Editor’s note: Woolly Mammoth Theatre, in conjunction with its staging of Jackie Sibblies Drury’s Fairview, has brought to DC a show produced by the Harlem-based Movement Theatre Company that is specifically by, about, and for Black people. Titled What to Send Up When It Goes Down, the work was written by Aleshea Harris in response to racialized violence. Part ritual, part audience participation, part play, and part celebration, What to Send Up was performed at three different venues—Duke Ellington School for the Arts, Howard University, and THEARC—on its way to a run at Woolly, now to November 10, 2019. Senior Writer and Columnist John Stoltenberg reports on each of the four tour stops.

Stop four: Woolly Mammoth Theatre, October 30, 2019

This powerful ritual of Black grief, anger, and love arrived last night in full force at Woolly Mammoth Theatre, where it will be performed only until November 10, 2019, as a living, uplifting memorial to lives lost to anti-Black violence. Nothing before seen on a major DC mainstage has been so deeply personal, so profoundly moving, and so unapologetically Black in its conception and celebration.

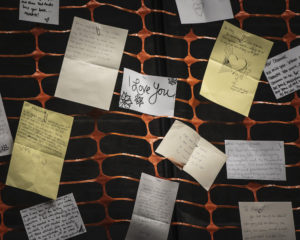

The stage of the Woolly theater has been stripped bare. The playing space with the ritual’s white circle extends to the wings and the back wall. Orchestra seating is supplemented by two rows of chairs on both sides. During vigorous episodes of step-dancing, the people seated on stage can feel the vibration of the cast’s pounding feet as if through their own bones. The orange safety fencing hung with love letters to Black people now sweeps around the entire circumference, with hundreds more hand-written notes than before. Coming from the ritual’s three smaller previous venues, it now seems monumental.

The intensity and authenticity of the cast members’ performance was undiminished. At times, as before, they were working from pain and rage. At all times as before they kept alive love. And even as the audience at this larger scale was more responsive than before—laughing loudly, for instance, during the absurdist satires of white privilege—the personal presence of the cast members seemed more expansive too.

At each of the tour stops I’ve attended, the racial ratio of audience members has subtly affected how the ritual is audibly responded to—a variable the performers seem keenly attuned to. Last night at Woolly, where out of about 90 people approximately three-fifths were Black and two-fifths were non-Black, reactions were definitely more voluble, typical of a more theatergoing crowd, and the cast kept faith with it without any loss of soul.

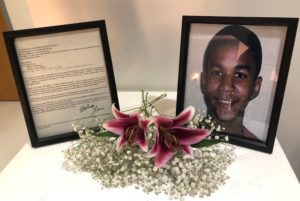

The pictures and memorials that have accompanied the tour are now in the Woolly classroom, and there are many more photos than before. Whereas at prior stops people have taken in this lobby display silently, somberly, almost reverently, last night at Woolly there was more of an outgoing, opening-night vibe.

In a lobby speech before people are shown into the theater, a cast member says:

Let me be clear: this ritual is first and foremost for Black people…. We are glad non-Black people are here. We welcome you but this piece was created and is expressed with Black folks in mind. If you are prepared to honor that through your respectful, conscientious presence, you are welcome to stay.

At no point have I observed among other non-Black participants anything but such conscientious respect. And though the transformational effect and emotional experience of the piece will differ depending on one’s race, from what I can tell from what people say during a go-round that is part of the ritual, What to Send Up When It Goes Down is having a deep impact on everyone who sees it.

Running Time: About 90 minutes, with no intermission.

What to Send Up When It Goes Down presented by The Movement Theatre Company will happen until November 10, 2019, at Woolly Mammoth Theater, 641 D Street NW, Washington, DC. Purchase tickets at the box office or online.

Stop three: THEARC, October 25, 2019

After runs at a high school (Duke Ellington) and a university (Howard), the DC tour of What to Send Up When It Goes Down traveled East of the River to the sprawling cultural and social services campus known as THEARC. There in the Black Box, the largest performance space on the tour so far, I witnessed the impactful ritual play to about 30 participants (with a racial ratio about four-fifths Black, about one-fifth non-Black). As on previous stops, there was a chalk circle in the center and love letters to Black people arrayed on orange plastic safety fencing on all four walls, but the increased height and expanse of the room meant more dramatic light cues and lent a kind of majesty and momentousness to the event.

