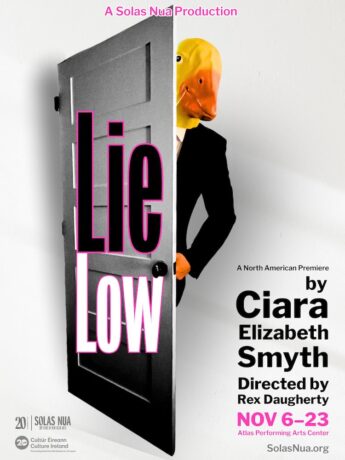

Sometimes, self-awareness can be a kind of prison. That’s a dilemma encountered by Faye, the protagonist of Ciara Elizabeth Smyth’s play Lie Low, now making its North American premiere at Washington, DC’s Solas Nua. Faye (Megan Graves) is a survivor of sexual assault; after a party, a man wearing a duck mask broke into her house, hit her, took off her “knickers,” and revealed his penis. A year later, Faye has become an insomniac and receives little help from her doctor. When her brother Naoise (Cody Nickell) arrives at her place, Faye has a hidden agenda: she wants Naoise to roleplay as her assaulter as a kind of “exposure therapy,” to face her greatest fear.

Throughout Lie Low, Faye is painfully self-aware of her own situation. “Moment to moment, really, I feel good,” she tells her brother. “It’s just because someone broke in once, my brain seems to think it’s rational for that to happen again… And no matter how many times someone says it’s not going to happen, I don’t believe them.”

When I read the Lie Low script, those lines felt painfully true to my own struggles with mental health (even though I don’t have the same experiences as Faye). It might be easier for Faye and me if irrational thoughts completely remade our realities. Instead, we’re trapped in a frustrating limbo where we can acknowledge thoughts are paranoid or delusional — but that doesn’t stop those thoughts from arriving anyway.

I spoke to Smyth on a recent Zoom call and shared my identification with those lines. The Irish playwright said many audiences have a similar reaction. “It’s been quite resonant with people — the intellectual fighting, the emotional and physical going, ‘Look, I know this isn’t rational. However, knowing it’s not rational doesn’t make me feel better,’ ” she said. “Obviously, this is an extreme of that, because that can happen across the board.”

Extreme is the right word to use for Lie Low, a provocative show that interrogates a rape culture that both creates sexual assault and fails its survivors. Faye and Naoise may have wanted to “lie low” after intense times in their lives, but Smyth continually raises the stakes for both characters. Naoise also has a hidden agenda for seeing his sister, so the two interrogate each other on their intertwined histories. Smyth intersperses their dialogue scenes with swing dances between Faye and a masked “Duckman,” which often feel like surreal fever dreams of traumatic events.

Lie Low has had a long journey to DC. The show premiered at the Dublin Fringe Festival in 2022, self-produced by Smyth under a “profit share” model in which production members received a percentage of the production’s profits. In 2023, the show transferred to the Abbey Theatre in Dublin and the Traverse Theatre in Edinburgh, and in 2024, it premiered at London’s Royal Court Theatre. Lie Low has since been produced worldwide, having been translated into Italian, Turkish, and Chinese. Director Tom Creed is even adapting Smyth’s script into an opera.

Lie Low has undergone an incredible transformation from Smyth’s roots making scrappy, D.I.Y. theater. Yet Solas Nua, a 20-year-old DC theater company dedicated to contemporary Irish arts, has engaged with Smyth since Lie Low’s first public performances. Solas Nua’s artistic director, Rex Daugherty, saw the show at the Dublin Fringe Festival and has continued to stage Smyth’s work since, including DC-staged readings of Smyth’s plays Irishtown in 2023 and Sauce in 2024. Daugherty produces and directs this current Lie Low production.

With Irishtown having its world premiere production at New York City’s Irish Repertory Theatre earlier this year, American audiences are becoming more familiar with Smyth’s unique voice: metatheatrical and confrontational, while still humorous and idiosyncratic. Lie Low feels specific to Ireland, but its arguments can feel elemental. The show’s systemic critiques and uncompromising standoff now feel freshly relevant when staged in DC’s tense political climate.

Still, Lie Low is a deeply personal work for Smyth. In a 2024 post-show talkback for the Royal Court production, Smyth candidly shared that the play was inspired by multiple events in her life. This included experiences with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following an assault that happened a decade prior to the diagnosis, as well as her involvement in publicly speaking about the inappropriate behavior and bullying she experienced while working at the Dublin Gate Theatre.

Since the Solas Nua production marks North America’s first encounter with Smyth’s most famous play, I was eager to talk to the Irish playwright about her layered and sometimes divisive work. I spoke virtually with Smyth about Lie Low’s intriguing images, the repetition of trauma, and how writers can explore intense subject matters. (Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.)

