By the time Doug Robinson finishes telling a story, he’ll likely make his listener smile from ear to ear. At least, that’s what happened to me when I recently interviewed the playwright over Zoom.

The multi-hyphenate theater creator is from Virginia and has had his plays staged in a variety of DC-area theaters, including Faction of Fools and Imagination Stage. His writing, which features both delirious whimsy and emotional intelligence, earned him a MacDowell Fellowship. He also recently earned an MFA in Playwriting from the Geffen School of Drama at Yale.

Many of Robinson’s plays engage with a mythological or folktale structure while still subverting audience expectations. I asked Robinson how he first developed his love of folktale, and he explained that he was introduced to them as a child. He was enthralled with a watercolor picture book retelling the Japanese legend of Urashima Tarō. In the story, the fisherman Urashima Tarō saves a turtle who is revealed to be the daughter of the emperor of the sea. Tarō is taken to an underwater palace but is allowed to go home with the condition that he never open a mysterious box. When Tarō returns, he finds that an immense amount of time has passed. He opens the box and ages rapidly.

It’s one thing to read the Japanese legend. But it’s an entirely different experience to hear Robinson tell it, with his animated, bright voice. He’s unafraid to retell an ancient tale in his own voice. When recounting the beginning of the story, he told me, “And the turtle’s like, ‘Bet, come back tomorrow. I’m going to have a little surprise for you.’” Robinson’s version was told quickly, with boisterous energy — but when dramatic story beats arrived, he was able to slow down and convey a sense of wonder. Afterwards, even though I’d gone through a narrative whirlwind, I still smiled. I was happy to have gone on such a surprising journey.

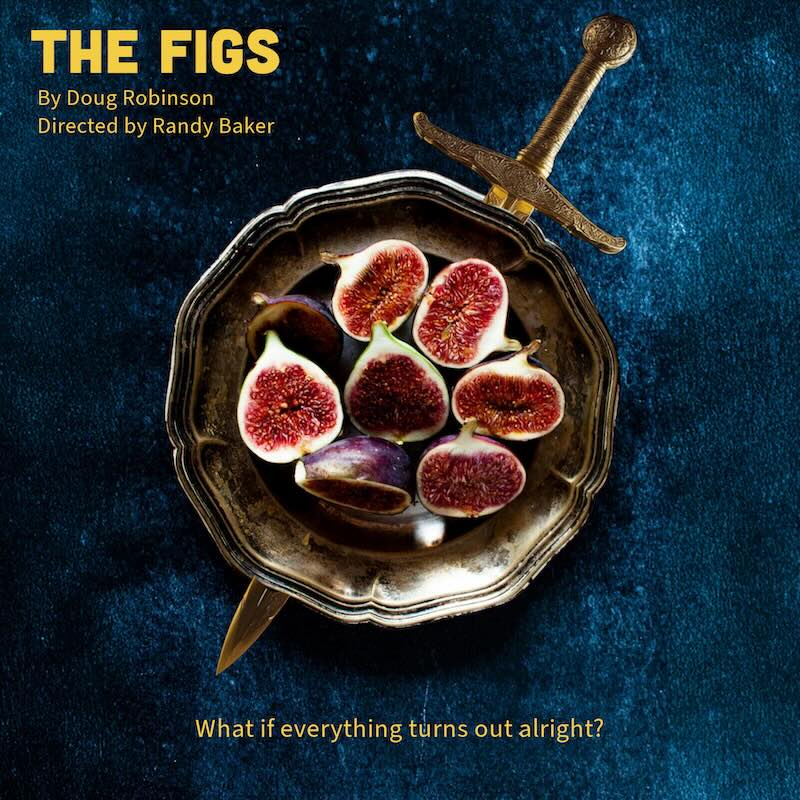

Audiences can feel Robinson’s giddy but methodical storytelling in his play The Figs, running at DC’s Rorschach Theatre through March 16. The play is a strange, contemporary folktale. It starts with a Storyteller sharing a fable (also embodied onstage) about a king who’s obsessed with figs — until a lack of them drives him mad. Robinson’s play then spirals out in multiple directions. There’s a competitive family of three siblings (Jin, Jod, and June), all determined to share their figs with the King. There’s the King’s daughter Sadie, who runs away to her secret love, the innkeeper Lorna. There’s also plenty of smaller storytelling moments, from songs and mythology to anecdotes and asides.

Audiences watching The Figs will pick up on Robinson’s admiration for (and interrogation of) the act of storytelling. The playwright told me his love of folktales stemmed back to that watercolor picture book and how it blended the mundane with the spectacular.

“There was magic, but also everyday people,” Robinson said. “This was just some fisherman who then found this magical moment. I think so much of what I hope to see in theater is the magic in the ordinary. Where does that exist? How can we punch that up?”

