“It’s really hard to tell people really true things.”

That line written by E.M. Lewis — in her play How the Light Gets In, now at 1st Stage — lands like a solemn memo to self. It is spoken first by a tough-looking but benevolent tattoo artist named Tommy Z, and it is repeated soon after by Kat Lane, a waif-like, homeless runaway. They have met, improbably, in an emergency room, where Tommy Z has brought his brother, who OD’ed on heroin, and where Kat has come with bloody forearms, having tried to kill herself. And in one of the play’s many moving moments of random kindness, they connect; their lives touch: Tommy Z offers to tattoo Kat’s arms to cover her scars.

Connecting through kindness could be the catchphrase for this exquisite production. And chance meetings between strangers whose truths are gently told could aptly describe its shape.

The play, directed by Alex Levy with acute sensitivity, takes place mostly in a gorgeous Japanese garden (designed by Kathryn Kawecki and lit by Helen Garcia-Alton with affectionate attention to detail). The contours of its curving greenscape seem to mirror nature, lanterns along the flagstone path and boardwalk light up in different colors, birds chirp cheerily (sound design is by Gordon Nimmo-Smith), hanging lengths of rope emulate a tree, and a wooden bridge spans a serpentine pond that lacks for verisimilitude only koi fish. (The set is built above a pool of water.) The place seems so perfectly peaceful that personal troubles might for a while be forgotten.

That well may be the reason Grace Wheeler comes here. A woman middle-aged but by no means matronly, Grace is a travel writer who never travels — she composes from research and her imagination instead — and she volunteers as a docent leading tours of the Japanese garden. Early in the play, we learn she is expecting the result of a breast biopsy — which she receives in a phone call that wordlessly desolates her. Tonya Beckman’s performance as Grace, rich in nuance and intuition, is especially eloquent in such silent, textless instants.

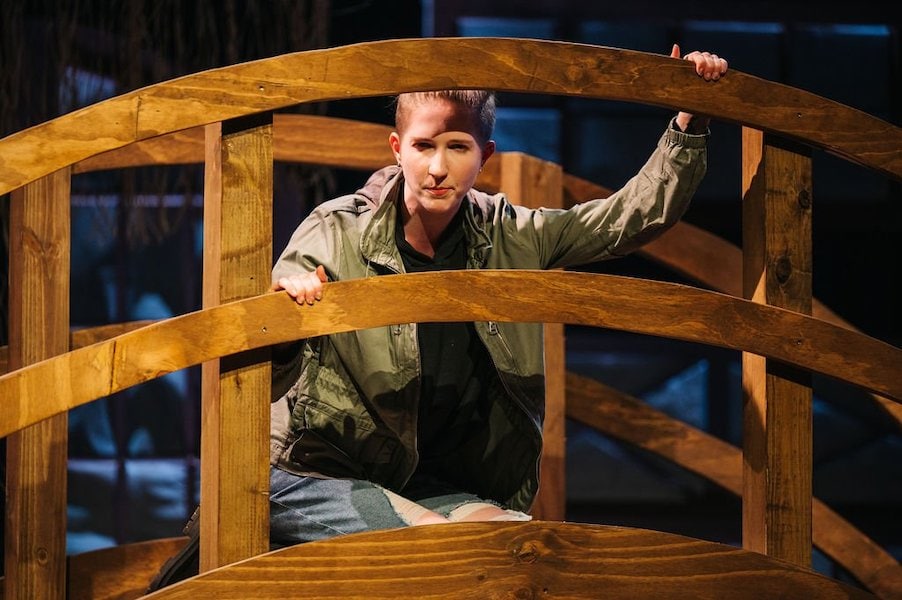

Kat happens to overhear when Grace gets the distressing call. Kat has been living in the garden for the last two months under a willow tree because her home is not safe (familial abuse is implied). And in the wonderful way that Lewis interweaves the lives of disparately hurting characters, Kat and Grace strike up a conversation that turns into a connection between a caring grownup and an otherwise lost youth. Superb in the role, Madeleine Regina conveys Kat’s chipper optimism despite the world of woe she’s run from.