There was also a generous context of hospitality. For all performances at THEARC, free meals were available—first come, first served, starting 90 minutes before showtime: bagged sandwiches, fruit, chips, and bottled water labeled DC Central Kitchen, the provider.

During the ritual itself, I became aware of subtle adjustments made by the cast to the larger space and smaller house. This audience was no less present and attentive than at previous tour stops but it was noticeably less vocal, so the cast was filling the space with their audible conviction—and at times their physicalized grief and rage—on everyone’s behalf. I surmised from the private tears I could observe that on this night the piece was happening for people with more interiority than unanimity. But it was no less powerful.

Now having seen the show three times, I have come to an enormous appreciation for how tightly directed and committedly enacted it is. What to Send Up seems absolutely real and true and in the moment, every time as if for the first time.

A little more than a year ago, during preproduction, Whitney White the director described on a Kickstarter video what the piece would be:

Why this piece now? It’s speaking loudly. It’s speaking unapologetically. It’s an experience. It’s not like anything you’ve seen before. It’s not like a traditional play. It’s a ritual that takes on very different aspects. It’s speaking boldly. It’s fierce. It’s fast. It’s nasty. It’s dangerous. And it shakes you. It’s talking about violence against Black bodies, violence that we’re all experiencing. Giving everyone that comes, if you’re willing and open,…a strategy to deal with the shit that we’re all going through. That will pull you in, suck you in, and take you on an amazing ride.

Whitney White foretold the show precisely.

Running Time: About 90 minutes, with no intermission.

What to Send Up When It Goes Down presented by The Movement Theatre Company will happen until November 10, 2019, at Woolly Mammoth Theater, 641 D Street NW, Washington, DC. Purchase tickets at the box office or online.

Stop two: Howard University, October 18, 2019

What to Send Up When It Goes Down is not a play. Nobody in it is playing. That became unmistakably evident when the Movement Theatre Company’s production happened in the Howard University Black Box Theatre—a space smaller than its previous venue but filled with the same number of people, about 60, closer in and closer up.

There is a script by Aleshea Harris. It has been published. The players follow it, word for word. But the text is to its enactment as liturgy is to sacrament.

Harris has said she never intended What to Send Up “to be treated like a play,” which makes it unlike anything else on stage in DC maybe ever. As Harris writes in a letter on display in the lobby:

I will always insist that this piece is a real ritual. The players aren’t pretending to be carrying out a ritual. They are in it. We are sincerely gathered to honor those who’ve been taken too soon….

As a ritual, it is meant to bring something into being: an event wherein Black people are invited to breathe, laugh, yell, feel joy, feel anger, bear witness, speak the names, commune, sing, see one another, and be reminded that we are seen and matter.

The racial ratio of the audience was approximately four-fifths Black and one-fifth non-Black. There were a good many Howard students in the house. And on this night the ritual became conspicuously cathartic—the word my colleague Ramona Harper used in her deeply moving and personal review of the work. There was audible audience response throughout, not just during the call-and-response portions of the script—indications of recognition and identification, utterances of affirmation. While I do not doubt that the experience of What to Send Up can be individually and personally cathartic for Black participants when not markedly in the majority, at Howard that catharsis became openly, publicly, collectively shared.

At points in the ritual a cast member will call out “Black people,” and the audience will call back “Yeah.” Repeated like an incantation, the exchange on this night became ever louder and more impassioned, like a long-suppressed shoutout to oneself and one another. And the same intensity of engagement was audible during the comedic bits—absurdist sketches featuring Miss, a ludicrous white lady in white gloves and pearls; Man, her shufflin and shuckin driver; and Made, her aproned housekeeper, who’s faking her cookin and cleanin and actually fixin for armed revolt.

One might not associate absurdism with Black-centric, Black-affirming ritual but Harris does. As she said in an interview with Huffpost:

Absurdist theater feels like home. Whenever I experience it, I’m like, well, that just makes so much sense to me…. Absurdism is a name for a way of responding to a world which no longer makes sense…. It dwells wherever there is trauma, and certainly there is trauma in the existence of black people in America.

On this my second opportunity to view and report on the What to Send Up DC tour, the function of absurdism in the ritual’s catharsis became palpably apparent, like a counterintuitive but profoundly political coup de théâtre. And it occurs to me I may have missed this resonance with real life the first time because I am not Black.

