Decades after the deaths of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, their books remain beloved. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia and Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings have been translated into dozens of languages and adapted for stage, film, and TV. Both Lewis and Tolkien spent much of their careers at Oxford University, where they met each other and spent the better part of two decades gathering regularly in university rooms and in pubs, sharing friendship, laughter, fierce debates, and drafts of works-in-progress with their informal literary circle known as the Inklings. Both Lewis and Tolkien openly acknowledged the influence of the other on their work, and their most famous and enduring fantasy works owe much to the encouragement and critique that the two writers shared with one another.

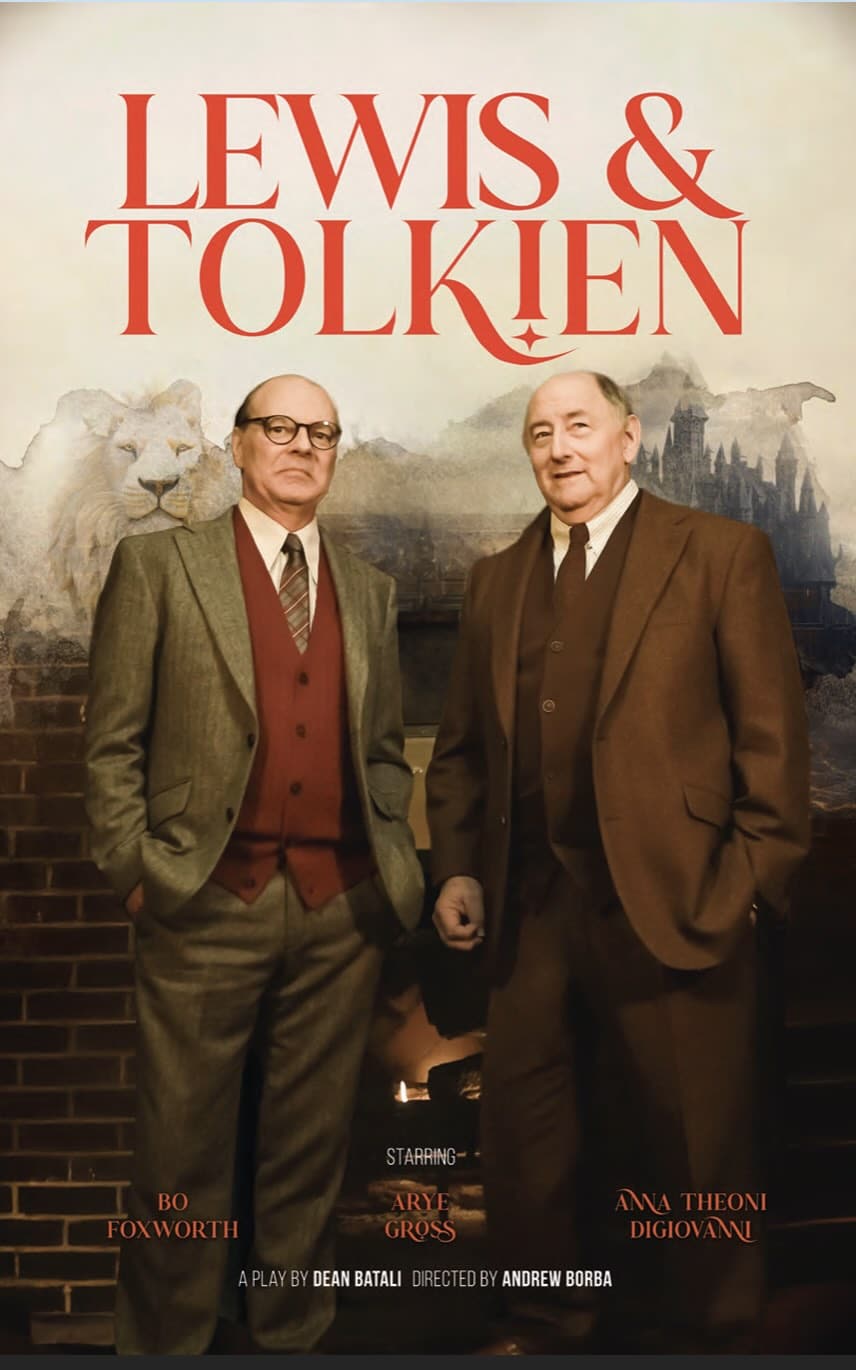

Now playing at the Museum of the Bible’s World Stage Theater, Lewis & Tolkien provides a window into the creation of these fantasy worlds and into the flawed, complex, and deeply human individuals who wrote them. Written by Dean Batali (best known for his work writing for TV, including Buffy the Vampire Slayer and That ’70s Show), and originally performed at the Actors Co-op in Los Angeles in 2023, Lewis & Tolkien imagines a late-in-life reunion between the two authors at the Eagle and Child Pub in Oxford (a favorite haunt of the Inklings in the 1930s and ’40s), after nearly a decade of separation.

Director Andrew Borba and actors Arye Gross (Tolkien), Bo Foxworth (Lewis), and Anna Theoni DiGiovanni (Veronica) recently sat down with DC Theater Arts on the set of the show to discuss the play and the longstanding real-life friendships behind it — both the historical friendship between Lewis and Tolkien, and the present-day friendships between several of the individuals involved in the production. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Hannah Estifanos: To start, can you share a bit about what drew you to this production, or anything about its origin story?

Andrew Borba (Director): I got a call from Dean Batali, our playwright, whom I’ve known for a long time. This play has brought up so many feelings about long-term friendships and fellowship, how to maintain them, how beautiful they are, and how deep. That has been just profound. So, Dean called and said that both he and Marc Whitmore, who is producing it, were interested in bringing it to the Museum of the Bible, and would I be interested in throwing my hat in the ring to direct it? I was like, absolutely. I had seen Dean’s production in LA and thought this is a great play. So then we just started talking and working.

How about you all as the cast? What drew you to become involved?

Arye Gross (J.R.R. Tolkien): Well, I got a call from Andrew. We had worked on a production about 10 years ago of Uncle Vanya and played great friends. And Andrew gave me a call and brought me on board.