Kat and the tattoo artist Tommy Z at times narrate what’s going on in the play’s intersecting stories. The device not only works economically to keep us up to speed on exposition but allows us fascinating entry into who everyone is becoming now that their paths are crossing. Joel Ashur as Tommy Z is particularly impactful in this narrator role. By outward appearances — gleaming jewelry pierces his earlobe and septum — he’s not someone a garden variety visitor might warm to on sight, but Ashur brings out the character’s heart of gold with a stature and gravitas that impress throughout the play.

There’s a fourth character who comes to the garden, an architect named Haruki Sakamoto, acclaimed in his native Japan, who has been commissioned to design a tea house for the place. But he’s stumped — nothing he has come up with can surpass the simple beauty that’s already there. Daily he arrives and meticulously sketches on his pad then keeps tearing out pages, fussily crumpling them, and tossing them to the ground (which is of course the frustrated-creator cliche, but it does get distracting as the literal litter accumulates on what’s ostensibly a pristine park).

Central among the accidental meetings in this play is the tenderly tentative connection that develops between Haruki and Grace — an improbable love story that is really the heart of the play. And Jacob Yeh’s persuasive performance as Haruki becomes particularly poignant as he expresses both his own growing fondness for Grace and his emotional reserve since he lost his wife ten years ago:

HARUKI: It is better to be alone than to allow your heart to be ripped out of your chest again. This is what I have thought for a long time.

GRACE: Is that what you still think?

HARUKI: It is hard to be without when you know what it’s like to be with.

Grace has her own reason for reluctance, an aversion to being seen naked that will resonate with anyone who’s faced breast cancer. (There is a boldly graphic scene of Grace’s radiation treatment effected solely by Garcia-Alton’s harsh lights, Nimmo-Smith’s severe electronic sound, and Beckman’s visceral performance.)

Thus the classic question “Will they or won’t they?” comes to hover warmly over a play whose title comes from a lyric of Leonard Cohen’s:

Ring the bells that still can ringForget your perfect offeringThere is a crack, a crack in everythingThat’s how the light gets in

The line is referenced in the play when Tommy Z tells Kat about a time he tattooed over the scars of a burn victim still so traumatized by the fire he could not speak. Eventually, the man began to open up. Reflecting on that memory, Tommy says to Kat:

TOMMY Z: Sometimes I think the whole job is trying to put in windows where there used to be walls, so the light can get in.

On the wall far upstage, backgrounding the lovely Japanese garden, is an expansive assemblage of window frames — as if waiting to let in light the way this beautiful play does.

Running Time: Approximately 90 minutes with no intermission.

EXTENDED: How the Light Gets In plays through March 26, 2023 (Thursdays at 7:30 pm, Fridays at 8 pm, Saturdays at 2 pm and 8 pm, and Sundays at 2 pm), at 1st Stage, 1524 Spring Hill Road, Tysons, VA. Getting there. To purchase tickets ($15, student, military, educators; $47, seniors; $50, general admission; $35, Thursday evening), go online or call 703-854-1856. The first 20 tickets for each performance are only $20. Plus, a YES pass for high school students in Fairfax County offers free subscriptions. See details here.

The program for How the Light Gets In is online here.

Open-Captioned Performances: March 9 at 7:30 pm, March 10 at 8 pm, March 11 at 2 pm and 8 pm, March 12 at 2 pm

Audio-Described Performance: March 12 at 2 pm

COVID Safety: All patrons, volunteers, and staff are required to be masked while inside the 1st Stage Theatre facility. See 1st Stage’s complete COVID Safety Information here.

How the Light Gets In

Written by E.M. Lewis

Directed by Alex Levy

FEATURING

Tommy Z: Joel Ashur

Grace Wheeler: Tonya Beckman

Kat Lane: Madeleine Regina

Haruki Sakamoto: Jacob Yeh

PRODUCTION & DESIGN

Set design by Kathryn Kawecki, lighting design by Helen Garcia-Alton, costume design by Debra Kim Sivigny, props design by Cindy Landrum Jacobs, sound design by Gordon Nimmo-Smith. Intimacy coach: Lorraine Ressegger, stage manager: Rebecca Talisman, associate artistic director: Deidra Lawan Starnes, assistant sound design: Alistair Edwards.

SEE ALSO: Playwright E.M. Lewis on how ‘How the Light Gets In’ happened (interview by Bob Bartlett, March 3, 2023)