Remembering a divide

In the fall of 2019, two plays opened on Broadway written by gay men of color. The first was Jeremy O. Harris’ Slave Play, transferring from a hit off-Broadway run. The Black writer made a provocative work set in the antebellum South, staging sexual submission scenes with enslaved people — before taking a wild turn, and engaging with power dynamics between interracial couples in the present day. The second play was Matthew López’s The Inheritance, transferring from an award-winning West End run. The Puerto Rican writer created a two-part, seven-hour epic. López translates E.M. Forster’s 1910 novel Howards End into a 2010s New York City, to explore the enduring influence of the AIDS pandemic in gay America.

In subject matter, Harris’ and López’s shows overlap. Both reveal how physical diseases create psychological trauma, arguing that historical events terrorize the present moment. Both works are also very gay, staging group sex scenes with a frank, subversive pleasure.

Yet in mood, Slave Play and The Inheritance are worlds apart. Harris writes what he calls an “exorcism,” challenging audiences with racial and sexual violence, and showing uncrossable divides between lovers. Slave Play aims to disturb, but The Inheritance aims for catharsis. López challenges audiences with beauty: characters monologue about caring for the sick, and the play’s coup de théâtre includes a resurrection of dead bodies miraculously healed. The racial makeup for each play’s Broadway production should be noted, too. Slave Play had an equal number of Black and white/“white-passing” cast members. The Inheritance had actors of color in smaller roles, but every main character was played by a white man.

In the fall of 2019, I was a junior in college studying theater, and the buzz around both shows was inescapable. I saved up some of my RA money to see Slave Play on Broadway, and left feeling devastated. The queer interracial relationships onstage felt uncomfortably familiar to my own experiences in Virginia. I hadn’t saved up enough money to also catch The Inheritance, but I ordered its playscript as soon as it was published.

On the page, I appreciated López’s detailed prose and melodrama, but The Inheritance didn’t sweep me away with emotion. Its knowing portrait of upper-class, millennial NYC felt unwelcoming. This was a gay world I knew existed, but to me as a Gen Z reader, it had little to do with the gay community I was living in. When I saw production photos of The Inheritance, they resembled Provincetown Instagram posts: attractive and sun-kissed, but insular and homogenous.

The differences between Slave Play and The Inheritance also reflected a growing divide I felt in gay academia. Slave Play aligned with a specifically Black movement led by scholars like Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, L.H. Stallings, and Frank B. Wilderson III. These writers acknowledge that Black Americans have never been treated as “human,” so these writers reject that label and slyly embrace submission and non-human modes of being. The Inheritance instead aligned itself with José Esteban Muñoz and Tavia Nyong’o: writers exploring how gay culture can create hopeful, utopic spaces of belonging through memory and imagination. Both sides of queer scholarship felt oppositional to each other. One undid the idea of belonging at all, and the other affirmed new spaces of belonging. The debate demanded I pick a side.

In a way, I chose Slave Play’s side. The year 2019 was a time when the Trump administration was wreaking havoc on American institutions, so Slave Play boldly intervened into American storytelling (joining other Black playwrights and journalists of the time). Harris’ play matched the zeitgeist of Gen Z teens looking for disruption. So as I developed my journalistic practice, I extensively covered Slave Play, championing it as a work truly of our times, a play openly exploring my biracial and Virginian identities.

Yet in many ways, the rest of the world chose The Inheritance’s side. The Broadway production spoke to the Gen X gay men who lived through the height of the AIDS crisis. The Inheritance definitively triumphed at the 2021 Tony Awards, winning four awards, including Best Play. In that same ceremony, Slave Play was nominated for 12 awards, making it the most Tony-nominated play in history up to that point. Slave Play also lost every nomination, a fact that still feels pointed to me. It seemed like the world saw two differing versions of queerness: one brutal and eviscerating, the other optimistic and comforting. The world picked the latter option, and has since seen The Inheritance produced across the globe.

