By Alan Abrams

How do you write a review of a stage play when one of its three characters was your closest friend? Your first responsibility is to acknowledge that you cannot be objective. But I think even if I had never known Carl Vogel, or his sister, Playwright Paula Vogel, or their sharp-tongued mother, I would have been held just as rapt by the performance as anyone else in the audience. By the same token, the performers each captured the essence of the people I remember. Their dialog — and their mannerisms — dispelled any reluctance to suspend disbelief.

The cast of three is not so much a triad as it is two points revolving around a hub. The action develops as Carl, the elder sibling, intervenes to support his sister, Martha (a stand-in for the playwright), from the negativity of Phyllis, their alcoholic mother. Phyllis recognizes the unique brilliance of her son, but strives to deny Martha any opportunity to flourish in her own right. Phyllis is determinedly antifeminist. Carl steps in with enthusiastic encouragement for Martha, lavishing on her his own library of feminist literature. This tension becomes a crisis as it becomes clear to Phyllis that her son is gay. A love-hate relationship is more powerful than either love or hate, because it imprisons its adversaries in their hellish connection. Carl is only able to break free of his mother in his final years, not long before becoming another victim of the AIDS holocaust.

What the play demonstrated to me was how little I really knew about Carl’s family. Even though we went to the same schools, I barely knew Paula. My only firsthand memory of her was from an afternoon in Carl’s bedroom, during the winter of 1965–66. I know the year, because I had hitchhiked to their Erie Street apartment with a freshly issued copy of The Beatles’ Rubber Soul album. It must have been a snow day, but Phyllis was at work. Carl and I played the album — probably several times — before Paula quietly appeared with her gut-string guitar. I don’t recall Carl summoning her. Sitting on the floor, cradling her instrument, she played and sang a perfect rendition of Leonard Cohen’s “Suzanne,” probably cadged from Judy Collins’ haunting version.

