Most of the time, life changes incrementally. Bodies sag and falter slowly. Political action takes one step forward and two steps back. Light fades on a summer evening before you realize darkness has settled in, and days fade before you realize years have settled in. But there are also rare times when life transforms dramatically. The world opens up, and can’t be closed again.

Watching Moonlight as a teenager was one of those rare times for me. The film, written and directed by Barry Jenkins and adapted from the play In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue by Tarell Alvin McCraney, is a coming-of-age triptych. The film’s first act follows the young Black boy Chiron as his community struggles to raise him; the second act sees a teenage Chiron discovering his queerness and attraction to his friend Kevin; the third act has an adult Chiron undoing the hardened masculinity he’s used as protection. When I was 17, I stumbled across Moonlight’s hypnotic trailer ahead of its release in the fall of 2016, and convinced my mother to watch the film with me on a rainy Thursday. Despite it being a school night, she relented.

Up until Moonlight, the world of bodies seemed strange to me. I’d watch guys on the sports field or stage, and overhear stories about them in dimly lit basements. I’d imagine their exhausting movement of spit and limbs, but never taste them myself. Instead, I lived in my head. I’d read novels with nerdy, metaphor-inclined teens like Hazel Grace Lancaster, Dante Quintana, and Oscar Wao. They seemed bursting with ideas. I’d pore over Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, especially when she considered the different definitions of the word “queer.” For Bechdel, queerness was a site of theoretical exploration, and I was eager to jump into the discourse. I didn’t want to just come out. I wanted to write about queerness like Bechdel did, with methodical evidence and annotations. Instead of just being myself, I needed to present myself.

Moonlight was the queer rupture I needed at 17. Instead of dissociating in the cinema, I arrived into my body for the first time. The film is composed of poetic, sensual images. Water caressing the head of a boy. A hand grasping at sand. A mother fumbling with a lighter. An ocean breeze dancing across a white shirt. A hand caressing the head of a man. To this day, Moonlight is my favorite film. But as a teenager, the film’s imagery proved that my queerness didn’t need to be researched or justified to be beautiful.

Moonlight was my gateway into physicality. Watching the film quieted the overwrought, anxious, analytical madness that defined my life — replacing it with a calm, warm, embodied presence. I realized I didn’t want to find love with just any guy. I wanted to find love like Chiron’s. Moonlight consecrated my abstract queerness into flesh and blood.

It’s a surreal twist that while I watched Tarell Alvin McCraney’s latest play, We Are Gathered (making its world premiere through June 15 at Washington, DC’s Arena Stage), I felt trapped in my head again. The play’s protagonist is actually similar to the characters I idolized as a teenager: he’s nerdy, metaphor-inclined, and bursting with ideas.