The Inheritance has now arrived closer to my hometown, at Bethesda, Maryland’s Round House Theatre (where it’s playing through November 2). Today, I’m different from my 2019 self — as I’ve written about in this publication, I’ve now participated in the affluent NYC culture that once intimidated me, and traveled into queer adulthood. The Round House production presented a unique opportunity to reconsider The Inheritance from a mature perspective.

When going to both parts of the Round House production, I tried to let go of any assumptions or biases I had about the play itself, and watch with an open mind. This revival delivers incredible performances and exquisite direction, but I still found The Inheritance to be a flawed play that doesn’t successfully engage with gay history. This Round House production does, however, achieve something far stranger for me. This show convinced me that both The Inheritance and Slave Play aren’t the best way forward for queer theater.

Watching with appreciation and fear

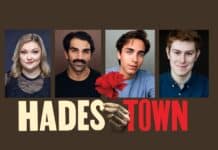

This Round House revival demands a closer inspection of the play’s plot. The Inheritance opens with a group of young gay men sitting on stage, hoping to write a story about their lives. One young man (played by Jordi Betrán Ramírez) returns to his favorite novel Howards End, thus summoning the presence of its author E.M. Forster (Robert Sella). The rest of the play unfolds as a communal retelling of Howards End, with the ensemble speaking in assured third-person narration to the audience.

The Schlegel sisters, the protagonists of Howards End navigating romance and class in England, have become an American gay couple. It’s 2015, and Eric Glass (David Gow) is celebrating his 33rd birthday party in his spacious Manhattan apartment, which is also about to lose its rent-controlled status. He lives with his partner, Toby Darling (Adam Poss), a snarky but endearing novelist who’s adapting his writing for the stage.

After some intense sex, Eric and Toby decide to get married. But two chance encounters with other gay men set off a chain of developments. First, the recent college graduate Adam (also played by Ramírez) arrives at Eric’s party to retrieve a mistakenly-swapped tote bag — and soon joins the friend group, even auditioning to play the lead in Toby’s play. Then, Eric starts forming a friendship with the ailing Walter Poole (also played by Sella), an older gay man married to the wealthy businessman Henry Wilcox (Robert Gant). Walter tells Eric about his romance with Henry: they found each other just before the AIDS crisis hit New York City, and escaped to an upstate house to avoid being surrounded by death. Yet Walter would use their home to care for his dying friends, leading to a strained relationship with Henry.

As an adaptation of Howards End, The Inheritance is very shrewd. López tackles the central theme of the novel — what responsibilities we owe to strangers, family, and lovers — and grounds it in the millennial generation of gay men. It’s a generation that has tangibly benefited from gay liberation movements, but one that still can’t shake oppression. By making all but one of his characters gay men, López can better dramatize connections between all the story’s characters. The Inheritance’s web of friendly, romantic, and sexual situationships is one I find accurate to modern queer life.

Director Tom Story excels when utilizing the large ensemble of this Round House production. The image of gay men gathered together recurs throughout the show — yearning individually, but connected physically. Each time that image appeared, it took my breath away. Story also encourages his ensemble to perform narration with a steady demeanor, emphasizing the show’s metatheatricality. I’m reminded of the gay film critic Parker Tyler, who wrote in 1944, “The [film] spectator must be a suave and wary guest, one educated in a profound, naïve-sophisticated conspiracy to see as much as he can take away with him.” At its best, The Inheritance feels like López’s witty conspiracy to take away as much from Howards End as possible. This ensemble likewise makes the audience feel like we’re part of a suave in-crowd, seeing everything gay NYC offers.

Yet for most of The Inheritance’s runtime, I could feel Story (and this Round House production) working overtime to massage the play’s flaws. The most consistent critique of the Broadway production was that despite the play being written by someone of Puerto Rican descent, The Inheritance’s cast was too white. López defended himself in 2020 by stating, “Eric Glass, my central character, may be a white man, but he is a white man who was created by a Puerto Rican one. That has fundamentally informed his journey through the play.” It’s a valid rebuttal, one I’ve seen playwrights of color Branden Jacobs-Jenkins and Larissa FastHorse make while defending their Broadway shows led by white actors. What these playwrights fail to address is that productions about people of color aren’t often produced at the same level. It’s because Eric Glass is white that he can journey to Broadway.