Bo Foxworth (C.S. Lewis): Very much the same. Andrew sent me an email out of the blue, and asked me if I wanted to do it and I read the play and I was like, yes, because I’m a huge fan also of Tolkien and C.S. Lewis and they were the main stories I read to my daughter when she was young. So I was interested not only because of that, but also because the play is so beautiful and I could barely get through without weeping, just reading it.

Anna Theoni DiGiovanni (Veronica): Well, I live in DC right now, but my friend studied with Andrew at UC Irvine and recommended me, and I did a little Google sleuthing as we all do, and I realized that I knew who [Bo and Arye] were from when I lived in LA and I admired their work. It is just really lovely to be in a space where you can look at artists whose work you admire and grow and learn.

Arye and Bo, this next question is for each of you. What did you learn about Lewis and Tolkien as you prepared for your roles? Was there anything that surprised you about the characters you’re playing?

Arye: I mean, how long do you have? There’s so much. I knew relatively little about either of the men, though I had read some C.S. Lewis, but not much Tolkien. [Bo and I are] rooming together and every day I’ve got another bit of “Tolkieniana” just discovered from reading his letters or something like that. It’s rather extraordinary. One of the things I’ve learned is how much Lewis — and it’s stated in the play — was an influence on Tolkien, and how much advice and counsel and criticism he gave him as he was writing The Lord of the Rings.

Bo, how about you, inhabiting the role of C.S. Lewis?

I had never really looked into Tolkien or Lewis as writers. So when I read this play, I had heard some things about Tolkien and how World War I influenced some of his writings of The Lord of the Rings, but I didn’t realize what good friends they were, how close they were, and how much they influenced each other. And Tolkien was a huge influence on Lewis and though he’s known as the apologist, it’s really Tolkien that brought Lewis back to Christianity, an atheist after his mother died. And it was Tolkien who changed his thinking and really changed his life in a lot of ways. It was after that that he was able to incorporate religion into his subcreations, his stories. [Here the two actors slip into character and start riffing off the play:] “And though he may not have been the biggest fan of my writing, they still had a great friendship for many years until his Catholicism got in the way…”

Arye: “Or one could say that your Protestantism doesn’t quite get you there.” [Laughs]

Anna, as Veronica, who is a fictional barmaid in this play, what does your role bring to the story of Lewis and Tolkien, and how do you make her your own?