The players do not play-act. They follow Harris to the letter on that. What happens during What to Send Up is not so much actors performing as shamans divining. And at times what one witnesses seems to come from a depth of rage and anguish that cannot be attributed to any art but only sourced from life. Cast Member Rachel Christopher, for instance, has a long monolog as Made about the talk she wishes she’d had with her son before he was shot. And Christopher delivers Made’s words with such chilling and breathtaking vehemence as would be considered a showstopper if this were a show. But it’s not.

Running Time: About 90 minutes, with no intermission.

What to Send Up When It Goes Down presented by The Movement Theatre Company will happen until November 10, 2019, at Woolly Mammoth Theater, 641 D Street NW, Washington, DC. Purchase tickets at the box office or online.

Stop one: Duke Ellington School for the Arts, October 13, 2019

During an opening ritual on this Sunday evening, the audience was asked to speak the name of Atatiana Jefferson once for every year of her life before a white police officer shot and killed her in her home. About 60 people—about half of them Black, half of them non-Black—were gathered around a chalk circle drawn on the floor in the middle of the Duke Ellington School of the Arts blackbox theater. On the surrounding walls were lengths of orange plastic safety fencing hung with handwritten love letters to Black people. As the ritual leader counted from 1 to 28, the group’s voices intoned Atatiana Jefferson in unison—to honor a young Black woman who, the leader said, “was killed by an idea.”

A CNN headline the next morning said: “Former police officer found not guilty of murder in shooting death of unarmed black veteran.” As yet another dot got connected between real-life acts of anti-Blackness violence, it was as though the performance the night before was still going on.

In a conversation with Playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins for American Theatre magazine, Aleshea Harris spoke of her intention in writing What to Send Up When It Goes Down:

I knew this piece would have to do with Black people being killed by police officers with impunity. The idea was to hold people accountable, be confrontational, let it be messy, let it be angry, and let it tread as absurdly as the idea that a Black person could be killed on camera unarmed and the person who killed them get away with it. That is an absurd reality. I wanted to mirror that absurdity in the form of the play….

We’re mad and we have a right to be mad, because the gaslighting of anti-Blackness is: “You imagined that.” Or “It’s really about economics, not race.” There are so many ways people duck and dodge the uncomfortable reality that anti-Blackness is ingrained in the fabric of our country . I wanted it to be a no-gaslighting space.

The mood that night was somber, reflective, at times silent in sorrow, at times awkward during subversive skits about liberal-white racism, at times caught up in the vigor of angry foot-stomping dance. And always: no gaslighting.

People responded readily in response to requests for participation. At a point we all went around the room and said our first name. At another point we all went around the room and said a word for how we were feeling. But as the leader’s requests continued, an awareness became evident that many Black people present in the circle had experienced threats and assaults, including by an officer of the law, that the non-Black people there simply had not. That sobering consciousness of having come into the room from two differently raced places was never to let go. So it was that when we were asked to “share a group yell as a strategy for sharing our feelings about the untimely death of Atatiana Jefferson together as a community,” the full-throated yell that went out from everyone only seemed the sound of impromptu unanimity. For in fact throughout the performance there was the explicit understanding that, as one leader said,

It is not often that Black people have a safe, public space for expressing their unfiltered feelings about anti-Blackness. We are taking that space today.

That space created in grief and solidarity by What to Send Up When It Goes Down was openly owned by the cast and audience members who were Black and respectfully acknowledged by audience members who were non-Black. Such rare space will recur in town just 21 more times. To be in it, see information below.

Running Time: About 90 minutes, with no intermission.

What to Send Up When It Goes Down presented by The Movement Theatre Company will happen until November 10, 2019, at Woolly Mammoth Theater, 641 D Street NW, Washington, DC. Purchase tickets at the box office or online.

On tour in DC leading up to the Woolly Mammoth run, What to Send Up When It Goes Down was performed October 12 and 13, 2019, at Duke Ellington School for the Arts, 3500 R St NW, Washington, DC; October 17 to 20, 2019, at Howard University Black Box Theatre, 2445 6th Street NW, Washington, DC; and October 24 to 27 at THEARC West Black Box, 1801 Mississippi Ave SE, Washington DC.

Note that Woolly Mammoth Theatre has posted on its website a detailed summary of What to Send Up When It Goes Down, which contains numerous spoilers but may be helpful for anyone concerned or apprehensive about what the performance experience holds.