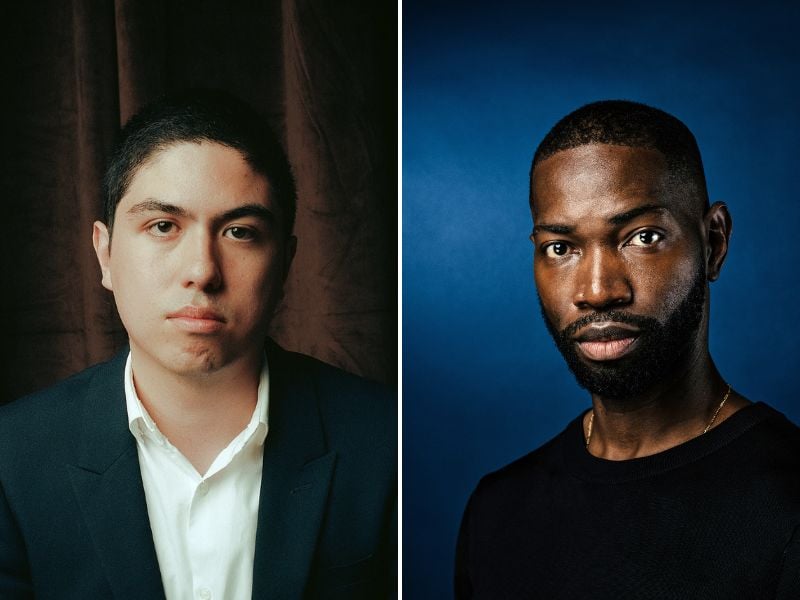

His name is Wallace Tre — but his friends call him both “Tre” and “Dubs.” As played by Kyle Beltran, Tre opens the show directly addressing the audience, explaining that he’s anxiously considering a marriage to his gay partner Free (Nic Ashe). Tre expresses himself through neurotic, stream-of-consciousness monologues. But Free is a boisterous musician, the life of the party. Free just is himself, while Tre presents himself.

The party at hand is Tre’s 40th birthday, a celebration that includes his playful friends Chauncey (Kevin Mambo) and Xi (Jade Jones), but also surprise guests: his astronaut sister Punkin (Nikkole Salter) and their somewhat estranged father, Sr. (also played by Mambo). Sr. starts asking about his son’s sexuality, blaming Tre’s queerness on his own absence during Tre’s childhood. In response, Tre furiously reveals his self-loathing and fear of commitment with Free:

TRE: And now that life is in front of me, I don’t know! And he wants a life! And I don’t even know if I can give him that. Or if I will be able to get over my … self to. And is that enough to do it, just because they might take it away from us? Should we do it ’cause we can because when we can’t? All these questions in my fucking head and you wanna add more?!

It’s only after this exchange that the dramatic stakes of We Are Gathered come into focus. Can Tre accept that he’s deserving of love? Can queer millennials like Tre reconcile their painful childhoods with the tenuous freedoms of adulthood? Answering these questions takes We Are Gathered on discursive paths. Tre wanders obsessively through the park where he first encountered Free while cruising. McCraney wanders through many dramatic forms over the two-act play.

Audiences yearning for the poetry of Moonlight will find it in Tre’s beautiful descriptions of sex (he pays attention to details like “bit lower lips, spit curled tongues, teeth gnashing as fingers find forever”). However, for most of its runtime, We Are Gathered stages the tension between physicality and intellect. Tre feels safe when holding Free, but he’s prone to overthinking how marriage is “a cultural norm made worse by late-stage capitalism.” It’s as if before Tre can love, he must formulate the proper theory for his queerness. Moonlight may have welcomed me into physicality, but We Are Gathered now challenges me with the analytical madness I felt as a teenager, and feel today as a writer. The difficult union between body and mind: that’s the real marriage under question.

We Are Gathered is a significant departure in McCraney’s playwriting style. His Brother/Sister Plays took place in what he calls the “distant present” — an anachronistic space of Black Southern vernacular and dreamy Yoruban ritual. Scholar David Román argues that the distant present “forces us to consider when the contemporary moves from now to then.” Moonlight similarly plays with time, evoking a familiar yet strange world. “I never want to make something that feels so finite that we can only do it at that point, and that’s it,” McCraney stated in a 2017 interview about the film. “I want to make something that feels like we started in a specific place, but we can keep unpacking it for years to come.”

What a difference eight years make: We Are Gathered takes place in the finite here-and-now. Tre’s anxieties about gay marriage are only legible in a 2025 America that passed Obergefell v. Hodges but also overturned Roe v. Wade. His politics also take on a sharp tone when staged in the nation’s capital. McCraney doesn’t name names, but everyone at Arena Stage knows Tre’s talking about Trump when he tells his father, “You voted how you feel about me.”

In the more tangible world of 2025, McCraney luxuriates in contemporary media. Characters reference Pokémon, How to Get Away with Murder, and Sally Field. They ponder Caryl Churchill, quote Shakespeare, reference fairy tales, and close-read Bible passages. McCraney himself alternates between genres — from the marriage plot to the trauma plot, from call-and-response to realist drama, from broad comedy to prayer.