So much of Veronica is being built off the genius of the two of them. The joy of playing Veronica is to come in with an open mind and not judgment, and be surprised and delighted by every single thing that these gentlemen bring to the table, not only as Tolkien and Lewis, but as Arye and Bo. I think what I’m learning, and Veronica’s learning, is that if you release the expectation, you’ll be so surprised by where the journey is going to take you. And I think that is Veronica’s journey in this play, too. She comes in with this expectation of her workday and by the end of it, she’s — no spoilers — open to new adventures.

We’ve talked about reading the works of Lewis and Tolkien, and they’re so well known for their fantasy. Their works have been translated into many languages. They’ve been adapted for stage and screen and so many different formats. I’m curious, what does this particular production add to the Lewis and Tolkien cinematic universe, if you will, that’s unique?

Andrew: First of all, this is a fictional representation of a meeting later in their lives that they didn’t have — an imagined meeting. And I think it actually salves an open wound that a lot of people perceive between these two writers. Maybe more to the point, and I’m just quoting Dean, our playwright, the title of the play is Lewis and Tolkien. So if you love those writers, you are going to love this play. But we also talked a lot in pre-production about how you don’t really need to. If you don’t know much about these writers, you will still love this play.

But what’s it adding to the lexicon? I think a deeper understanding of who these two gentlemen were on a human level and, as Bo said, they really are each a ladder for the other, because the depth of their work would not have been what it is without the other. They need each other, and needed each other, and that is the truth. That’s not imagined.

Arye: I’d say that as someone who is relatively unread, really with both of them and ignorant of their lives, even if you knew nothing and if Lewis and Tolkien never existed, the play also functions as a very profound portrait of an adult friendship that is at once profound and rocky. It’s two articulate, emotionally in-touch men who get into what real friendship is and also confront where things go off the rails and cop to it. That was the thing that really grabbed me by the heart when I read it.

Bo: We can barely get through a run without bursting into tears.

Arye: I tend to fall apart a lot, at least in rehearsal anyway. Hopefully I can rein it in in front of an audience.

Bo, is there anything you would like to add to that?

The portrait of friendship and fellowship that existed between these men is just really powerful in ways that people just don’t connect these days as writers and intellects. I mean, I wish this was a real meeting between the two of them because I think Lewis passed before they were able to really reconnect in the way they do in this play. And it’s so moving to me every time. It’s one of these plays that I, and it rarely comes as an actor, where I cannot wait to get back to rehearsal the next day because it’s just so enjoyable saying these words and being a part of this friendship, as rocky as it is, and seeing them come back together again. It’s heartbreaking that it didn’t happen.

In our time, much is being written about loneliness as an epidemic (and particularly among men) and about people becoming estranged because of their disagreements. How does this play, which is centered on Lewis and Tolkien and their time, speak into our time, where these challenges are perhaps even more acute?

Arye: There is a significant portion of the play that deals quite emphatically with these notions of isolation and disconnection, and the longing for connection and reconnection. And Dean expresses some ideas that I think are quite profound, that have to do with cherishing friendship and nurturing it, and the importance of the willingness to be vulnerable in a relationship.

Anna: How it parallels today is if you got off your phone, you don’t know what could happen. There’s something in the risk that it takes to step out of your comfort zone, talk to someone that you don’t know, or phone a friend that you haven’t talked to in a while and sit with maybe five minutes of discomfort for the gloriousness of the 20 minutes of reconnection.

Bo: Which is expressed directly in this play.

I’m curious, what excites each of you the most about performing this play here and now — in this venue, in this city, at this time?

Andrew: The word community happens a fair amount in the play. So there is a connectivity with what I understand the mission of this museum to be. I’m now tiptoeing onto a slightly divisive road, but there are some people who may be hesitant to come to the Museum of the Bible to see a show. And I think this is the perfect crossover play for them to come into a venue that they wouldn’t have necessarily stepped into. It’s about stepping into the room and talking to each other. And this is a perfect play that gives the example of bridging those divides. I hope that it does that.

Andrew, Arye, and Bo, you’ve all done a lot of work with film and TV, and Dean, the playwright, is also best known for his work writing for TV. I’m curious what the medium of the stage offers that is unique and different from film or TV.

