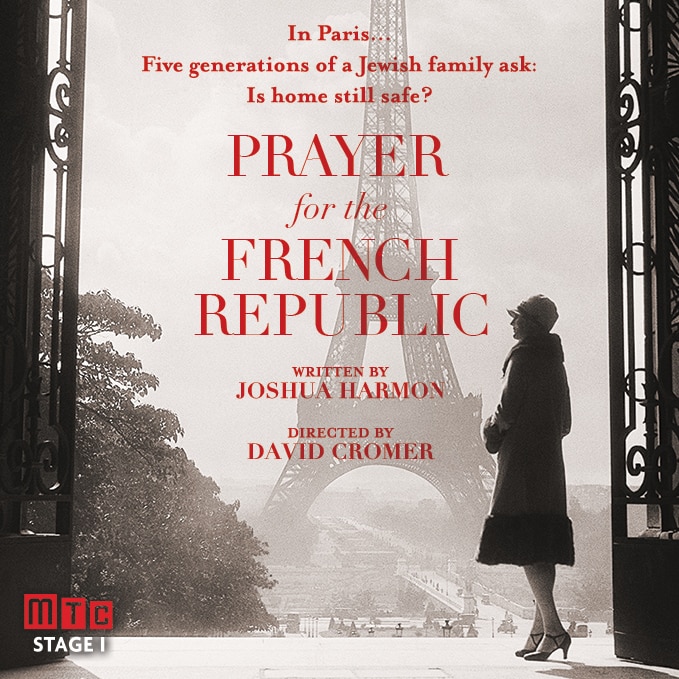

Manhattan Theatre Club’s world premiere of Prayer for the French Republic, written by Drama Desk Award winner Joshua Harmon (Bad Jews; Significant Other), directed by Tony winner David Cromer (The Band’s Visit), and commissioned by MTC through the Bank of America New Play Program, examines the traumatic effects of violent anti-Semitism across history through the lens of five generations of one Jewish family in Paris. Playing a limited Off-Broadway engagement at New York City Center through March 27, the fictionalized narrative, based on the playwright’s research trips and interviews conducted in France in 2016 (and on his own descent from French Jews, and as a student who minored in French and studied abroad there), considers the diversity of perspectives he heard, while interjecting horrifying historical facts, noting the shocking rise in hate crimes throughout the US and across the globe in our current time, and posing the momentous question, “Is home still safe?” – and if it isn’t, where in the world is?

Weaving back and forth between 2016-17 and 1944-46, the personal story is presented through the device of a narrator (Patrick Solomon, performed by Richard Topol), a member of the contemporary family who revisits scenes, all set in Paris, in the home of his sister (Betsy Aidem in the pivotal role of Marcelle Solomon Benhamou) in the first year of Trump’s US presidency, and that of their great-grandparents during the Holocaust and post-WWII. The long family line is tied together not only by genealogy, but by their shared experience of bigotry, hatred, and fear, then and now, and the central issue of how best to deal with it – each with a different idea and level of devotion to their religion and roots, and to the family’s piano business, founded in 1855, and still being run by the 86-year-old Pierre (played by Pierre Epstein) – the only figure who spans the two eras.

A committed ensemble cast of eleven – Yair Ben-Dor, Francis Benhamou, Ari Brand, Peyton Lusk, Molly Ranson, Nancy Robinette, Jeff Seymour, and Kenneth Tigar, along with Topol, Aidem, and Epstein – captures the distinctive personalities, beliefs, and responses of the characters in the weighty drama, which is lightened by injecting humor into their adamant points of view and ongoing heated arguments. The familial debate is triggered by Molly, a distant cousin from NYC (embodied with spot-on timing and youthful ebullience by Ranson), who visits Marcelle’s home every weekend during her study abroad year in France and is more dedicated to the language and the great croissants she eats there than to her 25% Jewish heritage, and the arrival of Marcelle’s adult son Daniel (played with sensitivity by Ben-Dor), beaten and bloodied after being attacked on the street for being a Jew (identified by the yarmulke he wears, despite his mother’s repeated demands for him to take it off when outside, or to cover it with a cap).

When Daniel’s father and Marcelle’s husband Charles (the thoughtful Seymour) – a Sephardic transplant from Algeria, whose family fled in the ‘60s – admits to being scared of continuing to live amidst the burgeoning anti-Semitic assaults in France and his desire to relocate to Israel, what follows is a series of polemical confrontations on the need for survival, individual adherence to the traditions of Judaism, the value of assimilation, and the heartbreak of leaving one’s home to begin anew in an unfamiliar land, as has been the plight of the diaspora of the “wandering Jew” for millennia. The conflict among the family members is fueled by the non-stop manic tirades of Elodie (the bipolar daughter, in her late twenties, of Charles and Marcelle, fully embraced in an explosive performance by Benhamou), who spews her opinionated venom and insults at Molly, while angrily apprising her of the persecutions and terrorism of the past and present.

With a running time of three hours, the repeatedly expressed attitudes and volatile exchanges of the impassioned characters become redundant and could use some trimming, and they also leave us with the disheartening question of how diverse cultures and strangers can ever begin to get along (a leitmotif of “us versus them” rhetoric is voiced throughout the script), when members of a family can’t. In the end, the resolutions come too quickly and easily to be believable, in consideration of their strong-willed personalities, deeply committed stances, and tendency to do battle with one another, rather than to listen to each other.

The set, too (by Takeshi Kata), contributes to the length of the production, and often becomes a distraction, with its frequent rotations and repositioning of furniture between scenes (perhaps intended as a metaphor for the characters’ different outlooks). Costumes by Sarah Laux, and hair and makeup by J. Jared Janas, are suited to the personalities, and Amith Chandrashaker’s lighting, sound by Lee Kinney and Daniel Kluger, and original music by Kluger help set the shifting times and moods.

Though, for me, the play could be shortened and still make its point, Prayer for the French Republic leaves us with just that, not only for France but for the US and the rest of the world. It’s an ever-timely message that people everywhere should accept diversity and not force others to forsake their beliefs and identity to fit in, or be subjected to inconceivable hatred, violence, and fear.

Running Time: Three hours, including two intermissions.

Prayer for the French Republic plays through Sunday, March 27, 2022, at Manhattan Theatre Club, performing at New York City Center, Stage I, 131 West 55th Street, NYC. For tickets (starting at $99), call (212) 581-1212, or go online. Everyone must show proof of COVID-19 vaccination and a valid photo ID to enter the building and must wear a mask when inside.