own gaze to the play, to have their own take on the play. They are given a certain kind of direct connection to the material, although it’s still open to the interpretations of actors as well as designers. It’s just delightful to see your own work in a new light. For instance, the set here [at GALA Theatre] is completely different from the one in Miami [at Arca Images in 2017, also directed by Cruz]. But this time, I’m working with an actor and actress who were in the [original] McCarter production [Raúl Méndez as Father Monroe and Hannia Guillén as Marcela]. I asked if they would be in this production. Hannia lives in Paris, and Raúl lives in Mexico, so they’ve come a long way to be in the show.

Given its storylines and themes, do you think Bathing in Moonlight has a particular resonance for the time in which we’re living in America?

I think the whole concept of compassion, of being receptive to others, and the whole concept of generosity is very important. Erasing some of these lines we create. For instance, at the beginning [in Father Monroe’s sermon], there are questions about sanctified grounds [for burial] and about breaking those boundaries and including others. The play is very much about inclusion. Now that the country is so divided, the initial sermon by Father Monroe speaks to our time. The whole kindness of characters to embrace Father Monroe when he loses his place in the church is also quite beautiful. In some ways, this serves as an example to us nowadays to be more inclusive, compassionate, more giving overall, especially when our nation is so divided. It’s beautiful when we can do that, resonate on so many levels. Not just the specificity of the story that resonates on other levels, but also the ripple effect that art can have.

Bathing in Moonlight (Baño de luna) plays September 7 through October 1, 2023 (Thursdays to Saturdays at 8 pm, Sundays at 2 pm), at GALA Hispanic Theatre, 3333 14th Street NW, Washington, DC. Purchase tickets online. Regular tickets are $48 from Thursday through Sunday. Senior (65+), military, and group (10+) tickets are $35; and student (under 25) tickets are $25. Noche de GALA tickets are $55 each. For more information, visit galatheatre.org or call (202) 234-7174. Tickets are also available on Goldstar and TodayTix.

In Spanish with English surtitles.

COVID Safety: All performances are mask-optional. See GALA’s complete COVID-19 Safety Policy.