I know Rex Daugherty saw the first production of Lie Low. What made you decide to approve this Solas Nua production?

Ciara Elizabeth Smyth: What I was really thrilled by was Rex’s support and commitment to building a relationship over a number of years… It feels like Lie Low is the right show for the company, but also the right show for Rex. He’s a really physical director. He’s really clever, he’s very funny. It felt like we were on the same page. Look, I was just delighted that they were interested in it, because [Lie Low] is not a “walk in the park” in some ways. It can be strange and uncomfortable.

When I read the Lie Low script, I appreciated its detailed images. There are references to Rice Krispies and ducks. One of my favorite lines is when Faye’s doctor tells her that depression creeps in, and “Next thing you know, you’re using your finger to eat expired caviar in a public toilet.” I know there’s a lot of consideration that goes into writing something so specific, even if it feels random. How did you balance the specific and surreal language?

I’m really interested in finding the right form for the content, the right form for this story, and how the two speak to each other. Something about the nature of this — the nature of insomnia or post-traumatic stress disorder after sexual assault — felt highly descriptive verbally, but then had this other ethereal element that felt like it could only be expressed through physical, absurd punctuation. So the play oscillates between two people in a room having a conversation, and then these periods that feel quite surreal, or they feel like they’re trying to express something in a more physical, visceral way.

And I suppose those images that you’re thinking about, a lot of them are related to food — which is purposeful because of the psychological state that the main character is in. Her relationship to her body, and her image, and how she is nourishing her body, has completely changed. But they’re also quite grotesque as well. So the food is almost used as an avenue into something sort of disgusting [laughs], which I found very interesting in tandem with what the protagonist is going through.

Comedy is something that you’re employing as a playwright, but comedy is something that Faye is using, too. She can be purposefully comedic, telling her brother, “And if you hit me a bit, it’s OK.” She’s in on the joke. But Faye later critiques her brother for hiding his cruelty behind irony. How do you think Faye feels about comedy?

I think nothing is completely bereft of comedy. And I think [Faye] is using comedy as a coping mechanism, or at least a sort of humor or humor-adjacent language as a way to cope. I also think she’s not fully cognizant of the pain and the damage that has been done to her. She has a very clear goal in this [play], however short-sighted or mechanical it seems. She’s really trying to cope with something that is not tangible and has no timeline, and that is devastating to her.

I feel like both characters cycle through different tactics to get what they want. They are having a rekindling moment in some ways. And in other ways, they’re quite goal-oriented. I think the information that comes out within the play changes Faye, and her relationship to humor at that point changes as well, or at least that was my intention.

That also makes me think about who the audience roots for within the story. Initially, they might be on Naoise’s side, thinking, “Faye has a lot going on mentally.” But as new information gets shared, audiences might sympathize more with Faye. Do you think about who an audience roots for in a particular moment? Do audiences need to root for one person?

My aim in writing this was to create something where the audience felt like their allegiances were switching. I really wanted to leave room for divisiveness and disagreement in who the audience was rooting for. It’s not a clear situation, and I think that’s probably far closer to real life than a cut-and-dry “This is the hero and this is a villain.”

I think they’re both wrong in some ways, and they’re both right in other ways. And I was really interested in the damage that is caused after something like a sexual assault. It can be one event, but it has an insidious nature that repeats itself on the victim, and it changes their behavior, and the way they look at things, and their perspective, and the damage that’s left behind. If that’s not dealt with, that can go on to damage other people. I’m very keen for audiences to have their own opinion. I’m certainly not trying to give any answers or proselytize with the play.

You say that trauma has a repetitive quality, and so does this show. Faye needs her brother to roleplay as her assaulter not just once, but over and over again. The play’s repetition made me feel like I was in Faye’s mind. There were moments during the roleplay scenes when I felt a sense of danger, asking myself, “Is this real? Is this not real? Is this still safe roleplay, or is Faye unsafe?” I questioned the reality of what I was experiencing. Why was it important for you to place audiences in that position?

What felt really honest to me about that — the ramifications of an assault or experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder, which I have some experience with — was the repetition of it. For a long time, you would be put back in that situation where danger was not possible, but probable. There’s a cyclical nature to those thoughts in your head, and rationale goes out the window because it doesn’t matter anymore, because it started to become physical as opposed to intellectual. So repetition was really important for me in this. I suppose there’s a tragedy to Faye doing her best to repeat something that has been so painful to her, in a way to be better.