Anna: Well, but also these are greats of the theater. [Arye and Bo laugh.] I’m serious! When I was in LA as a wee undergrad, I knew who these guys were. They’re fantastic and they’re well-versed classical actors. And I firmly believe if you can do the classics, you can do anything.

Bo: It’s obviously the connection with an audience. I mean you can’t help but feel the energy of a large amount of people sitting out in front of you and the immediate response to something that’s being said in the moment. Whereas television and film is a lot of just hurry up and wait, and you can do multiple takes and you don’t have to get it perfect the very first time. Here, you don’t have a “back to one, take two!” But it’s that energy and connection with an audience and that immediate response that is so powerful and so intoxicating for me as an actor. I’ve been a theater actor my entire life and film and television has been kind of the peripheral. I just love that relationship between audience and [actors] — and it’s different every time.

Arye: But just to echo that, there is something specifically human about the fact that we’re all in the same room together and just as all of us on stage are entering a kind of communion with one another, there is a communion between the people who are standing on the stage and speaking and the people who are sitting and watching. Why is it that somebody watches characters in fiction on stage and they’re moved to tears? Because we’re primates, and when we see something, we experience it as though we’re living it. All this human interaction is happening — and if we lift our chins a bit, they’ll be involved as well, there in the balcony. [Laughs.]

Anna, you brought up the classics, which is a great place to come full circle and end on. You all have experience with Shakespeare and the classics. What do Lewis and Tolkien, speaking from their time, and both steeped in mythology and classics, have to say to us today about the power of story and mythmaking?

Anna: That’s the last third of the play! What’s lovely about the classics and lovely about [Lewis and Tolkien’s] work is that there are these permanences of humanity, no matter what century you’re in, that we will always feel and relate to. It’s fascinating that they talk about the classics, mythology, then Jesus, then fairytales, and then their stories. And then here we are doing the exact same thing and nothing has changed about humanity. Andrew said this the other day, that even in [any other] era they were still humans, they still operated the exact same way. Just there were different constraints upon them. And so I think revisiting the classics and revisiting these guys, we see that we’re actually not as far away as we might think.

Andrew: Not to take us too far astray, but I feel the same way about Shakespeare. Shakespeare is put on a pedestal as something unattainable or other than. And I find it to be exactly the opposite. What you find in a Shakespeare play is the humanity. That’s why those plays have lasted, not because we’re interested in Elizabethan England. Nobody cares about pumpkin pants anymore. But the point being, why are those stories so good? What is happening is this brilliant playwright has put people into specific circumstances with each other and they have to figure it out. I’m sort of shocked at how often I’ve referenced Shakespeare while we’re working on this play.

Anna: And those words bring a tangible word or phrase to the wordless. There are reasons why we quote [Shakespeare]. It’s because we can’t express what that feeling is without using those words. That’s why those things still last. And it’s fascinating. You even requote it in the play, but when you’re talking about myth and you say, well, it’s just truth breathed in silver, and that is a phrase that is so true, that will be repeated centuries on if it can. That’s why we revisit the classics, because they bring words to this wordless feeling that we all feel.

As we close, is there anything else that we haven’t brought up or haven’t asked that you would like viewers to know prior to attending the show?

Arye: There’s no intermissions. [Everyone laughs.]

Bo: So don’t drink too much water or coffee.

Arye: And please turn off your cell phones as we did not have cell phones in 1963.

Andrew: I have something, but it’s a little bit of a pitch. The tenor of what you’re feeling here amongst this group has been true all the way throughout, and I think comes through in the show. You have some master actors doing some master work on a story that is exceptionally beautiful. It’s articulate and personal and profound, and it’s just amazing. People should come see this because of these three actors. They should come see this play because it’s deeply moving and fun. It is as playful as clearly these people [are]. So this play is not a lecture experience.

Bo: There’s a lot of humor in it. And if you’re a fan of these two writers, you’ll get a lot of the humor that maybe others wouldn’t.

Lewis & Tolkien plays through November 30, 2025, presented in association with MWO Management, performing at the World Stage Theater on the fifth and sixth floors of the Museum of the Bible, 400 4th St SW, Washington, DC. Performances are on Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays at 7:00 pm, Saturdays at 2:00 pm, and Sundays at 3:00 pm. Tickets ($35–$59) are available for purchase online, at the Museum, or by calling (866) 430-MOTB.