Robinson said that while putting together The Figs, he intentionally wrote a large-scale story. He referenced the tale of Jack and the Beanstalk, which starts out as the story of one boy but twists into unexpected directions, with the Giant and Jack’s mother becoming main characters in different parts of the story. Robinson sought to honor this narrative approach.

“A good folktale or fairytale, if we move away from the Disneyfied version of it all, often has many winding threads of a different color that coalesce in this thing of many events,” he said. “But it’s really more like this tapestry of people who keep intersecting, and then it ends.”

Robinson’s tapestry of people features many characters who pop up for a few scenes, make a huge impression, and then quickly exit the play. These include a “Messenger” who introduces dire news like a customer care agent. A “Nurse” arrives in a pivotal scene with deep insight into the sacrifices made for love. Most memorable is probably a little white fish, who in just two scenes develops an adversarial but also affectionate relationship with June.

Robinson said that every time he presents The Figs, whether in a reading or a production, audience members will always share that their favorite character in the show is the fish. Although The Figs is full of witty humor, it always comes from characters who are trying very hard to achieve their goals — a character trait Robinson very much appreciates.

“I think the good thing with comedy is it doesn’t need to punch down,” he said. “It can also be a reminder of our own connected foolishness.”

For Robinson, writing many minor characters like the Messenger, the Nurse, and the Fish allows him to tell his audience that so much is possible in his plays.

“I think why it works, to have all these characters, is I try to build a world first and foremost,” he said. “Once the audience has accepted the rules of that world, which are that people of all sorts can appear and engage, they’re actually excited and hungry for the next discovery.”

Even with a hunger for discovery, there’s a risk for any storyteller telling a winding tale: they’ll test the patience of an audience. The Rorschach production of The Figs lasts two-and-a-half hours plus an intermission. Robinson acknowledges the risk of losing an audience — he doesn’t want the audience to go, “Oh God, another fucking thing?” when a new character arrives late in the story. But he also shares that the original draft of The Figs was “40 pages longer.” He did significant editing to balance all the storylines and characters while not compromising a folktale structure. The question he asked himself during edits was, “What fills the world but does not oversaturate the world?”

“The world is so big, yet we can only get a little snapshot of it,” he said. “It is a good story’s job to remind audiences of how vast the world is and the many possibilities that exist. To not show a singular path, not show one right way of being, but to remind us there is no single thing and there can never be a single thing.”

Because of The Figs’ vast world, many audiences might draw parallels to real life. Although most of the play takes place in an anachronistic fantasy land, I find many resonances between characters trying to survive a tumultuous political era and my colleagues and I doing the same in 2025. This DC production about a power-hungry king is being staged at the same time that the President of the United States is sharing royalty-inspired artwork on social media that reads “LONG LIVE THE KING!” There are juicy, uncomfortable comparisons to be made, even if The Figs doesn’t function as a one-to-one allegory of the present day.

I asked Robinson how he believes “evil” functions throughout folktale storytelling, and thus within The Figs. Robinson said that although he doesn’t excuse violence that characters commit, he’s also not interested in completely antagonizing his characters. Mostly, he doesn’t find the idea of “evil” to be compelling for writers or audiences.

“I don’t think that evil makes good dramatic action, whether it’s in a folktale story or a contemporary lens,” Robinson stated. “I think people with unchecked power is an interesting bit of dramatic action. I think people who choose to be kind in the face of cruelty is interesting in dramatic action.”

LGBTQ audiences and audiences of color might find personal resonance with The Figs as well. As a member of both communities, I’m fascinated by metatheatrical moments in Robinson’s script, when characters acknowledge the societal roles they’re asked to perform. Sadie tells the King early on, “Don’t play the caring father. The costume is ill-fitting.” After a tragedy, June remembers being sidelined when playing with their siblings: “I had to take the part they gave me or I couldn’t play. I didn’t play very much.”

Even though Robinson isn’t explicitly writing about contemporary systemic oppression, his words feel true to people experiencing them. I’m reminded, weirdly, of what critic Wesley Morris wrote about the horror film Get Out: “[Filmmaker Jordan Peele] made a nightmare about white evil that doubles as a fairy tale about black unity, black love, black rescue.” Now, The Figs is much more playful than a horror film. But I see the show as operating on a similar level as Get Out. Both artworks confront painful injustices, but their use of genre tropes create an accessible entry point for marginalized audiences, who together can root for our collective rescue.

The Figs articulates that mission toward the end of the show. June, who emerges as a central figure, enters a liminal space that the Storyteller calls “the margins.” “Everything that could be and even the things that couldn’t be exist in the margins,” the Storyteller remarks.

