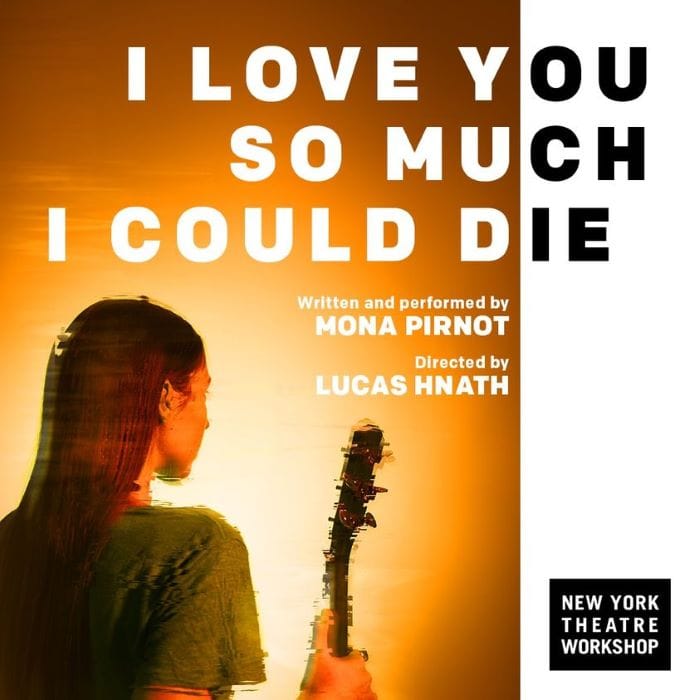

When several attempts with group therapy sessions, volunteering for a charitable organization, reading books, and a say-what-you-see out-loud exercise (picked up from actor Shia LaBeouf) to take her mind off her omnipresent grief didn’t succeed in alleviating the pain of a devastating family trauma that occurred in March 2020, at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, playwright and performer Mona Pirnot decided that the best release would be to write it down in stories and song. That’s what she did, and the result is I Love You So Much I Could Die, now playing a limited Off-Broadway world-premiere engagement at New York Theatre Workshop. Directed by her Tony-nominated husband Lucas Hnath, who was there with Pirnot through it all (both are also Usual Suspects and long-time members of NYTW), the extremely intimate autobiographical memory play, concert, and psychological study is presented in a uniquely contemporary way that underscores her unspeakable heartrending experience and draws in the audience with its slow reveal and universal humanity.

Pirnot enters the stage from the house, facing away from us, in a denim shirt and jeans – an everyday outfit that most of us wear (costume design by Enver Chakartash). She then sits, with her back to us, alone at a central folding table with a laptop computer, microphone, water bottle, and bedroom lamp, with floor speakers diagonally in front and behind, and an acoustic guitar in a stand to her right. The space that surrounds her is large and empty, defined only by the three exposed-brick walls of the theater (scenic design by Mimi Lien), emphasizing her intentional withdrawal and emotional isolation, and allowing us, also facing the back wall, to see things from her perspective.

We hear the descriptions of her failed efforts to deal with the process of grieving (as cited above), get glimpses into her background and her family, time spent between Florida and NYC, the development of her relationship with the unnamed Hnath (a shy “playwright with big eyes and big hair, who later became as famous as playwrights can get”), and, eventually, bits of information about the medical emergency that precipitated her overwhelming despondency, and another that raises the issue of euthanasia (no spoilers here, since it’s a revelatory process that keeps us engaged and wondering as it unfolds). And through it all, Pirnot never speaks a word; it’s all conveyed by the computer on which she wrote about the events, her thoughts, and feelings, via the virtual male voice of a digital text-to-speech program, activated when she presses a key, with the moving cursor visible on the laptop screen.

Though the computer-generated delivery is unemotively robotic (and at times humorous, with differing pronunciation of LaBeouf’s name, and in recounting Pirnot’s honest reactions to certain people, situations, and thwarted desire to commit an act of arson), the pacing changes from slow and clearly modulated to segments that are more rapid, suggestive of the increasing panic she felt and the words she might not be able to get out in her state of sorrow; we get the sense of what she’s going through without putting her through the added misery of having to vocalize it and likely breaking down in tears. Such exploration and employment of audio devices have become a signature feature in the work of Hnath, who previously used tape recordings in his plays A Simulacrum and Dana H., to excellent effect, as is the case here (sound by Mikhail Fiksel and Noel Nichols).

The potent narrative is interspersed with five original songs (with music direction by Will Butler), sung live by Pirnot in her own sweet and tender voice, accompanying herself on guitar and sometimes tapping her feet, while still seated and facing away from us. They’re filled with genuine emotion and heart, and more touches of humor, from wanting to be the old “Good Time Girl” she was (vocally imitating the sound of an electric guitar, which, we are told, it should be played on but she doesn’t have with her) to the deeply expressive title song and closing number, contemplating the inevitability of her own death and her wish to be treated “as I would do to you,” which left me reaching for a tissue to wipe my eyes. The performance is enhanced with Oona Curley’s evocative lighting, which slowly, steadily, and barely discernibly dims from the initial full brightness of the stage and house to increasing darkness, ultimately illuminated by only the computer screen and lamp, which, after her final song, Pirnot closes and turns off, leaving the theater in a total metaphorical blackout.

For theater to be compelling, there must be empathy on the part of the creator and performer, which then elicits it from the audience. I Love You So Much I Could Die is a brilliant example of profoundly felt relatable emotion and a must-see experience for everyone who appreciates the most current ways of expressing what is too painful to discuss but needs to be released. It left me deeply moved and hoping that it helped Pirnot to work through her grief, without ever forgetting or negating the importance of the love she has and the validity of her trauma, which are so beautifully and affectingly commemorated for posterity here.

Running Time: Approximately 65 minutes, without intermission.

I Love You So Much I Could Die plays through Saturday, March 9, 2024, at New York Theatre Workshop, 79 East 4th Street, NYC. For tickets (priced at $45-75, plus fees), go online.