At their best, these dramaturgies create a fascinating friction when brushing up against each other. It’s a riot when Kyle Beltran asks the buttoned-up DC audience to define cruising, or when Free’s grandparents (Jade Jones and Craig Wallace) endearingly ask for details of their grandson’s sexual exploits. McCraney’s arguing that queerness doesn’t belong just in the nightclub or the bedroom — it belongs everywhere, even in the family function.

But at their worst, these dramaturgies compete with each other, rendering the staging and story tedious. The bare scenic design, mostly lamplights, hardly evokes the sweaty erotics of cruising. Even in this highly detailed world, we barely know anything about Punkin’s and Xi’s inner lives outside of their devotion to Tre. We Are Gathered also feels too reliant on monologue. Tre and Free elucidate on pleasure and danger, but the play rarely feels viscerally pleasurable or dangerous. We don’t even get to relive Tre and Free’s meet-cute; Xi just quickly narrates its story.

Of course, staging the past might be antithetical to McCraney’s project here. His pinballing dramaturgy seems like a challenge: can he write beyond an origin story? From Wig Out! to Choir Boy, McCraney’s writing has primarily centered on teens or twenty-somethings wrestling with identity. Even when his TV series David Makes Man focused on adult characters in its second season, it also employed a generous flashback structure. We Are Gathered is still obsessed with origins: Tre shares his first time encountering “faggots” in literature; Free discusses his first cruisings at a college gym. But the play never flashes back to youth for an extended period of time. This is a show resolutely about middle-aged men.

Maybe as McCraney gets older, his “distant past” will age with him (he’s 45 now, writing characters slightly younger than himself). As more millennial playwrights mature, and cash in “blank checks” to write whatever they want, their styles chaotically expand into the chaotic present. We Are Gathered reminds me of recent plays by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins: The Comeuppance and Purpose. All three of these shows center on middle-aged Black male artists, self-inserts for their authors. All three shows follow rituals (a high-school reunion, a family dinner, a wedding), with large ensembles debating social issues. All three shows are sprawling, overly verbose, intricately plotted, and messy. Honestly, same.

Watching these plays, I see brilliant minds set loose. Overtaken with ideas, my body slips away. I wander across the endless realm of my mind, creeping toward the future. McCraney and Jacobs-Jenkins acknowledge that they’ve finally come of age. Now what?

This past February, theaters across the country screened a one-night-only IMAX version of Moonlight. Rewatching the film for the first time in years, I was undone all over again by Moonlight’s aching images.

While a film will always stay the same, its viewers will inevitably change. When I watched Moonlight at 17, I had never touched another man, never expressed my sexuality on the page, never been heartbroken, never pleaded for forgiveness when I didn’t deserve it. The romantic scenes between the teenage Chiron and Kevin unfolded like a premonition: here is your near future, if you’re willing to claim it. I did. Yet watching Moonlight at 26, I realize I’m currently much closer to the Chiron and Kevin of the film’s third act. Like them, I’m an adult toughened by my younger self’s choices, secretly believing grace might be possible for me. I can’t let the past go.

Moonlight has become my distant present. It’s my queer origin story — the kind of origin that McCraney now encourages his mature characters to move beyond in We Are Gathered. “You found him,” Punkin tells her brother, asking him to let go of the shame of his first encounter with Free. “Your search for intelligent beings yielded a life you could form; a full life. You found it existed. Fuck how.”

Punkin may as well be talking to me, and my obsession with the first time I basked in Moonlight’s glow. I’ve been chasing that transformative feeling ever since, always thinking that I’ve failed. When I write about McCraney’s art, I feel the magic of his words slipping away through explanation. Maybe, like Tre, I’m overthinking things. As a teenager, I miraculously discovered that queer life was possible. How I received that message ultimately doesn’t matter. It came from the body and the mind; from poetry, prose, film, and theater; from academia and love. Fuck how.