Thankfully, the cast of this Round House production is much more diverse, adding dimension to the play’s social mobility narratives. When the actor of color Adam Poss plays Toby Darling, suddenly his search for wealth makes more sense to me. In Toby, I recognize my own Asian American family members who think succeeding under capitalism will end their feelings of alienation. Looking through the playbill, I also discovered that Ramírez previously played B in Sanctuary City. That play stressed how safety can feel maddeningly arbitrary in America, and that same idea also animates Ramírez’s characters (Young Man 1, Adam, and later Leo).

Still, these resonances for audiences of color are all subtext. López writes with detail about Eric’s German immigrant family, but doesn’t offer that same specificity to Toby’s family. In fact, Toby’s character arc is a textbook definition of the trauma plot: for nearly six hours, López dangles Toby’s horrific backstory in front of the audience like a carrot on a stick. When López finally gives us the backstory, he’s hoping to provide justification for all of Toby’s anger, and to deliver a wallop of pathos. I mostly felt manipulated. Toby didn’t feel like a real person, just a sentimental, tragic archetype.

That’s the same problem facing Leo — a poor, Gen Z sex worker who makes a treacherous journey through NYC. Still, Ramírez delivers a heartbreaking performance as the character, conjuring an intense daze of desperation. It’s through Leo that López writes most incisively about the AIDS pandemic. “He thought of the chain of infection that had been passed along the years,” Leo states, “decades and generations, his particular lineage moving from person to person, until it was eventually passed to him. A bitter inheritance. And yet, despite this chain of humanity, Leo never felt so alone in all his life.”

Deep into the show’s second part, these lines made my ears prick up. Even if Leo was an archetype, maybe he would speak up for truly marginalized Americans. But just as Henry Wilcox retreats into his wealth to escape the AIDS pandemic, López retreats into his wealthy characters and away from his poor, HIV-positive ones. Leo is granted a few moments of delicate feeling, but The Inheritance is far more focused on cataloging bespoke restaurants, dazzling art performances, and opulent apartments. Within this epic is nearly an hour of Vogue-esque lifestyle writing.

This writing reveals López’s ownership over NYC, one he sees as hard-earned. In a 2019 New Yorker profile, López shared his sadness at having been raised in Florida, stating, “I feel like what was taken from me without my consent — before I was born — was my birthright, which was being a New Yorker.” López’s attitude reminds me of Jeremy Atherton Lin’s book Gay Bar: Why We Went Out, wherein Lin recounts a 1990s gay San Francisco reeling from AIDS but also doubling down on gentrification. “I’d imagined that homos moved to the city out of rebellion,” Lin writes. “I hadn’t considered entitlement as a motivating factor.” López’s entitlement fuels The Inheritance. Although the playwright has dramatized NYC’s changing neighborhoods, here López doesn’t explore gay men’s status as harbingers of urban displacement. The Inheritance itself sometimes feels like a work of gentrification, of sanitized luxury. López wants to show wealthy gays in all their splendor, bitchiness, and beauty.

The song can’t last forever

Beauty, more than anything, is the goal of this production of The Inheritance. Tom Story encourages us to appreciate the male form; Colin K. Bills’ lighting design bathes actors in exquisite colors; Lee Savage’s scenic design includes gorgeous cherry blossoms. Historically, AIDS narratives have been tragedies rendered ugly and stomach-churning. The Inheritance offers a corrective of sorts, envisioning a gay future of sun-dappled beauty.

Yet after hours of tasting The Inheritance’s sweetness, I wondered where Leo’s “bitter inheritance” had gone. In 2018, writer Doreen St. Félix critiqued the film adaptation of If Beale Street Could Talk, arguing that the film’s beauty sanded down the rough edges of James Baldwin’s original novel. When I’m feeling most cynical, this is exactly what I see López doing to the AIDS pandemic. It’s ironic that Washington, DC is an important site of gay activism, but none of that energy is captured in this DC production. Watch the documentary How to Survive a Plague and you’ll see ACT UP protesters putting red dye in fountains to make them resemble blood, chanting, “Bringing the dead to your door, we won’t take it anymore!” and spreading the ashes of AIDS victims on the White House lawn.