Robinson told me this scene was one of the last he wrote for the play. He was collaborating with director Helen R. Murray on the show’s 2024 world premiere production at American Stage, and they both wanted to express how expansive the world could be for the characters.

“This is not a story about June who reunited with [their] ‘nuclear family,’” Robinson told me. “This is not that story. In fact, this is a story about someone who finds a family on the road, who realizes that they’ve had companionship of a different kind their whole life, and a love that is going to transcend that kind of Americana look.”

The Rorschach version of The Figs, only the show’s second professional production, offers a unique journey for the audience. Director Randy Baker has created an immersive experience where audience members physically travel through Rorschach’s performance space, previously a two-story clothing store. Although audiences eventually settle into seats, the staging mimics the twisty narrative of the play itself.

With this production, Roboinson said he’s finding a balance between being available to the creative team for feedback while also giving Baker and producer Jenny McConnell Frederick enough distance to reimagine the show on their own. Robinson said he’s happy to participate in theater any way he can.

“If someone said to me I couldn’t be a playwright — cool, whatever, fine,” he stated. “But if someone told me I couldn’t make theater, I’d be devastated. Being in every aspect, engaging whether it’s tech or auditions, I’m overwhelmed just to be there every time. So I’ll be a part of any production as long as people will have me.”

This production comes at an interesting time in Robinson’s career as well. Looking back on his time at Yale, he’s said he’s thankful that the program allowed him to develop his own unique writing process, even if he learned the most from his fellow playwriting peers. Robinson also admits that being a Yale graduate opens certain doors for him — but he’s “forever grateful” to the theater companies like Rorschach, which read his play submissions earlier in his career.

Robinson is now working on a new play, Cactus Queen. It’s a story in which a mother attempts to resurrect her dead son, who is played onstage by a puppet. Although it might seem like a darker departure from both The Figs and some of his work for young audiences, Robinson believes all his work is tied together through imagination.

“I want [audiences] to say that my plays made them see the scale that theater can be,” he said. “That doesn’t mean scale like budget and all the big sets. But look at that little puppet. Look at that little puppet catching a butterfly. Look at that grieving mother hold that puppet like it’s her own child. I believe that that is her child. Oh my God, I’m believing in something. I’m not suspending my disbelief, I’m choosing to actively believe.”

Belief — in the arts, in institutions, in the country — is being tested right now for artists and audiences in the DC area, as the government asserts an increasingly large role in arts organizations locally and nationally. The Figs didn’t immediately strike me as a show about resistance or revolution. However, the longer I’ve thought about it, the longer I’ve appreciated how the play’s characters don’t seek out joy or a happy ending. They instead seek out stronger integrity.

“If there’s one value I hold most dear in this moment of my creative process, it is a deep love for earnest characters, earnest storytelling,” Robinson told me. “Cynicism and irony have their place. I love the absurdist. I love my fucking angry, burn-it-down play, I do! I just don’t have it in my spirit to write that right now. What is in my spirit is to write people who — in the midst of storms, and ungodly things, and unholy things, and cruel things — choose to believe in something, choose to really put themselves in the action that they are doing. Not with a wry smile, not with a sardonic attitude.”

I wondered how, in the midst of so much unrest, Robinson was able to foster such an imaginative approach to theater. Over the past few weeks, I’ve felt jaded and emotionally exhausted, considering leaving the arts industry altogether. I admire, and perhaps envy, Robinson’s ability to feel so connected to the younger version of himself who asked his mother to read a watercolor picture book over and over again. In our conversation, Robinson emphasized that he isn’t staging the wonder of childhood. Everyone else might be performing a kind of stolid maturity.

“I think adulthood is kind of a costume more than it is a thing that actually happens,” Robinson said. “I pay taxes. I have responsibilities. Let’s not pretend that life doesn’t get more complicated. But this idea that imagination — or silliness or playfulness or earnestness and believing in something — is a naive concept seems antithetical to what is needed for the world to move forward. Actually, it is through imagination that we can dream and think beyond our current circumstances.”

“I take many things in this world seriously,” Robinson continued. “I am a student of history and philosophy, and I am not someone who believes that everything is happy-go-lucky. But I also think that imagination is the only way forward.”

The Figs plays through March 16, 2025, presented by Rorschach Theatre performing at 1020 Connecticut Avenue, Washington, DC. Purchase tickets ($50 adult, $35 student and seniors) online.

Running Time: Two and a half hours with a 15-minute intermission.

The playbill for The Figs can be downloaded here.

SEE ALSO:

Rorschach Theatre’s ‘The Figs’ tells a bizarre fable about an obsessed king (review by Haley Huchler, February 19, 2025)