Even though We Are Gathered and Moonlight tonally feel worlds apart, they’re bound together by McCraney’s collapse of linear time. In the program for We Are Gathered, Arena Stage Literary Manager Otis Ramsey-Zöe references José Esteban Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. He specifically cites Muñoz’s configuration of sexuality as an optimistic gesture toward the future: “Queerness is a longing that propels us onward, beyond romances of the negative and toiling in the present.”

What’s ironic is that academics have used McCraney’s art to critique Muñoz, especially his hope that the future will be better for Black and queer Americans. Scholar Aliyyah I. Abdur-Rahman uses Moonlight as a primary example of what she calls “the black ecstatic,” a representational mode that celebrates Blackness in an abstracted present, not an imagined utopia. “A post-civil rights expressive practice, the black ecstatic eschews the heroism of black pasts and the promise of liberated black futures,” she writes, “in order to register and revere the rapturous joy in the broken-down present.”

I’m overwhelmed with the beauty of Muñoz’s and Abdur-Rahman’s arguments, even if their theories are incommensurable. Which queer movement will I follow? Will I imagine a future beyond “toiling in the present,” or will I ecstatically revere the “broken-down present”?

By blurring adolescence with maturity, McCraney tries to move in both directions, to affirm both theories — to have his wedding cake and eat it, too. Especially in its third act, Moonlight celebrates the broken-down present by staging intimacy in real-time. But the film ends right as Chiron and Kevin have their long-delayed unification. We’re allowed to imagine their future without having to experience its likely excruciating path forward. If We Are Gathered is overstuffed, it’s because McCraney wants us to feel that excruciating path forward. Tre and Free arduously propel themselves into the future, through the mess of daily life, overanalysis, political threats, and yes, references to Sally Field.

Even more than championing marriage, We Are Gathered champions resilience. Queer life might not “get better,” but it will be. Many audiences will talk about the play’s ending, a satisfying conclusion where lives change dramatically. But in the preceding hours, McCraney celebrates incremental change, the accumulation of love that forms the foundation of a dramatic moment. You can’t achieve the rupture of Moonlight without the personal and artistic processing portrayed in We Are Gathered.

The present moment in We Are Gathered is not distant, but so close — and maybe for me, it’s upcoming. If I survive long enough to see 2039, I’ll be 40. I might taste the mature love seen in We Are Gathered instead of just witnessing it. The play will have become a period piece, a curious time capsule of our anxieties in the distant present of 2025. But I hope the accumulation of years has made the show more urgent.

Every piece of art can be an origin story for our lives, if we’re willing to claim it. I did with Moonlight, then. And I do with We Are Gathered, now. I do.

We Are Gathered plays through June 15, 2025, in the Fichandler Stage at Arena Stage at the Mead Center for American Theater, 1101 6th St SW, Washington, DC. Tickets are available online (starting at $59) or visit TodayTix. Tickets may also be purchased through the Sales Office by phone at 202-488-3300, Tuesday through Sunday, 12-8 p.m., or in person at 1101 Sixth Street SW, DC, Tuesday through Sunday, 2 hours prior to each performance. Groups of 10+ may purchase tickets by phone at 202-488-4380.

Arena Stage’s many savings programs include “pay your age” tickets for those aged 35 and under; military, first responder, and educator discounts; student discounts; and “Southwest Nights” for those living and working in the District’s Southwest neighborhood. To learn more, visit arenastage.org/savings-programs.

Running Time: Two hours and 40 minutes, with a 15-minute intermission.

The We Are Gathered program is downloadable here.

COVID Safety: Arena Stage recommends but does not require that patrons wear facial masks in theaters except in designated mask-required performances (Tuesday, May 27, 7:30 p.m., and Saturday, June 14, 2:00 p.m.) For up-to-date information, visit arena stage.org/safety.

SEE ALSO:

You need to see how ‘We Are Gathered’ at Arena celebrates Black queer love (review by Gregory Ford, My 25, 2025)