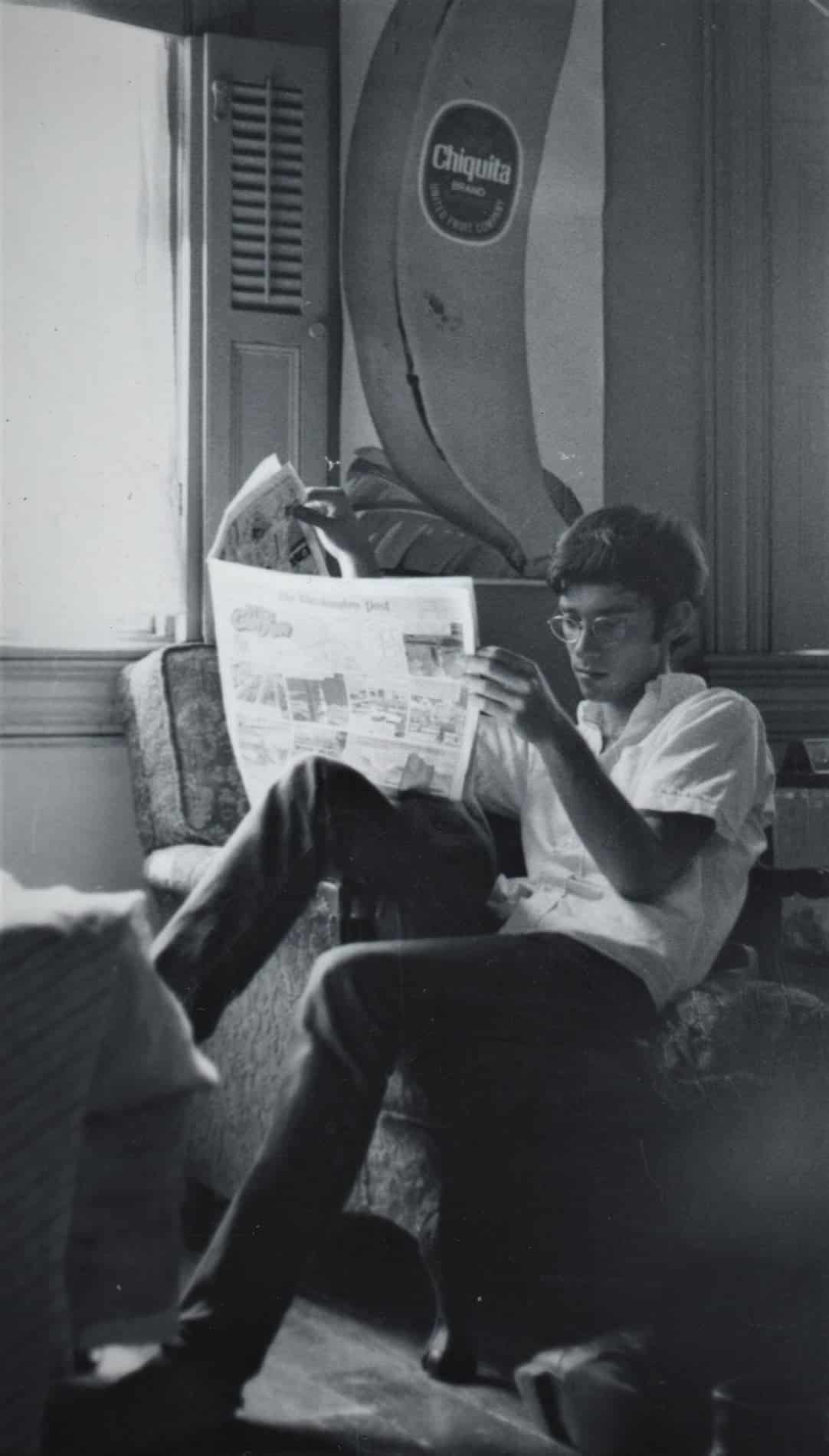

How easy it is to fall in love when you are barely 16, when some part of you is already in love with this girl’s brother — however suppressed that love might have been. But something told me to let it go, that to pursue any connection with this desperately cute, kitten-like adolescent, with her lovely plump fingers and her angelic voice, was somehow taboo. Did I perceive, subconsciously, that Paula was a chrysaline lesbian? Was she herself fully aware of her sexual orientation? And what was it that impelled her that snowy afternoon to share a song with her brother’s gangly, myopic friend — so inferior to her brother’s prodigious intellect, and so often the victim of his witty skewerings?

I think Carl did not want to share too much of his dysfunctional family life with me. Maybe it was out of shame, or maybe it was because, as the play reveals, he was the adult in this troubled family (in vivid counterpoint to his mother, crippled by her dependence on gin, and on the illusion that she was still a beautiful, desirable party-girl), and he wanted to spare me the burden of suffering along with him.

The play also illuminated the antipathy for homosexuality that I grew up with. Not long after we met, Carl came to my home for a visit. After he left, my father said, “That boy is a sissy.” The meaning was clear, and it infuriated me. Of course, he wasn’t — or so I believed — all, he was so popular with the coolest girls. That illusion persisted until we graduated high school, and I learned of his male amours. (If there was still any doubt, it was shattered when I tried to bed him myself. It turned out to be a miserable failure — disappointing us both — but also confirming my own heterosexual identity.)

My connection to Phyllis was as slender as it was with Paula. My only recollection of interaction with her was when my wife and I, and our infant daughter, visited Carl when he was between semesters at Johns Hopkins. My wife Linda and I were still teenagers. I can’t remember Phyllis’ exact words, but they could have sprung from Paula’s script: Phyllis ridiculing me for impregnating my girlfriend right after graduating high school — and worse — my foolish willingness to “make it right.” Of course, her message was well deserved — but it stung like salt rubbed in an open wound. I have no doubt Carl (who loved Linda no less than I did) rose to our defense.

After that, Carl and I grew apart. I saw him only a handful of times over the next 18 years, when he returned to Maryland, wasted by AIDS. He was fortunate to have the support of his father and older brother (who do not appear in the play), as well as another close friend from high school, during his final days.

I am grateful for Paula’s play, which keeps Carl’s memory alive. I hope that the writing of it, and seeing living humans embody these ghosts, eased her grief. Those of us who knew this remarkable man are a dwindling cohort, and some of us, like Phyllis, are also losing our memory. Tonight I will say a prayer for him, in the event that my disbelief in an afterlife is unfounded. If that is the case, I know Carl will be listening.

The Mother Play: A Play in Five Evictions plays through January 4, 2026, in the Mead Theatre at Studio Theatre, 1501 14th Street NW, Washington, DC. For tickets (starting at $42), go online, call the box office at 202-332-3300, email boxoffice@studiotheatre.org, or visit TodayTix. Studio Theater offers discounts for first responders, military servicepeople, students, young people, educators, senior citizens, and others, as well as rush tickets. For discounts, contact the box office or visit here for more information.

Running Time: 90 minutes with no intermission

The program for The Mother Play is online here.

Alan Abrams took up writing after a long career in building and architecture. His poetry and short fiction have been widely published in journals and anthologies in the U.S., UK, and Ireland. In 2024, Abrams founded Sligo Creek Publishing, specializing in poetry, fiction, and memoir.

SEE ALSO:

Gay siblings and a flawed mom make do in ‘The Mother Play’ at Studio Theatre(review by Amy Kotkin, November 18, 2025)