Another thing that felt equally authentic but inherently dramatic was the slippiness of reality. I personally have experience with things like panic attacks and auditory hallucinations as a result of PTSD. So the question of “What’s real? What’s gonna happen?” — that certainly was my aim to put the audience in that position. I think it’s a fascinating way to mirror the protagonist’s emotional journey.

Within the script, Faye says that exposure therapy is when “you expose yourself to your fear in a safe environment and it helps you get over it.” A lot of people might assume that’s what theater can be: a safe environment where you’re exposed to fear. But many people who work in theater might also say, “Theater is not a safe environment all the time.” Do you think theater can be a form of exposure therapy?

As I said earlier, I think theater is for an audience. So my North Star when writing something is trying to think about the audience — not necessarily trying to anticipate their reaction, but I’m interested in things being funny and subversive, and unpredictable and entertaining. So I don’t feel, for me, that there’s any space for therapy in there. It just doesn’t feel like the right place for me to come from. And I think it would be the worst therapy ever! [Laughs] I think it would be the most traumatizing version of therapy that you could possibly choose, I mean that would be horrific!

I was very lucky in the writing of this. There are a lot of spectacular actors in Ireland where I’m from, and I had the pleasure of being able to write it for two actors [Michael Patrick and Charlotte McCurry] that I know very well and that I adore… So I think it was really as carefully [staged] as possible, because we didn’t really have any money. We had some development funding for a two-day workshop. So when it premiered in Dublin, we were all working for a profit share, and stressed out of our minds, and hadn’t been paid in weeks. I think as much as possible, I was really trying to carefully hone [Lie Low] and put a dilemma or a question on stage that I hadn’t seen before, or that I hadn’t seen done in this form before.

Do you have feelings about Lie Low that you didn’t have a few years ago? Or have you felt your relationship to the writing change?

Absolutely. When it first went on, I found it incredibly difficult to watch, and I feel like that about everything I write. When it first goes on, you don’t really know what it is until you put it in front of an audience, and then you’re all discovering what it is together. I don’t enjoy my first production, usually. I don’t think that’s a bad thing. It’s hard!

With everything that you do, there’s some good and there’s some bad, but the reaction to [Lie Low] was so positive. We were invited over to Edinburgh, and then we were invited to London, and the play’s been translated into multiple languages. There is actually a production in Istanbul at the moment. I think that has allowed me to relinquish some tension that I had about the play. The more it’s been on, the more I’ve been able to approach it with an element of dispassion. And I don’t mean that in a negative way; I mean that in a really positive way, that I’m able to look, but it’s a little bit cooler now.

You’ve spoken about how this play was inspired by experiences from your own life, although it’s not strictly autobiographical. A lot of writers face a dilemma while writing, asking themselves, “How can I write about intense subjects that touch on my life, while also still taking care of myself, and working as an artist to create something separate from me?” Do you have any advice for writers who want to balance those different impulses?

I think it’s very difficult to take care of yourself when you’re writing or making things that feel this intense or this intensely personal. A lot of my time was spent — in the first iteration of this and the premiere in Dublin — trying to take care of the cast, and I think that’s a consequence of not really having any budget. I think it’s really difficult to take care of yourself when there’s no money on the table, and a lot of your time is spent cutting breathing holes in plastic duck masks at night.

The only advice I would really have for any writer is to keep writing as much as physically possible, and show people what you’re writing — especially if it’s theater. You need to hear it out loud. All I’m really trying to do, as I said, is write for an audience, and write something honest. Hopefully, I’ve been successful in at least one of those things. But taking care of yourself, I think, is something I’m still learning to do. I don’t think it’s built into a lot of industries, or a lot of roles.

I definitely believe taking care of other people is a helpful part of a creative process. That’s something that I’ll be carrying into the future.

I think that was a way for me to feel like I had some modicum of control — in a piece and a process that felt very out of control — trying to make sure that the actors and the team were as supported as possible, and that there was an intimacy coordinator, and that we were listening. The actors could stop, or talk, or do whatever they needed to do. I think at the time, that was probably the best use of my time and energy.

Running Time: 65 minutes.

Lie Low plays through November 23, 2025, presented by Solas Nua, performing at Atlas Performing Arts Center, 1333 H St NE, Washington, DC. Showtimes are Thursdays-Fridays at 7:30 p.m. and Saturdays-Sundays at 2:30 p.m. and 7:30 p.m. Tickets ($45–$60 with pay-what-you-can options available throughout the run) are available online and through TodayTix.

The digital program for Lie Low is here.

The North American Premiere of

Lie Low

Written by Ciara Elizabeth Smyth

Directed by Rex Daugherty

SEE ALSO:

A hilarious replay of vulnerability to sexual assault in ‘Lie Low’ from Solas Nua (review by John Stoltenberg, November 9, 2025)