I don’t expect every AIDS narrative to stage polemic moments like that. Still, it’s telling that López felt obligated to include activist characters in The Inheritance, but didn’t fully explore them. Black characters like Jason #1 (John Floyd) and Tristan (Jamar Jones) reference the double standards Black and transgender people face in the LGBTQ community. But they mostly state statistics, serving as human virtue signals not woven into the larger arc of the show. The play’s sole leftist character, Jasper (Hunter Ringsmith), is similarly underwritten. Jasper keeps bringing strained identity politics into his capitalist critiques — and while some 2010s activists certainly did this, I just don’t buy that this middle-aged character would make those mistakes. Jasper feels like a straw-man López writes just so that a billionaire gay man can tear him down. The Inheritance hints at disturbing histories in the gay community — but the play ameliorates those histories with flowery writing. Similar to the AIDS Memorial Quilt, The Inheritance sometimes smothers horrors under a fastidious beauty.

I’ve loved this kind of beauty before. The Inheritance reminds me of Sufjan Stevens’ song “The Only Thing” (coming from Stevens’ album Carrie and Lowell, a stunning reflection on his mother’s death). In the song, the narrator encounters the dangers also faced by Toby and Leo: addiction, self-harm. The only thing protecting him? Beauty. He recalls constellations of stars, animals in nature, and his mother’s face. When the narrator asks “Should I tear my eyes out now, before I see too much?,” it’s because the world is too beautiful to bear.

When I’ve been at my lowest, I’ve needed this message. “The Only Thing” has sometimes been the only thing stopping me from harming myself. Stevens’ voice reminds me there’s so much wonder in the world. Recently, though, Stevens has disavowed this message. For the 10th Anniversary Edition of Carrie and Lowell, the singer-songwriter wrote an essay stating that this music was an unhealthy way to grieve:

I could never make sense of the nothingness that consumed me, and it was foolhardy to believe anything good could come of superimposing my mother’s memory onto my music in the first place. But I did it just the same. And the result was a hot mess. For the first time in my life, I was faced with the limitations of a creative process that exercised exploitation and exhibitionism as expressions of personal truth. My music failed me.

When I watch The Inheritance, I see a similar “hot mess” of art and grief. Both López and Stevens transform suffering into an almost holy tableau, but fail to truly understand their pain. Just as Stevens superimposed his mother’s death onto his music, López superimposes the entirety of the AIDS pandemic onto his drama. He’s created a redemption fantasy for the dead so gorgeous it threatens to mask the agony of the people who were (and are) victims of the AIDS pandemic.

The Inheritance is beautiful. But that beauty comes at a terrible cost.

Who shall inherit the stage?

I’m not the only person of my generation who feels this way about The Inheritance. I’ve spoken to multiple gay friends my age who saw the play’s Broadway production, and they all arrived at the same conclusion: this is history we want to remember, but maybe this specific play isn’t the best way to restage it. The creative team behind this revival cares deeply about passing along this play to subsequent generations, but The Inheritance already feels like a dated 2010s period piece. The play’s epilogue, written for a future 2022, now takes place in the past.

The six years between the 2019 Broadway production and this 2025 Round House production have felt like a lifetime. But it’s a lifetime where, as the recent film One Battle After Another puts it, “very little has changed.” The COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement promised transformational changes to society, but those changes are now erased from existence by the second Trump presidency. Just like in 2019, The Inheritance feels overly optimistic in the face of destruction. In The Inheritance, there’s little discussion about political strategies to resist Republican administrations; gay men find solace only through individual acts of kindness.

If anything good has come from discourse around The Inheritance, it’s that queer writers are now more conscious of the politics shaping their stories. Joel Kim Booster’s rom-com Fire Island also translates a classic novel of manners (Pride and Prejudice) into the gay community. But thankfully, Booster properly explores divides across race, class, and body type in his film. Steven Phillips-Horst’s article “We’ve Reached Peak Gay Sluttiness” also lovingly catalogues a sexually liberated friend group, yet with a keener eye for the influence of capitalism and technology.

Dramatists are also filling in the narrative gaps that López missed. The Inheritance only features one woman character: Margaret, a mother who discusses caring for her sick son. Yet Paula Vogel’s Mother Play, being staged by Studio Theatre next month, offers more multidimensional women. Drawing on her own experiences caring for a brother who died of AIDS, Vogel writes more candidly about the physical demands of care labor, and creates a detailed look at homophobia within the DC community. Even Drew Droege’s play Messy White Gays, currently in previews in NYC, seems to more directly address race and entitlement.

Nowadays, I feel ambivalent about both López’s work and Slave Play. For years, I’ve approached Slave Play from a defensive stance: no regional theater in DC has staged Harris’ work, a sign to me that it’s not considered “palatable” enough for DC audiences. But Slave Play and The Inheritance now seem like two theatrical extremes: one overwhelms me with cruelty, the other overwhelms me with beauty. Both are unsustainable to stage in the long run. And for me, both offer unsustainable political practices, for both queer theater and queer life. I can’t feel devastation or catharsis all the time.

If there’s one play I’ve seen that synthesizes Slave Play and The Inheritance, it’s Jordan Tanahill’s Prince Faggot (now running in NYC’s Studio Seaview). The show opens similarly to The Inheritance: a group of LGBTQ actors gather to reminisce on their queer childhoods and the culture that’s shaped them. Tanahill’s show then imagines what would happen if a future heir to the English throne was a gay man, with the six-person ensemble playing multiple roles.

Just like López, Tanahill is invested in what responsibilities gay men have toward strangers, family, and lovers. Similar to The Inheritance, Prince Faggot is an ambitious epic, spanning decades of history, exploring what’s inherited across generations of gay men. Yet Tanahill’s work also picks up on the best parts of Harris’ Slave Play. Prince Faggot is unafraid to shock its audience with intense kink and sex. The show also investigates the uncrossable divides in interracial relationships, staging the horrific legacies of the United Kingdom’s colonialism.

The show’s most ingenious moments are also its most affecting. After scenes about the royal family, Prince Faggot’s actors will seemingly break the fourth wall, delivering part-fictional, part-real monologues to the audience. After a sex scene, Rachel Crowl shares a bold story about watching that scene in rehearsals, feeling a mixture of admiration and jealousy as a trans woman. After a parade scene, N’yomi Allure Stewart talks frankly about not caring about the royal family unless Black people like Meghan Markle are involved. She discusses NYC’s ballroom culture and the need for queer people to create their own monarchs.

Crowl and Stewart deliver powerful, personal interventions into Tanahill’s play. The actors remind me of the interventions critics of color like me have made into both Slave Play and The Inheritance — but when Crowl and Stewart perform their monologues onstage, their criticisms felt so vulnerable that I started to tear up.

I hope that future productions of The Inheritance, and future dramatists writing about the queer community, will include some of the directness of Prince Faggot. That radical honesty might create more sustainable political practice. Radical honesty might create theater that’s even more beautiful.

The Inheritance plays through November 2, 2025, at Round House Theatre, 4545 East-West Highway, Bethesda, MD (one block from Bethesda Metro station). Tickets ($50–$108) can be purchased by calling 240-644-1100, visiting the box office, or online (Learn more about special discounts here, accessibility here, and the Free Play program for students here.) Tickets are also available on TodayTix (Part One) and (Part Two).

Running Times:

The Inheritance, Part One: Approximately three hours and 25 minutes, including two 15-minute intermissions.

The Inheritance, Part Two: Approximately three hours and 15 minutes, including one 15-minute intermission and one 5-minute pause.

The digital program for The Inheritance is here

Advisory: Photography and video are strictly prohibited. Upon arrival, patrons will be asked to place a sticker over the camera on their phones, and it must remain in place for the duration of the performance. (Stickers are residue-free and are easily removed at the conclusion of the performance.)